正在加载图片...

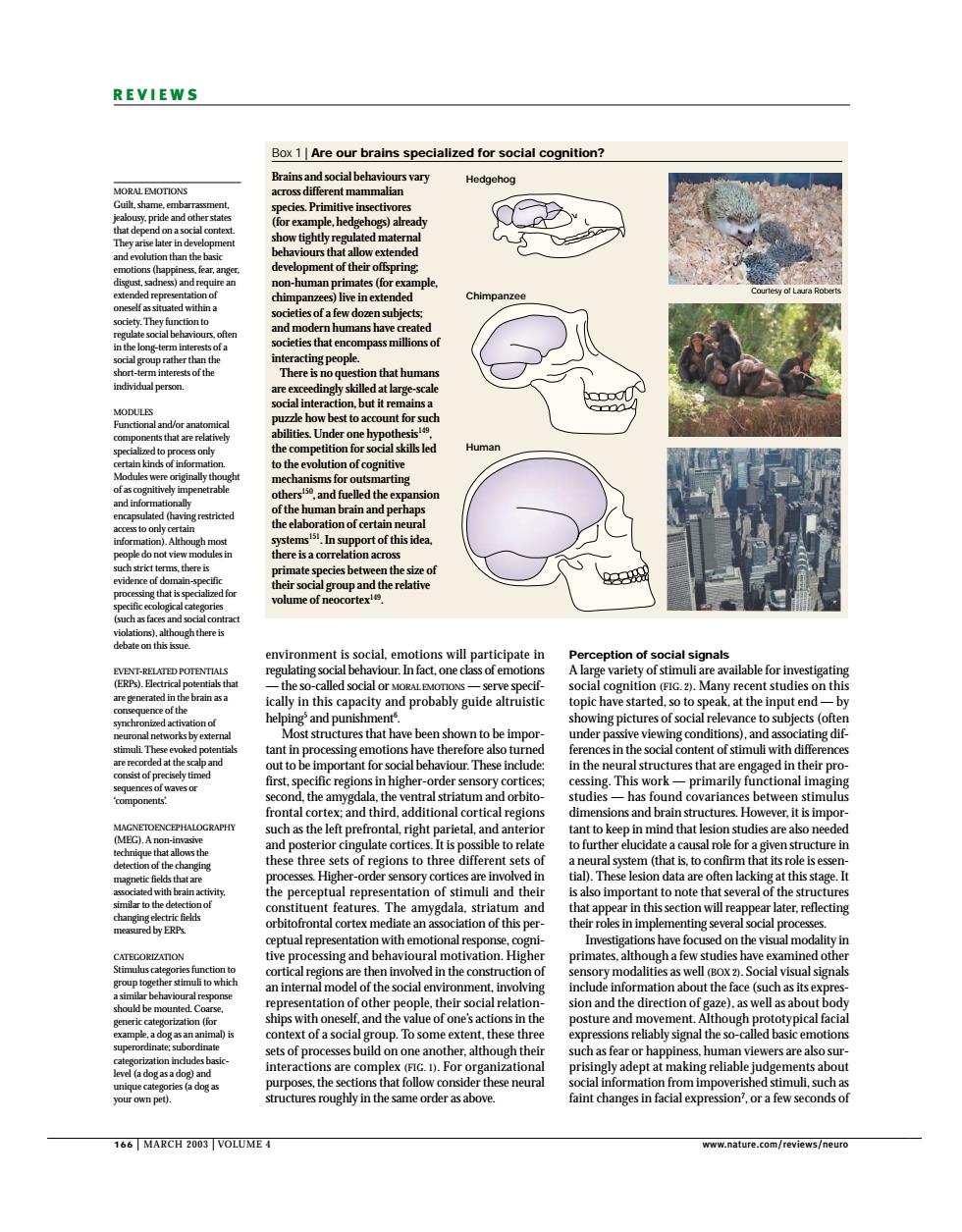

REVIEWS ox1 Are our brains specialized for social cognitior Hedgehog nd probably guide altruisti the left pre ntal nd a is to t diffe he r tation o timuli and the e th ral o the st ral motivation d in the c and the ohe and es nte are ngly adept ing reliab ures roughly in the same order as abov aint changes in facial expression',or a few seconds o 166 MARCH20O3 VOLUM正 MORAL EMOTIONS Guilt, shame, embarrassment, jealousy, pride and other states that depend on a social context. They arise later in development and evolution than the basic emotions (happiness, fear, anger, disgust, sadness) and require an extended representation of oneself as situated within a society. They function to regulate social behaviours, often in the long-term interests of a social group rather than the short-term interests of the individual person. MODULES Functional and/or anatomical components that are relatively specialized to process only certain kinds of information. Modules were originally thought of as cognitively impenetrable and informationally encapsulated (having restricted access to only certain information). Although most people do not view modules in such strict terms, there is evidence of domain-specific processing that is specialized for specific ecological categories (such as faces and social contract violations), although there is debate on this issue. EVENT-RELATED POTENTIALS (ERPs). Electrical potentials that are generated in the brain as a consequence of the synchronized activation of neuronal networks by external stimuli. These evoked potentials are recorded at the scalp and consist of precisely timed sequences of waves or ‘components’. MAGNETOENCEPHALOGRAPHY (MEG). A non-invasive technique that allows the detection of the changing magnetic fields that are associated with brain activity, similar to the detection of changing electric fields measured by ERPs. CATEGORIZATION Stimulus categories function to group together stimuli to which a similar behavioural response should be mounted. Coarse, generic categorization (for example, a dog as an animal) is superordinate; subordinate categorization includes basiclevel (a dog as a dog) and unique categories (a dog as your own pet). 166 | MARCH 2003 | VOLUME 4 www.nature.com/reviews/neuro REVIEWS Perception of social signals A large variety of stimuli are available for investigating social cognition (FIG. 2). Many recent studies on this topic have started, so to speak, at the input end — by showing pictures of social relevance to subjects (often under passive viewing conditions), and associating differences in the social content of stimuli with differences in the neural structures that are engaged in their processing. This work — primarily functional imaging studies — has found covariances between stimulus dimensions and brain structures. However, it is important to keep in mind that lesion studies are also needed to further elucidate a causal role for a given structure in a neural system (that is, to confirm that its role is essential). These lesion data are often lacking at this stage. It is also important to note that several of the structures that appear in this section will reappear later, reflecting their roles