正在加载图片...

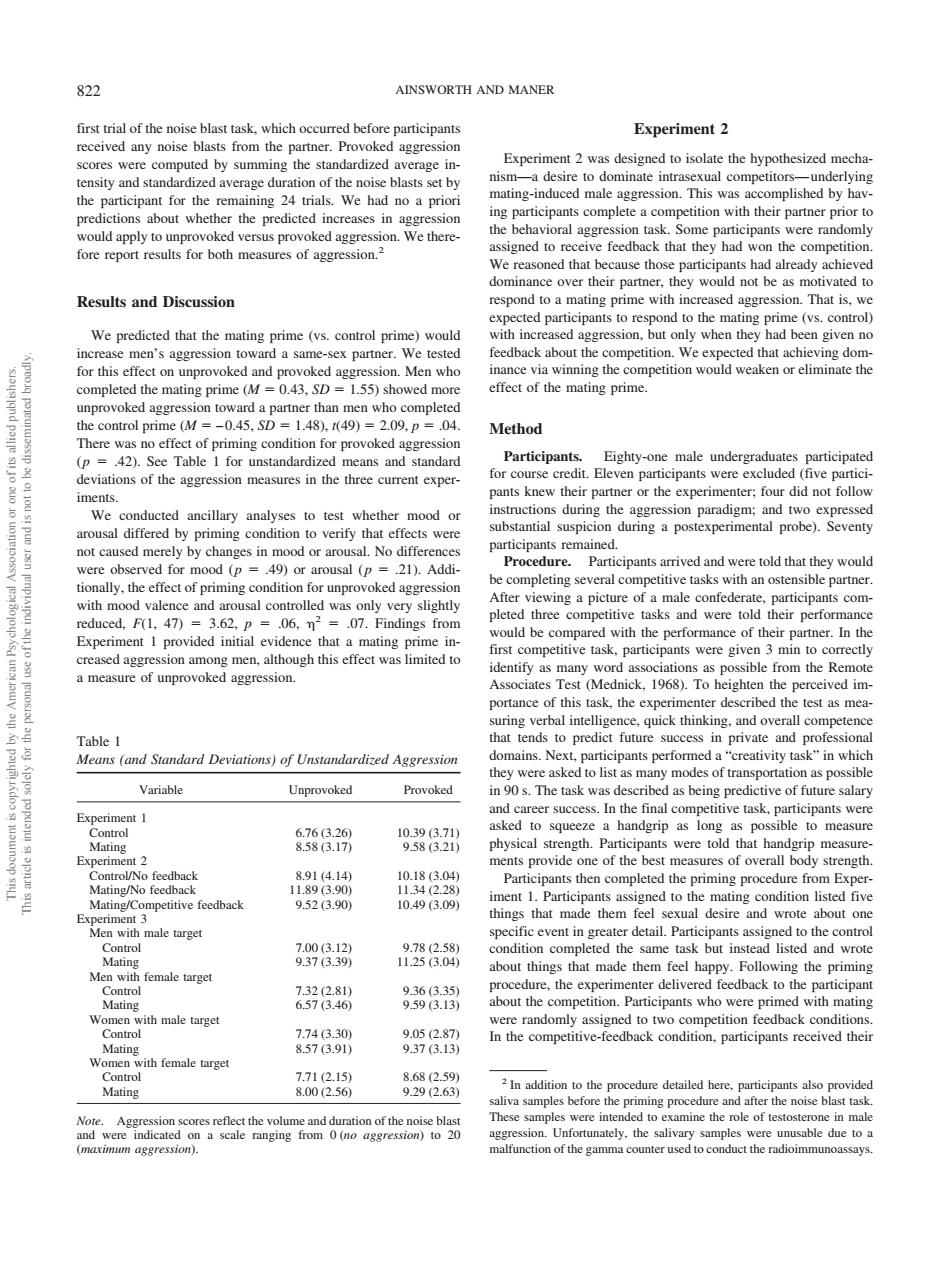

822 AINSWORTH AND MANER blast task which before participant Experiment 2 scores were uted by summing the standardized average in. xpe ardized a blasts set by task e feed k that they ore report results measures of aggress e over their partner,they would not be as motivated t Results and Discussion o a ma ng pnme with S.W We predicted that the ( with inc nsgg nance effect of the mating prime d aggre no effect of priming condition for provoked ag Method There w 42 Participants. male under or c ments ancillary analyses to test mood or antial suspicio during a postexperimental probe).Seventy ot caused merely by changes in mood or arousal no differ ved for arousal (P Procedure. ,49) 21.Ad Participants arrived and were told that they would th an os and sal controlled was only very slightly ted three ed.F(1.47) 36206,n=0. ndings ld be ion among men.although this effect was limited to measure of unprovoked aggression. the Remote ce of this task the experimenter described the test as mea 6e (and Standard Deviations)of Unstandardized Aggression Nex s of tra as po Unprovoked Provoked s.In the final compe ng ve task. pticipantswer 8689 1988出 s provid ne of the best measures of overall 10.496.09 ssigned to the mti onditi listed fiv npetitive feedback t 3 剧 ndition completed the same task but inst listed and wrot ving the female target 868 vere primed with mating 882 on. ct the radioimmunoassays first trial of the noise blast task, which occurred before participants received any noise blasts from the partner. Provoked aggression scores were computed by summing the standardized average intensity and standardized average duration of the noise blasts set by the participant for the remaining 24 trials. We had no a priori predictions about whether the predicted increases in aggression would apply to unprovoked versus provoked aggression. We therefore report results for both measures of aggression.2 Results and Discussion We predicted that the mating prime (vs. control prime) would increase men’s aggression toward a same-sex partner. We tested for this effect on unprovoked and provoked aggression. Men who completed the mating prime (M 0.43, SD 1.55) showed more unprovoked aggression toward a partner than men who completed the control prime (M – 0.45, SD 1.48), t(49) 2.09, p .04. There was no effect of priming condition for provoked aggression (p .42). See Table 1 for unstandardized means and standard deviations of the aggression measures in the three current experiments. We conducted ancillary analyses to test whether mood or arousal differed by priming condition to verify that effects were not caused merely by changes in mood or arousal. No differences were observed for mood (p .49) or arousal (p .21). Additionally, the effect of priming condition for unprovoked aggression with mood valence and arousal controlled was only very slightly reduced, F(1, 47) 3.62, p .06, 2 .07. Findings from Experiment 1 provided initial evidence that a mating prime increased aggression among men, although this effect was limited to a measure of unprovoked aggression. Experiment 2 Experiment 2 was designed to isolate the hypothesized mechanism—a desire to dominate intrasexual competitors— underlying mating-induced male aggression. This was accomplished by having participants complete a competition with their partner prior to the behavioral aggression task. Some participants were randomly assigned to receive feedback that they had won the competition. We reasoned that because those participants had already achieved dominance over their partner, they would not be as motivated to respond to a mating prime with increased aggression. That is, we expected