正在加载图片...

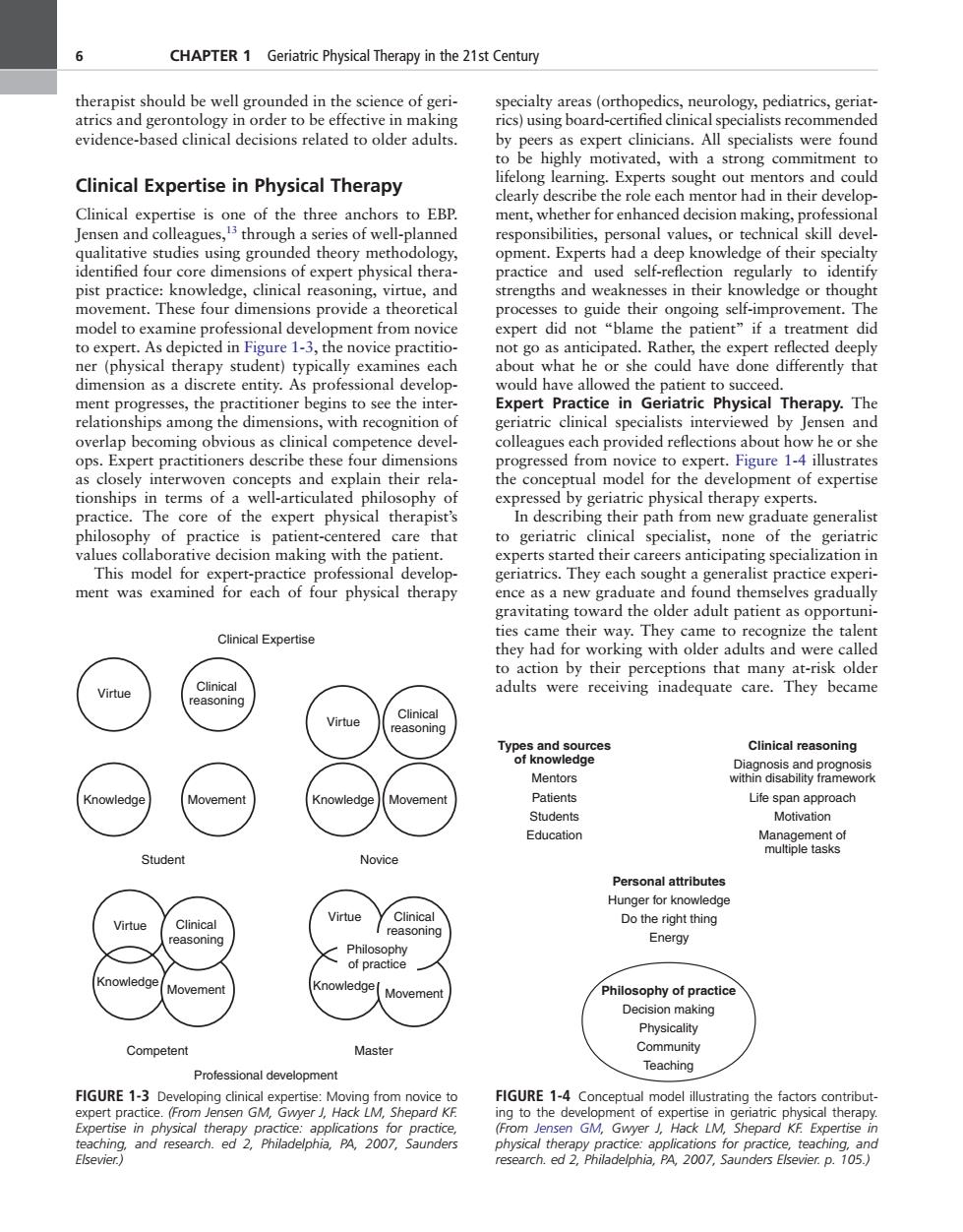

6 CHAPTER 1 Geriatric Physical Therapy in the 21st Century atricpist should be well grounded n ooidrakin s recommen ions related to were Clinical Expertise in Physical Therapy lifelong learning.Experts sought out mentors and could Clinical 15 of the three ancho EB er for enhanc sion m alt practice and used self-reflection regularly to identif movwdge chnical reasoning,vei strengths and weaknesses in their knowledge or though ou proce thei ongoing se nprovement :1-3.hment from ner(physical therapy student)typically examines each about what he or she could have done differently that dimension as a disc rete entity.As professional develop- ul have allowed the pa ment progresses,the egins to see th Exper actce The apy.The ps a an h ops.Expert practitioners describe these four dimensions ssed from novice to expert.Figure 1-4 illustrates as closely interwoven concepts and explain their rela tionships in terms o vell-articula ophy expre dcs generalis f a decision making with the patient. erts started their careers anticipating specialization in This model for expert-practice professional develop- ment was examined for each of four physical therapy ence as a nev ndradni Clinical Expertise they had for workine with older adults and were called to action by their perceptions that many at-risk older adults were receiving inadequate care.They became Virtue Life sp ach 04 Students Education Novice nal attribute Hunger for knowledo irtue Do the right thing Energy em Phi sophy of practic Competen Maste Teaching Professional development FIGURE 1-3 De FIGURE 1-4 Conceptual model rating the factors From GM G Hack LN rd KF.Expertise in6 CHAPTER 1 Geriatric Physical Therapy in the 21st Century therapist should be well grounded in the science of geriatrics and gerontology in order to be effective in making evidence-based clinical decisions related to older adults. Clinical Expertise in Physical Therapy Clinical expertise is one of the three anchors to EBP. Jensen and colleagues,13 through a series of well-planned qualitative studies using grounded theory methodology, identified four core dimensions of expert physical therapist practice: knowledge, clinical reasoning, virtue, and movement. These four dimensions provide a theoretical model to examine professional development from novice to expert. As depicted in Figure 1-3, the novice practitioner (physical therapy student) typically examines each dimension as a discrete entity. As professional development progresses, the practitioner begins to see the interrelationships among the dimensions, with recognition of overlap becoming obvious as clinical competence develops. Expert practitioners describe these four dimensions as closely interwoven concepts and explain their relationships in terms of a well-articulated philosophy of practice. The core of the expert physical therapist’s philosophy of practice is patient-centered care that values collaborative decision making with the patient. This model for expert-practice