正在加载图片...

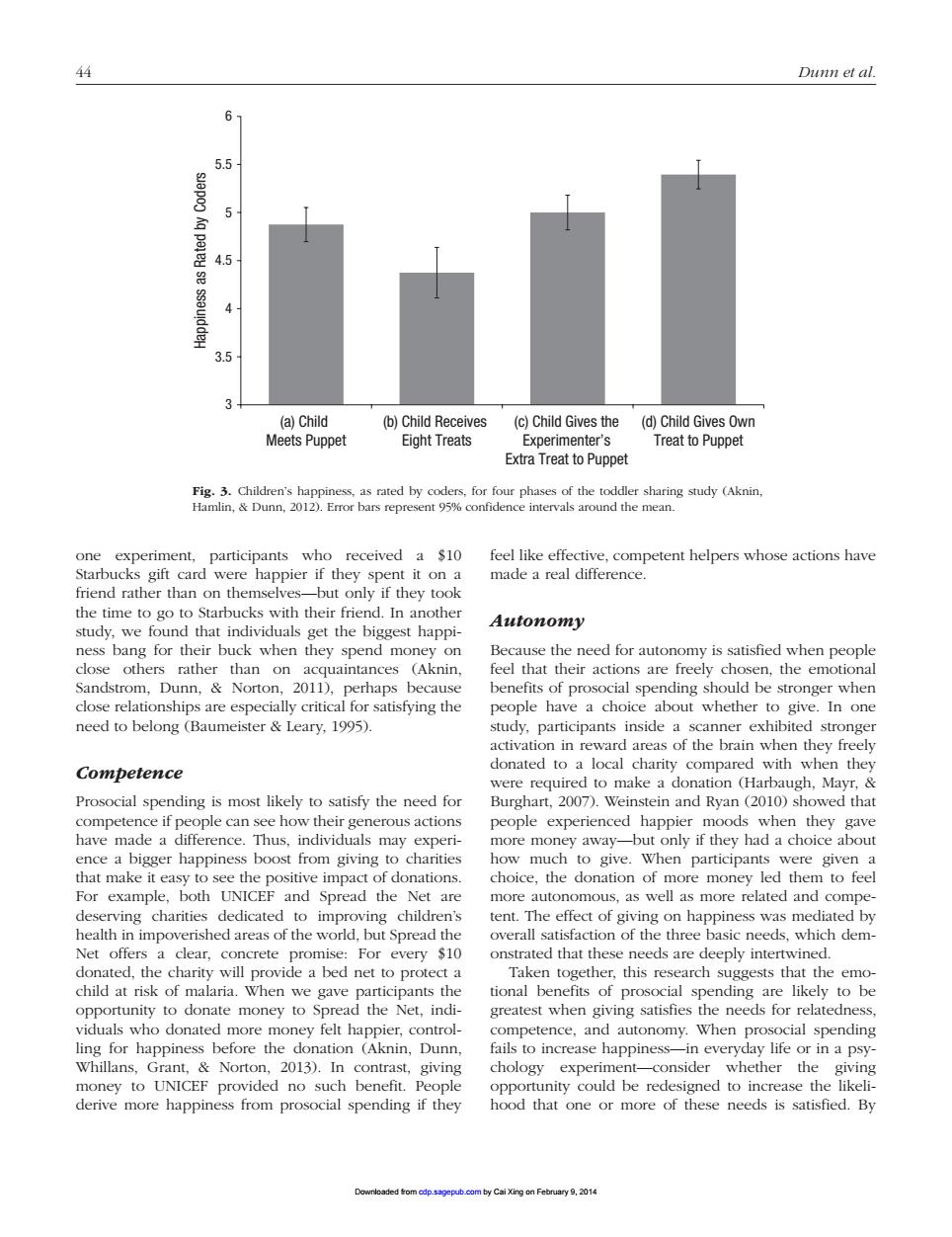

4 Dunn et al. 5,5 5 4 3.5 (a)Child (b)Child Receives (c)Child Gives the (d)Child Gives Own Meets Puppet Eight Treats Experimenter's Treat to puppet Extra Treat to Puppet one experiment,participants who received a $10 feel like effective,competent helpers whose actions have made a real difference. rather th an on thems they too study.we found that individuals get the biggest happi Autonomy ness bang for their buck when they spend mone on Because the need for autonomy is satisfied when people closeeu Norton.2011).perhaps because strom.Dunn, need (.1995). activation in reward areas of the brain when they freely Competence donated to a local charity compared with when they Prosocial spending is most likely the need for if see how thei enced har ds when they have made a difference.Thus.individuals may experi ence a bigger happiness boost from giving to charities oat make how much to give.When participants were given a easy to see the positive choice.the donaion of more money led them to fee The effect of o diated by overall satisfaction of the three basic needs,which dem Net offers a clear,concrete promise For every $10 d net to protect a arch suggests th e ad the Net st when ai ier control- competence.and autonomy.When p rosocial spending fails to increase happiness-in everyday life or in a psy 2013).1n giving chology expe uld be suc ending if they needs is satisficd.By44 Dunn et al. one experiment, participants who received a $10 Starbucks gift card were happier if they spent it on a friend rather than on themselves—but only if they took the time to go to Starbucks with their friend. In another study, we found that individuals get the biggest happiness bang for their buck when they spend money on close others rather than on acquaintances (Aknin, Sandstrom, Dunn, & Norton, 2011), perhaps because close relationships are especially critical for satisfying the need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Competence Prosocial spending is most likely to satisfy the need for competence if people can see how their generous actions have made a difference. Thus, individuals may experience a bigger happiness boost from giving to charities that make it easy to see the positive impact of donations. For example, both UNICEF and Spread the Net are deserving charities dedicated to improving children’s health in