正在加载图片...

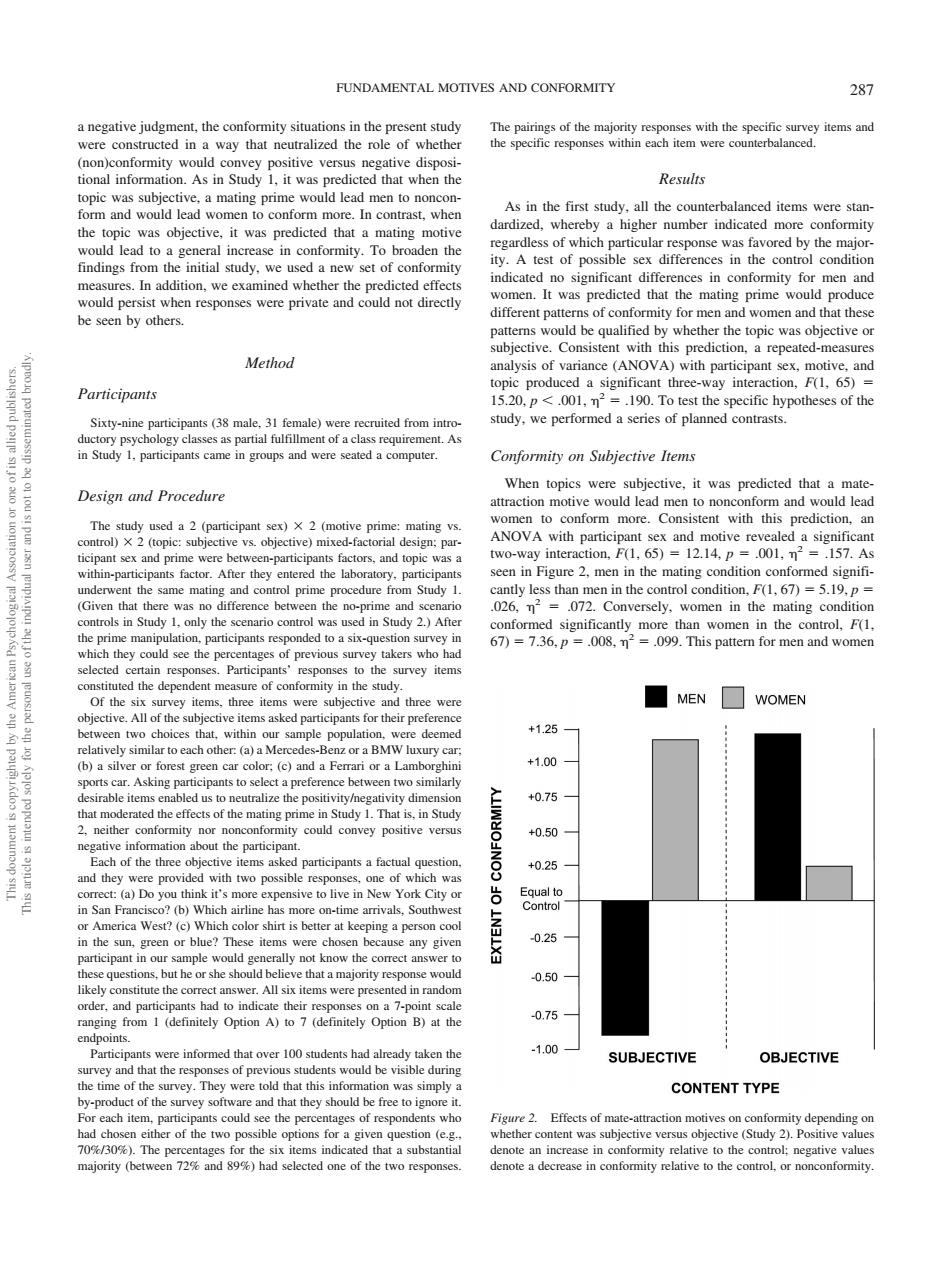

FUNDAMENTAL MOTIVES AND CONFORMITY 287 non)conf rmity would e would lead men to en tn Results As in the first study,all the counterbalanced items were stan inc Method Participants 15.20..To test the specific hypotheses of the (male.3 female) recruited from intr tudy.we performed a series of planned contrasts Conformity on Subjective Items When Design and procedure topics were predicted that a mte onform more.Co sistent with this prediction.an and After the in Figure 2.men in the mating conditio e a see t items subiective an thre ■MEN☐WOMEN 1.25 r:(c)and a Ferrari or a L e里a 05 mity cou convey 050 of th d participants +0.25 (a)Do you think it's pensive to live in New York City o 025 yntk ow the com 0.50 ems were p 0.75 .1.00 SUBJECTIVE OBJECTIVE CONTENT TYPE the perce of respon a negative judgment, the conformity situations in the present study were constructed in a way that neutralized the role of whether (non)conformity would convey positive versus negative dispositional information. As in Study 1, it was predicted that when the topic was subjective, a mating prime would lead men to nonconform and would lead women to conform more. In contrast, when the topic was objective, it was predicted that a mating motive would lead to a general increase in conformity. To broaden the findings from the initial study, we used a new set of conformity measures. In addition, we examined whether the predicted effects would persist when responses were private and could not directly be seen by others. Method Participants Sixty-nine participants (38 male, 31 female) were recruited from introductory psychology classes as partial fulfillment of a class requirement. As in Study 1, participants came in groups and were seated a computer. Design and Procedure The study used a 2 (participant sex) 2 (motive prime: mating vs. control) 2 (topic: subjective vs. objective) mixed-factorial design; participant sex and prime were between-participants factors, and topic was a within-participants factor. After they entered the laboratory, participants underwent the same mating and control prime procedure from Study 1. (Given that there was no difference between the no-prime and scenario controls in Study 1, only the scenario control was used in Study 2.) After the prime manipulation, participants responded to a six-question survey in which they could see the percentages of previous survey takers who had selected certain responses. Participants’ responses to the survey items constituted the dependent measure of conformity in the study. Of the six survey items, three items were subjective and three were objective. All of the subjective items asked participants for their preference between two choices that, within our sample population, were deemed relatively similar to each other: (a) a Mercedes-Benz or a BMW luxury car; (b) a silver or forest green car color; (c) and a Ferrari or a Lamborghini sports car. Asking participants to select a preference between two similarly desirable items enabled us to neutralize the positivity/negativity dimension that moderated the effects of the mating prime in Study 1. That is, in Study 2, neither conformity nor nonconformity could convey positive versus negative information about the participant. Each of the three objective items asked