正在加载图片...

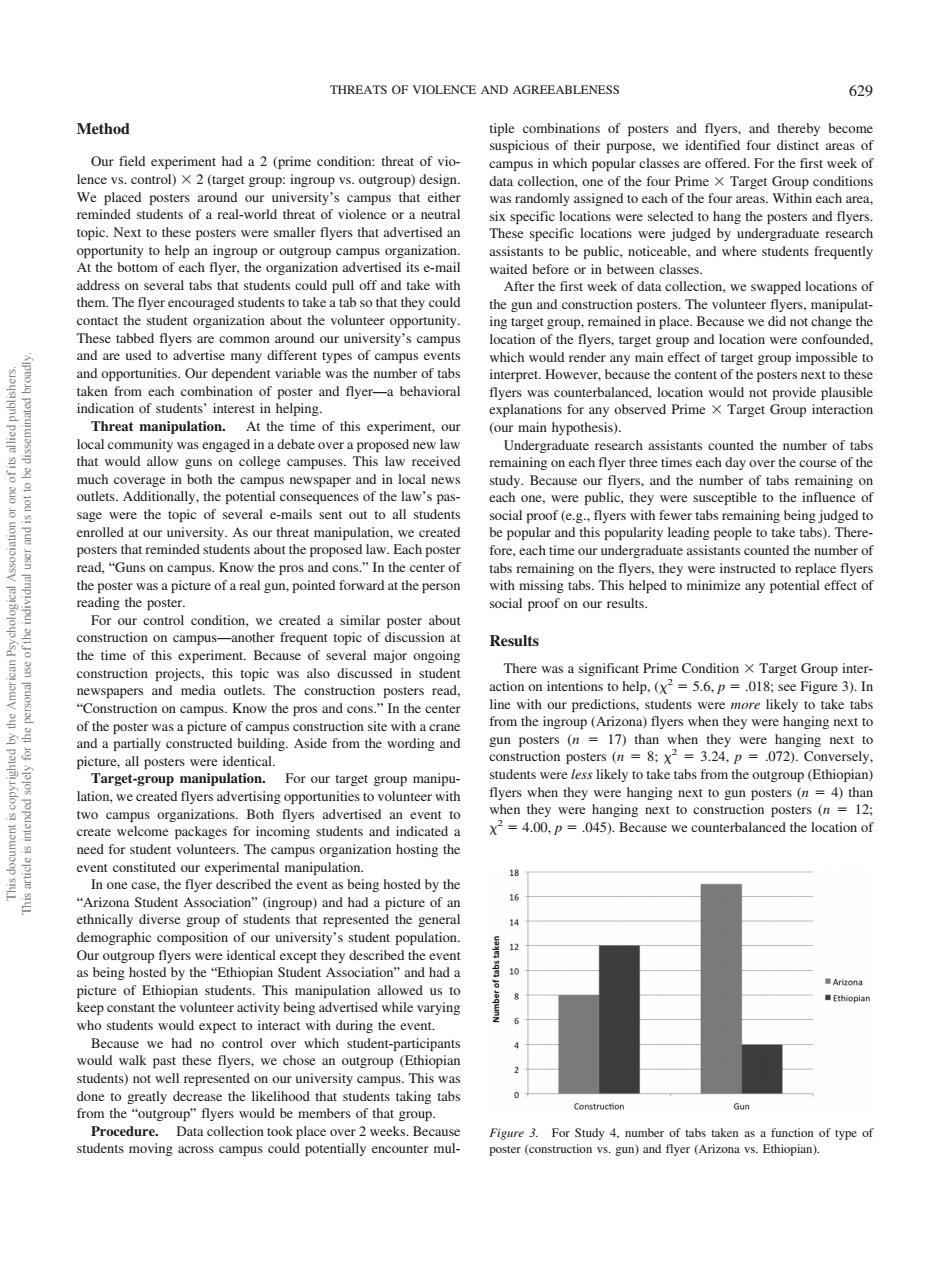

THREATS OF VIOLENCE AND AGREEABLENESS 629 Method Our field experiment had a2(prime condition:threat of vio mpus in which r cla re offered.For the first week o osters udents of a real-world threa hese speeifeoer ud by under carch cted to hang the posters and flve organi vertis hem.The flyer eabedyg nd are used to adv types of campus events which would render any main effect of targe ble u content o ication of studentsinterest in helping. ity was e ed in a dehate over a unted the number of tabs hat would al guns on collegec ampus day over the course of th onally,the potential nces of the law's pa one.were publie.they were susceptble to out to all stud th fe each time our ed the number o social proof on our results ction on campu itio Results time of this everal major on There was a significant Prime Condition X Target Group inte The construction read 01 Know the pros and con the d building.Aside from the wording and et-group target tudents were less likely to take tabs from the outgroup (Ethiopiar ed flyers ad were ns next to construction posters n 12 4.00.p =.045).Because we counterbalanced the location organization hosting the n one case,the flyer described the event as b ng hosted b y the ue)and had our un .1 icture of Ethiopian studen wed us to s)not well represented on our university cam This was Procedure. place over Figure3.For Study 4.number of tabs taken as a function of type of students moving across campus could potentially encounter mul- poster (construction vs.gun)and flyer (Arizona vs.Ethiopian). Method Our field experiment had a 2 (prime condition: threat of violence vs. control) 2 (target group: ingroup vs. outgroup) design. We placed posters around our university’s campus that either reminded students of a real-world threat of violence or a neutral topic. Next to these posters were smaller flyers that advertised an opportunity to help an ingroup or outgroup campus organization. At the bottom of each flyer, the organization advertised its e-mail address on several tabs that students could pull off and take with them. The flyer encouraged students to take a tab so that they could contact the student organization about the volunteer opportunity. These tabbed flyers are common around our university’s campus and are used to advertise many different types of campus events and opportunities. Our dependent variable was the number of tabs taken from each combination of poster and flyer—a behavioral indication of students’ interest in helping. Threat manipulation. At the time of this experiment, our local community was engaged in a debate over a proposed new law that would allow guns on college campuses. This law received much coverage in both the campus newspaper and in local news outlets. Additionally, the potential consequences of the law’s passage were the topic of several e-mails sent out to all students enrolled at our university. As our threat manipulation, we created posters that reminded students about the proposed law. Each poster read, “Guns on campus. Know the pros and cons.” In the center of the poster was a picture of a real gun, pointed forward at the person reading the poster. For our control condition, we created a similar poster about construction on campus—another frequent topic of discussion at the time of this experiment. Because of several major ongoing construction projects, this topic was also discussed in student newspapers and media outlets. The construction posters read, “Construction on campus. Know the pros and cons.” In the center of the poster was a picture of campus construction site with a crane and a partially constructed building. Aside from the wording and picture, all posters were identical. Target-group manipulation. For our target group manipulation, we created flyers advertising opportunities