正在加载图片...

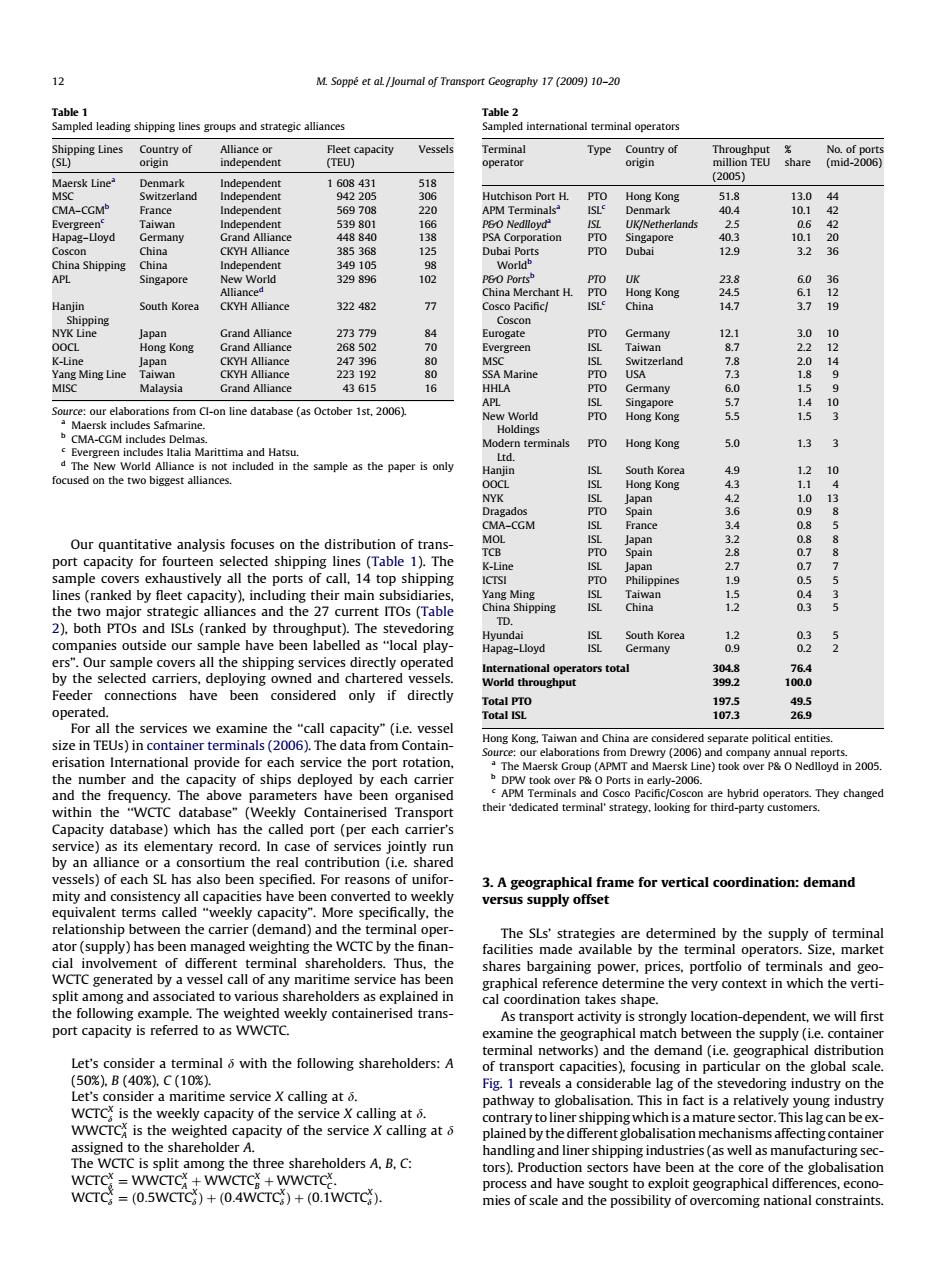

12 M.Soppe et aL/Joumal of Transport Geography 17 (2009)10-20 Table 1 Table 2 Sampled leading shipping lines groups and strategic alliances Sampled international terminal operators Shipping Lines Country of Alliance or Fleet capacity Vessels Terminal Type Country of Throughout No.of ports (SL) 01g1n independent (TEU) operator ongin million TEU share (mid-2006) Maersk Line Denmark Independent 1608431 518 (2005) MSC Switzerland Independent 942205 306 Hutchison Port H. PTO Hong Kong 51.8 13.0 44 CMA-CGMP France Independent 569708 220 APM Terminals" Denmark 40.4 10.1 Evergreen Taiwan Independent 539801 166 PSO Nedlloyd ISL UK/Netherlands 25 a.6 Hapag-Lloyd Germany Grand Alliance 448840 138 PSA Corporation PTO Singapore 40.3 10.1 Coscon China CKYH Alliance 385368 125 Dubai Ports PTO Dubai 12.9 3.2 36 China Shipping China Independent 349105 98 Worldb APL Singapore New World 329896 102 PSO Ports PTO UK 23.8 6.0 Alliances China merchant h PTo Hong Kong 245 6.1 12 Hanjin South Korea CKYH Alllance 322482 11 Cosco Pacific/ ISL China 14.7 3.7 Shipping Coscon NYK Line Japan Grand Alliance 273779 84 Eurogate PTO Germany 121 3.0 OOCL Hong Kong Grand Alliance 268502 70 Evergreen ISL Taiwan 8.7 22 12 K-Line Japan CKYH Alliance 247396 80 MSC ISL Switzerland 78 2.0 1 Yang Ming Line laiwan CKYH Alliance 223192 80 SSA Marine PTO USA 7.3 1.8 MISC Malaysia Grand Alliance 43615 16 HHLA PTO Germany 9 APL ISL 9 1.4 Source:our elaborations from Cl-on line database (as October 1st,2006). Singapore New World PTO Hong Kong 5.5 1.5 a Maersk includes Safmarine Holdings bCMA-CGM includes Delmas. Modern terminals PTO Hong Kong 5.0 1.3 Evergreen includes Italia Marittima and Hatsu Ltd. d The New World Alliance is not included in the sample as the paper is only Hanjin ISL South Korea 4.9 1.2 focused on the two biggest alliances. ISL Hong Kong 4.3 NYK ISL Japan 4.2 1.0 Dragados PTO Spain 0.9 8 CMA-CGM ISI France 3.4 0.8 Our quantitative analysis focuses on the distribution of trans- MOL ISL Japan 8 TCB PTO Spain port capacity for fourteen selected shipping lines(Table 1).The K-Line ISL lapan 2 87 7 sample covers exhaustively all the ports of call,14 top shipping ICTSI PTO Philippines . 