participants to respond to the mating prime (vs. control) with increased aggression, but only when they had been given no feedback about the competition. We expected that achieving dominance via winning the competition would weaken or eliminate the effect of the mating prime. Method Participants. Eighty-one male undergraduates participated for course credit. Eleven participants were excluded (five participants knew their partner or the experimenter; four did not follow instructions during the aggression paradigm; and two expressed substantial suspicion during a postexperimental probe). Seventy participants remained. Procedure. Participants arrived and were told that they would be completing several competitive tasks with an ostensible partner. After viewing a picture of a male confederate, participants completed three competitive tasks and were told their performance would be compared with the performance of their partner. In the first competitive task, participants were given 3 min to correctly identify as many word associations as possible from the Remote Associates Test (Mednick, 1968). To heighten the perceived importance of this task, the experimenter described the test as measuring verbal intelligence, quick thinking, and overall competence that tends to predict future success in private and professional domains. Next, participants performed a “creativity task” in which they were asked to list as many modes of transportation as possible in 90 s. The task was described as being predictive of future salary and career success. In the final competitive task, participants were asked to squeeze a handgrip as long as possible to measure physical strength. Participants were told that handgrip measurements provide one of the best measures of overall body strength. Participants then completed the priming procedure from Experiment 1. Participants assigned to the mating condition listed five things that made them feel sexual desire and wrote about one specific event in greater detail. Participants assigned to the control condition completed the same task but instead listed and wrote about things that made them feel happy. Following the priming procedure, the experimenter delivered feedback to the participant about the competition. Participants who were primed with mating were randomly assigned to two competition feedback conditions. In the competitive-feedback condition, participants received their 2 In addition to the procedure detailed here, participants also provided saliva samples before the priming procedure and after the noise blast task. These samples were intended to examine the role of testosterone in male aggression. Unfortunately, the salivary samples were unusable due to a malfunction of the gamma counter used to conduct the radioimmunoassays. Table 1 Means (and Standard Deviations) of Unstandardized Aggression Variable Unprovoked Provoked Experiment 1 Control 6.76 (3.26) 10.39 (3.71) Mating 8.58 (3.17) 9.58 (3.21) Experiment 2 Control/No feedback 8.91 (4.14) 10.18 (3.04) Mating/No feedback 11.89 (3.90) 11.34 (2.28) Mating/Competitive feedback 9.52 (3.90) 10.49 (3.09) Experiment 3 Men with male target Control 7.00 (3.12) 9.78 (2.58) Mating 9.37 (3.39) 11.25 (3.04) Men with female target Control 7.32 (2.81) 9.36 (3.35) Mating 6.57 (3.46) 9.59 (3.13) Women with male target Control 7.74 (3.30) 9.05 (2.87) Mating 8.57 (3.91) 9.37 (3.13) Women with female target Control 7.71 (2.15) 8.68 (2.59) Mating 8.00 (2.56) 9.29 (2.63) Note. Aggression scores reflect the volume and duration of the noise blast and were indicated on a scale ranging from 0 (no aggression) to 20 (maximum aggression). 822 AINSWORTH AND MANER This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.