正在加载图片...

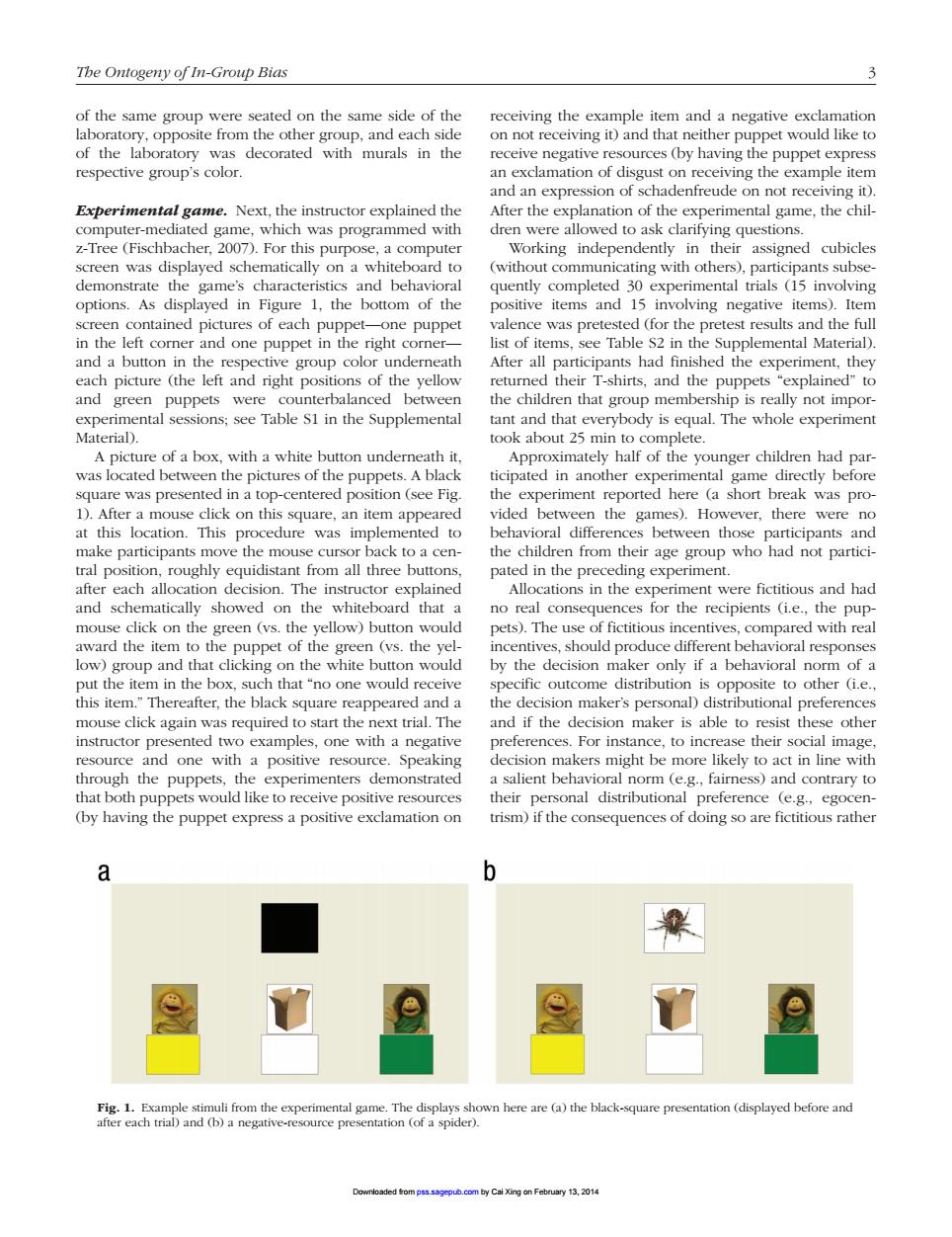

The Ontogeny of In-Group Bias of the same group were seated on the same side of the receiving the example item and a negative exclamation on not receiving it)and tha ororatory,opposhc the neither puppet would like to decorate ctive group's color ing the uppe nle iter and an expression of schadenfreude on not receiving it) Experimental game.Next,the instructor explained the After the explanation of the experimental game,the chil computer-me was programmed with dren were ano clantying question was dis aticall (ithout demonstrate the game's characteristics and behavioral quently completed 30 experimental trials (15 involving options.As displayed in Figure 1,the bottom of the positive items and 15 involving negative items).Iter one puppet was prete r the prete results and the fu and a butt After all had finisk enta ed the each picture (the left and right positions of the yellow retumed their T-shirts,and the pup and green puppets were counterbalanced between the children that group membership is really not impor. of a l half of the had was located between the pictures of the pu pets.A black ticipated in another experimental game directly befor square was presented in a top-centered position (see Fig the experiment reported here (a short break was pro 1).After a mouse lick on thi square,an item appearec the games).Ho ever,there were n was een the an tral position.roughly equidistant from all three button after each allocation decision.The instructor explained Allocations in the experiment were fictitious and had and schematically showed on whiteboard that no eal consequence for the recipients (i.e.,the pup mo mpared with rea low)group and that clicking on the white button would by the decision maker only if a behavioral norm of a put the item in the box,such that"no one would receive specific outcome distribution is opposite to other (i.e. this item."Thereafter,the black square reappearec and a sion makers personal)d clck again wa required to start the ext trial.Th Ir the on make able to resource and one with a positive resource speakin decision makers might be more likely to act in line with through the puppets,the experimenters demonstrated a salient behavioral norm (e.g.,fairness)and contrary to that both puppets would like to receive positive resources their personal distributional preference (e.g.,egocen (by having the puppet express a positive exclamation on trism)if the consequences of doing so are fictitious rathe b nuli fr n the ntal The displa are (a)the black displaved before and ce pre 1,2014 The Ontogeny of In-Group Bias 3 of the same group were seated on the same side of the laboratory, opposite from the other group, and each side of the laboratory was decorated with murals in the respective group’s color. Experimental game. Next, the instructor explained the computer-mediated game, which was programmed with z-Tree (Fischbacher, 2007). For this purpose, a computer screen was displayed schematically on a whiteboard to demonstrate the game’s characteristics and behavioral options. As displayed in Figure 1, the bottom of the screen contained pictures of each puppet—one puppet in the left corner and one puppet in the right corner— and a button in the respective group color underneath each picture (the left and right positions of the yellow and green puppets were counterbalanced between experimental sessions; see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). A