impoverished areas of the world, but Spread the Net offers a clear, concrete promise: For every $10 donated, the charity will provide a bed net to protect a child at risk of malaria. When we gave participants the opportunity to donate money to Spread the Net, individuals who donated more money felt happier, controlling for happiness before the donation (Aknin, Dunn, Whillans, Grant, & Norton, 2013). In contrast, giving money to UNICEF provided no such benefit. People derive more happiness from prosocial spending if they feel like effective, competent helpers whose actions have made a real difference. Autonomy Because the need for autonomy is satisfied when people feel that their actions are freely chosen, the emotional benefits of prosocial spending should be stronger when people have a choice about whether to give. In one study, participants inside a scanner exhibited stronger activation in reward areas of the brain when they freely donated to a local charity compared with when they were required to make a donation (Harbaugh, Mayr, & Burghart, 2007). Weinstein and Ryan (2010) showed that people experienced happier moods when they gave more money away—but only if they had a choice about how much to give. When participants were given a choice, the donation of more money led them to feel more autonomous, as well as more related and competent. The effect of giving on happiness was mediated by overall satisfaction of the three basic needs, which demonstrated that these needs are deeply intertwined. Taken together, this research suggests that the emotional benefits of prosocial spending are likely to be greatest when giving satisfies the needs for relatedness, competence, and autonomy. When prosocial spending fails to increase happiness—in everyday life or in a psychology experiment—consider whether the giving opportunity could be redesigned to increase the likelihood that one or more of these needs is satisfied. By 3 3.5 4 4.5 5 5.5 6 (a) Child Meets Puppet (b) Child Receives Eight Treats (c) Child Gives the Experimenter’s Extra Treat to Puppet (d) Child Gives Own Treat to Puppet Happiness as Rated by Coders Fig. 3. Children’s happiness, as rated by coders, for four phases of the toddler sharing study (Aknin, Hamlin, & Dunn, 2012). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals around the mean. Downloaded from cdp.sagepub.com by Cai Xing on February 9, 2014