participants a factual question, and they were provided with two possible responses, one of which was correct: (a) Do you think it’s more expensive to live in New York City or in San Francisco? (b) Which airline has more on-time arrivals, Southwest or America West? (c) Which color shirt is better at keeping a person cool in the sun, green or blue? These items were chosen because any given participant in our sample would generally not know the correct answer to these questions, but he or she should believe that a majority response would likely constitute the correct answer. All six items were presented in random order, and participants had to indicate their responses on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely Option A) to 7 (definitely Option B) at the endpoints. Participants were informed that over 100 students had already taken the survey and that the responses of previous students would be visible during the time of the survey. They were told that this information was simply a by-product of the survey software and that they should be free to ignore it. For each item, participants could see the percentages of respondents who had chosen either of the two possible options for a given question (e.g., 70%/30%). The percentages for the six items indicated that a substantial majority (between 72% and 89%) had selected one of the two responses. The pairings of the majority responses with the specific survey items and the specific responses within each item were counterbalanced. Results As in the first study, all the counterbalanced items were standardized, whereby a higher number indicated more conformity regardless of which particular response was favored by the majority. A test of possible sex differences in the control condition indicated no significant differences in conformity for men and women. It was predicted that the mating prime would produce different patterns of conformity for men and women and that these patterns would be qualified by whether the topic was objective or subjective. Consistent with this prediction, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with participant sex, motive, and topic produced a significant three-way interaction, F(1, 65) 15.20, p .001, 2 .190. To test the specific hypotheses of the study, we performed a series of planned contrasts. Conformity on Subjective Items When topics were subjective, it was predicted that a mateattraction motive would lead men to nonconform and would lead women to conform more. Consistent with this prediction, an ANOVA with participant sex and motive revealed a significant two-way interaction, F(1, 65) 12.14, p .001, 2 .157. As seen in Figure 2, men in the mating condition conformed significantly less than men in the control condition, F(1, 67) 5.19, p .026, 2 .072. Conversely, women in the mating condition conformed significantly more than women in the control, F(1, 67) 7.36, p .008, 2 .099. This pattern for men and women Figure 2. Effects of mate-attraction motives on conformity depending on whether content was subjective versus objective (Study 2). Positive values denote an increase in conformity relative to the control; negative values denote a decrease in conformity relative to the control, or nonconformity. FUNDAMENTAL MOTIVES AND CONFORMITY 287 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.���