picture of a box, with a white button underneath it, was located between the pictures of the puppets. A black square was presented in a top-centered position (see Fig. 1). After a mouse click on this square, an item appeared at this location. This procedure was implemented to make participants move the mouse cursor back to a central position, roughly equidistant from all three buttons, after each allocation decision. The instructor explained and schematically showed on the whiteboard that a mouse click on the green (vs. the yellow) button would award the item to the puppet of the green (vs. the yellow) group and that clicking on the white button would put the item in the box, such that “no one would receive this item.” Thereafter, the black square reappeared and a mouse click again was required to start the next trial. The instructor presented two examples, one with a negative resource and one with a positive resource. Speaking through the puppets, the experimenters demonstrated that both puppets would like to receive positive resources (by having the puppet express a positive exclamation on receiving the example item and a negative exclamation on not receiving it) and that neither puppet would like to receive negative resources (by having the puppet express an exclamation of disgust on receiving the example item and an expression of schadenfreude on not receiving it). After the explanation of the experimental game, the children were allowed to ask clarifying questions. Working independently in their assigned cubicles (without communicating with others), participants subsequently completed 30 experimental trials (15 involving positive items and 15 involving negative items). Item valence was pretested (for the pretest results and the full list of items, see Table S2 in the Supplemental Material). After all participants had finished the experiment, they returned their T-shirts, and the puppets “explained” to the children that group membership is really not important and that everybody is equal. The whole experiment took about 25 min to complete. Approximately half of the younger children had participated in another experimental game directly before the experiment reported here (a short break was provided between the games). However, there were no behavioral differences between those participants and the children from their age group who had not participated in the preceding experiment. Allocations in the experiment were fictitious and had no real consequences for the recipients (i.e., the puppets). The use of fictitious incentives, compared with real incentives, should produce different behavioral responses by the decision maker only if a behavioral norm of a specific outcome distribution is opposite to other (i.e., the decision maker’s personal) distributional preferences and if the decision maker is able to resist these other preferences. For instance, to increase their social image, decision makers might be more likely to act in line with a salient behavioral norm (e.g., fairness) and contrary to their personal distributional preference (e.g., egocentrism) if the consequences of doing so are fictitious rather Fig. 1. Example stimuli from the experimental game. The displays shown here are (a) the black-square presentation (displayed before and after each trial) and (b) a negative-resource presentation (of a spider). Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Cai Xing on February 13, 2014