professional development was examined for each of four physical therapy specialty areas (orthopedics, neurology, pediatrics, geriatrics) using board-certified clinical specialists recommended by peers as expert clinicians. All specialists were found to be highly motivated, with a strong commitment to lifelong learning. Experts sought out mentors and could clearly describe the role each mentor had in their development, whether for enhanced decision making, professional responsibilities, personal values, or technical skill development. Experts had a deep knowledge of their specialty practice and used self-reflection regularly to identify strengths and weaknesses in their knowledge or thought processes to guide their ongoing self-improvement. The expert did not “blame the patient” if a treatment did not go as anticipated. Rather, the expert reflected deeply about what he or she could have done differently that would have allowed the patient to succeed. Expert Practice in Geriatric Physical Therapy. The geriatric clinical specialists interviewed by Jensen and colleagues each provided reflections about how he or she progressed from novice to expert. Figure 1-4 illustrates the conceptual model for the development of expertise expressed by geriatric physical therapy experts. In describing their path from new graduate generalist to geriatric clinical specialist, none of the geriatric experts started their careers anticipating specialization in geriatrics. They each sought a generalist practice experience as a new graduate and found themselves gradually gravitating toward the older adult patient as opportunities came their way. They came to recognize the talent they had for working with older adults and were called to action by their perceptions that many at-risk older adults were receiving inadequate care. They became Clinical Expertise Virtue Knowledge Clinical reasoning Movement Virtue Knowledge Clinical reasoning Movement Student Novice Virtue Knowledge Clinical reasoning Movement Competent Virtue Knowledge Clinical reasoning Movement Master Professional development Philosophy of practice FIGURE 1-3 Developing clinical expertise: Moving from novice to expert practice. (From Jensen GM, Gwyer J, Hack LM, Shepard KF. Expertise in physical therapy practice: applications for practice, teaching, and research. ed 2, Philadelphia, PA, 2007, Saunders Elsevier.) Types and sources of knowledge Mentors Patients Students Education Clinical reasoning Diagnosis and prognosis within disability framework Life span approach Motivation Management of multiple tasks Personal attributes Hunger for knowledge Do the right thing Energy Philosophy of practice Decision making Physicality Community Teaching FIGURE 1-4 Conceptual model illustrating the factors contributing to the development of expertise in geriatric physical therapy. (From Jensen GM, Gwyer J, Hack LM, Shepard KF. Expertise in physical therapy practice: applications for practice, teaching, and research. ed 2, Philadelphia, PA, 2007, Saunders Elsevier. p. 105.)