in implementing several social processes. Investigations have focused on the visual modality in primates, although a few studies have examined other sensory modalities as well (BOX 2). Social visual signals include information about the face (such as its expression and the direction of gaze), as well as about body posture and movement. Although prototypical facial expressions reliably signal the so-called basic emotions such as fear or happiness, human viewers are also surprisingly adept at making reliable judgements about social information from impoverished stimuli, such as faint changes in facial expression7 , or a few seconds of environment is social, emotions will participate in regulating social behaviour. In fact, one class of emotions — the so-called social or MORAL EMOTIONS — serve specifically in this capacity and probably guide altruistic helping5 and punishment6 . Most structures that have been shown to be important in processing emotions have therefore also turned out to be important for social behaviour. These include: first, specific regions in higher-order sensory cortices; second, the amygdala, the ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex; and third, additional cortical regions such as the left prefrontal, right parietal, and anterior and posterior cingulate cortices. It is possible to relate these three sets of regions to three different sets of processes. Higher-order sensory cortices are involved in the perceptual representation of stimuli and their constituent features. The amygdala, striatum and orbitofrontal cortex mediate an association of this perceptual representation with emotional response, cognitive processing and behavioural motivation. Higher cortical regions are then involved in the construction of an internal model of the social environment, involving representation of other people, their social relationships with oneself, and the value of one’s actions in the context of a social group. To some extent, these three sets of processes build on one another, although their interactions are complex (FIG. 1). For organizational purposes, the sections that follow consider these neural structures roughly in the same order as above. Box 1 | Are our brains specialized for social cognition? Brains and social behaviours vary across different mammalian species. Primitive insectivores (for example, hedgehogs) already show tightly regulated maternal behaviours that allow extended development of their offspring; non-human primates (for example, chimpanzees) live in extended societies of a few dozen subjects; and modern humans have created societies that encompass millions of interacting people. There is no question that humans are exceedingly skilled at large-scale social interaction, but it remains a puzzle how best to account for such abilities. Under one hypothesis149, the competition for social skills led to the evolution of cognitive mechanisms for outsmarting others150, and fuelled the expansion of the human brain and perhaps the elaboration of certain neural systems151. In support of this idea, there is a correlation across primate species between the size of their social group and the relative volume of neocortex149. Hedgehog Chimpanzee Human Courtesy of Laura Roberts