正在加载图片...

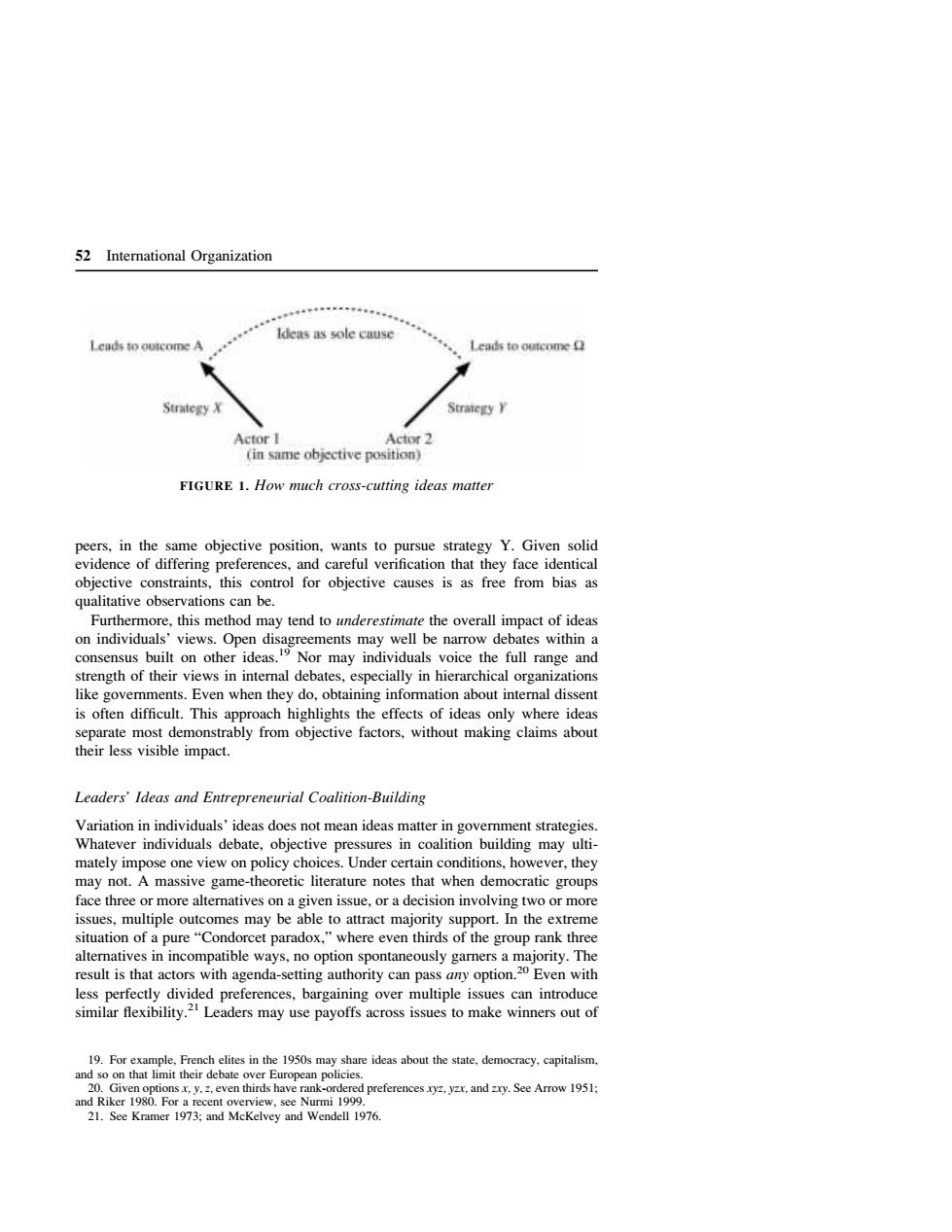

52 International Organization Ideas as sole cause Leads to outcome A Leads to outcome Strategy X Strategy Y Actor I Actor2 (in same objective position) FIGURE 1.How much cross-cutting ideas matter peers,in the same objective position,wants to pursue strategy Y.Given solid evidence of differing preferences,and careful verification that they face identical objective constraints,this control for objective causes is as free from bias as qualitative observations can be. Furthermore,this method may tend to underestimate the overall impact of ideas on individuals'views.Open disagreements may well be narrow debates within a consensus built on other ideas.19 Nor may individuals voice the full range and strength of their views in internal debates,especially in hierarchical organizations like goverments.Even when they do,obtaining information about internal dissent is often difficult.This approach highlights the effects of ideas only where ideas separate most demonstrably from objective factors,without making claims about their less visible impact. Leaders'Ideas and Entrepreneurial Coalition-Building Variation in individuals'ideas does not mean ideas matter in government strategies. Whatever individuals debate,objective pressures in coalition building may ulti- mately impose one view on policy choices.Under certain conditions,however,they may not.A massive game-theoretic literature notes that when democratic groups face three or more alternatives on a given issue,or a decision involving two or more issues,multiple outcomes may be able to attract majority support.In the extreme situation of a pure"Condorcet paradox,"where even thirds of the group rank three alternatives in incompatible ways,no option spontaneously garners a majority.The result is that actors with agenda-setting authority can pass any option.20 Even with less perfectly divided preferences,bargaining over multiple issues can introduce similar flexibility.21 Leaders may use payoffs across issues to make winners out of 19.For example,French elites in the 1950s may share ideas about the state,democracy,capitalism, and so on that limit their debate over European policies. 20.Given options x,y.z,even thirds have rank-ordered preferences .ryz,yzx,and zry.See Arrow 1951; and Riker 1980.For a recent overview,see Nurmi 1999. 21.See Kramer 1973:and McKelvey and Wendell 1976peers, in the same objective position, wants to pursue strategy Y. Given solid evidence of differing preferences, and careful verification that they face identical objective constraints, this control for objective causes is as free from bias as qualitative observations can be. Furthermore, this method may tend to underestimate the overall impact of ideas on individuals’ views. Open disagreements may well be narrow debates within a consensus built on other ideas.19 Nor may individuals voice the full range and strength of their views in internal debates, especially in hierarchical organizations like governments. Even when they do, obtaining information about internal dissent is often difficult. This approach highlights the effects of ideas only where ideas separate most demonstrably from objective factors, without making claims about their less visible impact. Leaders’ Ideas and Entrepreneurial Coalition-Building Variation in individuals’ ideas does not mean ideas matter in government strategies. Whatever individuals debate, objective pressures in coalition building may ultimately impose one view on policy choices. Under certain conditions, however, they may not. A massive game-theoretic literature notes that when democratic groups face three or more alternatives on a given issue, or a decision involving two or more issues, multiple outcomes may be able to attract majority support. In the extreme situation of a pure “Condorcet paradox,” where even thirds of the group rank three alternatives in incompatible ways, no option spontaneously garners a majority. The result is that actors with agenda-setting authority can pass any option.20 Even with less perfectly divided preferences, bargaining over multiple issues can introduce similar flexibility.21 Leaders may use payoffs across issues to make winners out of 19. For example, French elites in the 1950s may share ideas about the state, democracy, capitalism, and so on that limit their debate over European policies. 20. Given options x, y, z, even thirds have rank-ordered preferences xyz, yzx, and zxy. See Arrow 1951; and Riker 1980. For a recent overview, see Nurmi 1999. 21. See Kramer 1973; and McKelvey and Wendell 1976. FIGURE 1. How much cross-cutting ideas matter 52 International Organization