to volunteer with two campus organizations. Both flyers advertised an event to create welcome packages for incoming students and indicated a need for student volunteers. The campus organization hosting the event constituted our experimental manipulation. In one case, the flyer described the event as being hosted by the “Arizona Student Association” (ingroup) and had a picture of an ethnically diverse group of students that represented the general demographic composition of our university’s student population. Our outgroup flyers were identical except they described the event as being hosted by the “Ethiopian Student Association” and had a picture of Ethiopian students. This manipulation allowed us to keep constant the volunteer activity being advertised while varying who students would expect to interact with during the event. Because we had no control over which student-participants would walk past these flyers, we chose an outgroup (Ethiopian students) not well represented on our university campus. This was done to greatly decrease the likelihood that students taking tabs from the “outgroup” flyers would be members of that group. Procedure. Data collection took place over 2 weeks. Because students moving across campus could potentially encounter multiple combinations of posters and flyers, and thereby become suspicious of their purpose, we identified four distinct areas of campus in which popular classes are offered. For the first week of data collection, one of the four Prime Target Group conditions was randomly assigned to each of the four areas. Within each area, six specific locations were selected to hang the posters and flyers. These specific locations were judged by undergraduate research assistants to be public, noticeable, and where students frequently waited before or in between classes. After the first week of data collection, we swapped locations of the gun and construction posters. The volunteer flyers, manipulating target group, remained in place. Because we did not change the location of the flyers, target group and location were confounded, which would render any main effect of target group impossible to interpret. However, because the content of the posters next to these flyers was counterbalanced, location would not provide plausible explanations for any observed Prime Target Group interaction (our main hypothesis). Undergraduate research assistants counted the number of tabs remaining on each flyer three times each day over the course of the study. Because our flyers, and the number of tabs remaining on each one, were public, they were susceptible to the influence of social proof (e.g., flyers with fewer tabs remaining being judged to be popular and this popularity leading people to take tabs). Therefore, each time our undergraduate assistants counted the number of tabs remaining on the flyers, they were instructed to replace flyers with missing tabs. This helped to minimize any potential effect of social proof on our results. Results There was a significant Prime Condition Target Group interaction on intentions to help, (2 5.6, p .018; see Figure 3). In line with our predictions, students were more likely to take tabs from the ingroup (Arizona) flyers when they were hanging next to gun posters (n 17) than when they were hanging next to construction posters (n 8; 2 3.24, p .072). Conversely, students were less likely to take tabs from the outgroup (Ethiopian) flyers when they were hanging next to gun posters (n 4) than when they were hanging next to construction posters (n 12; 2 4.00, p .045). Because we counterbalanced the location of Figure 3. For Study 4, number of tabs taken as a function of type of poster (construction vs. gun) and flyer (Arizona vs. Ethiopian). THREATS OF VIOLENCE AND AGREEABLENESS 629 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly