正在加载图片...

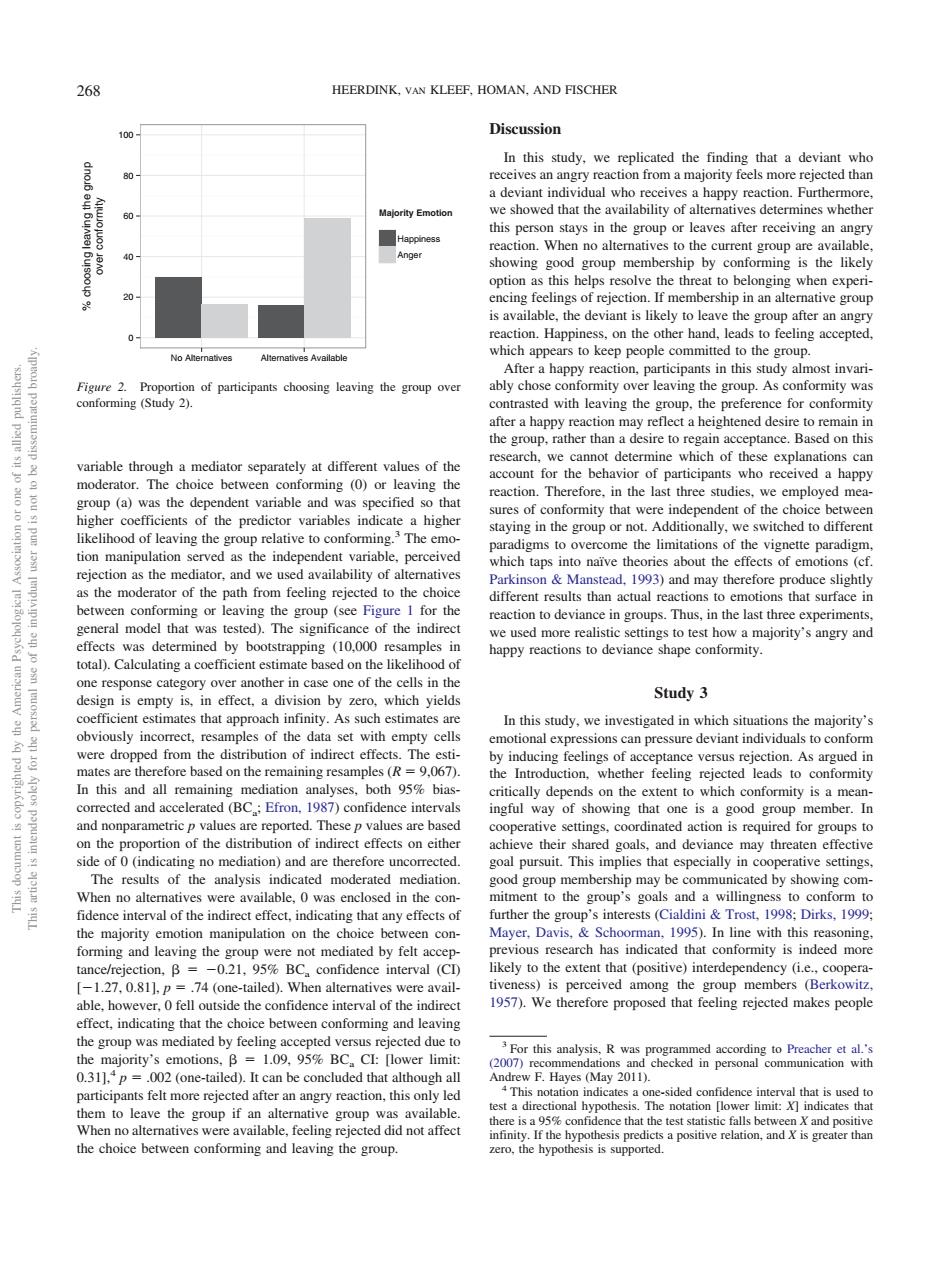

HEERDINK.VAN KLEEF.HOMAN.AND FISCHER Discussion this perso stays in the group or eiving an angr 20 Afte reaction,participants in this study almost invari er leaving th group.As c ty wa ed desre torem rather tha e to rega h of thes on I ariable through a mediator separately at different values of the ountfor the behavior of participan who receive I a happy The choice between conforming (0)or leaving the dent of the choice betweer of the in the group or no switched toc ren ving the group relative to conformin The em which taps into naive th about the effectsof s (ct 3)and may therefore gh山 of the path from fecling reje ed t see rg ion to devian in groups.Thus.in the last three experiment rmined by bootstrapping (10,000 in effect,a divi Study 3 inducin feein of tance versus As nd all ed and accele I(BC Efror 1987)confi of showing that one isa good group ngs ps nd cating no mediation)and are th goal pursuit.This implies that especially in cooperative setings val of the tha the group 1998:Dirks,1999 has indicated that conformity is indeed mor -021. 95 BC.confid interdepend 1957).We therefore proposed that feeling rejected makes people that th ce between confo For this an 4 02 (one-tailed).It gy201 angry rea sided con onal hy eeling tween cor ming and leaving the group variable through a mediator separately at different values of the moderator. The choice between conforming (0) or leaving the group (a) was the dependent variable and was specified so that higher coefficients of the predictor variables indicate a higher likelihood of leaving the group relative to conforming.3 The emotion manipulation served as the independent variable, perceived rejection as the mediator, and we used availability of alternatives as the moderator of the path from feeling rejected to the choice between conforming or leaving the group (see Figure 1 for the general model that was tested). The significance of the indirect effects was determined by bootstrapping (10,000 resamples in total). Calculating a coefficient estimate based on the likelihood of one response category over another in case one of the cells in the design is empty is, in effect, a division by zero, which yields coefficient estimates that approach infinity. As such estimates are obviously incorrect, resamples of the data set with empty cells were dropped from the distribution of indirect effects. The estimates are therefore based on the remaining resamples (R 9,067). In this and all remaining mediation analyses, both 95% biascorrected and accelerated (BCa; Efron, 1987) confidence intervals and nonparametric p values are reported. These p values are based on the proportion of the distribution of indirect effects on either side of 0 (indicating no mediation) and are therefore uncorrected. The results of the analysis indicated moderated mediation. When no alternatives were available, 0 was enclosed in the confidence interval of the indirect effect, indicating that any effects of the majority emotion manipulation on the choice between conforming and leaving the group were not mediated by felt acceptance/rejection, 0.21, 95% BCa confidence interval (CI) [1.27, 0.81], p .74 (one-tailed). When alternatives were available, however, 0 fell outside the confidence interval of the indirect effect, indicating that the choice between conforming and leaving the group was mediated by feeling accepted versus rejected due to the majority’s emotions, 1.09, 95% BCa CI: [lower limit: 0.31],4 p .002 (one-tailed). It can be concluded that although all participants felt more rejected after an angry reaction, this only led them to leave the group if an alternative group was available. When no alternatives were available, feeling rejected did not affect the choice between conforming and leaving the group. Discussion In this study, we replicated the finding that a deviant who receives an angry reaction from a majority feels more rejected than a deviant individual who receives a happy reaction. Furthermore, we showed that the availability of alternatives determines whether this person stays in the group or leaves after receiving an angry reaction. When no alternatives to the current group are available, showing good group membership by conforming is the likely option as this helps resolve the threat to belonging when experiencing feelings of rejection. If membership in an alternative group is available, the deviant is likely to leave the group after an angry reaction. Happiness, on the other hand, leads to feeling accepted, which appears to keep people committed to the group. After a happy reaction, participants in this study almost invariably chose conformity over leaving the group. As conformity was contrasted with leaving the group, the preference for conformity after a happy reaction may reflect a heightened desire to remain in the group, rather than a desire to regain acceptance. Based on this research, we cannot determine which of these explanations can account for the behavior of participants who received a happy reaction. Therefore, in the last three studies, we employed measures of conformity that were independent of the choice between staying in the group or not. Additionally, we switched to different paradigms to overcome the limitations of the vignette paradigm, which taps into naïve theories about the effects of emotions (cf. Parkinson & Manstead, 1993) and may therefore produce slightly different results than actual reactions to emotions that surface in reaction to deviance in groups. Thus, in the last three experiments, we used more realistic settings to test how a majority’s angry and happy reactions to deviance shape conformity. Study 3 In this study, we investigated in which situations the majority’s emotional expressions can pressure deviant individuals to conform by inducing feelings of acceptance versus rejection. As argued in the Introduction, whether feeling rejected leads to conformity critically depends on the extent to which conformity is a meaningful way of showing that one is a good group member. In cooperative settings, coordinated action is required for groups to achieve their shared goals, and deviance may threaten effective goal pursuit. This implies that especially in cooperative settings, good group membership may be communicated by showing commitment to the group’s goals and a willingness to conform to further the group’s interests (Cialdini & Trost, 1998; Dirks, 1999; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995). In line with this reasoning, previous research has indicated that conformity is indeed more likely to the extent that (positive) interdependency (i.e., cooperativeness) is perceived among the group members (Berkowitz, 1957). We therefore proposed that feeling rejected makes people 3 For this analysis, R was programmed according to Preacher et al.’s (2007) recommendations and checked in personal communication with Andrew F. Hayes (May 2011). 4 This notation indicates a one-sided confidence interval that is used to test a directional hypothesis. The notation [lower limit: X] indicates that there is a 95% confidence that the test statistic falls between X and positive infinity. If the hypothesis predicts a positive relation, and X is greater than zero, the hypothesis is supported. 0 20 40 60 80 100 No Alternatives Alternatives Available % choosing leaving the group over conformity Majority Emotion Happiness Anger Figure 2. Proportion of participants choosing leaving the group over conforming (Study 2). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 268 HEERDINK, VAN KLEEF, HOMAN, AND FISCHER��