0 5 lines(ranked by fleet capacity),including their main subsidiaries, Yang Ming ISI Taiwan 1.5 .4 the two major strategic alliances and the 27 current ITOs(Table China Shipping ISL China 1.2 0.3 5 2).both PTOs and ISLs(ranked by throughput).The stevedoring TD. Hyundai ISL South Korea 1.2 0.3 5 companies outside our sample have been labelled as"local play- Hapag-Lloyd ISL Germany 0.9 0.2 ers".Our sample covers all the shipping services directly operated International operators total 304.8 76.4 by the selected carriers,deploying owned and chartered vessels World throughput 3992 100.0 Feeder connections have been considered only if directly Total PTO 197.5 49.5 operated. Total ISL 107.3 26.9 For all the services we examine the "call capacity"(ie.vessel size in TEUs)in container terminals(2006).The data from Contain- Hong Kong.Taiwan and China are considered separate political entities. Source:our elaborations from Drewry (2006)and company annual reports. erisation International provide for each service the port rotation The Maersk Group(APMT and Maersk Line)took over P&O Nedlloyd in 2005. the number and the capacity of ships deployed by each carrier DPW took over P&O Ports in early-2006. and the frequency.The above parameters have been organised APM Terminals and Cosco Pacific/Coscon are hybrid operators.They changed within the "WCTC database"(Weekly Containerised Transport their'dedicated terminal'strategy,looking for third-party customers. Capacity database)which has the called port(per each carrier's service)as its elementary record.In case of services jointly run by an alliance or a consortium the real contribution (i.e.shared vessels)of each SL has also been specified.For reasons of unifor- 3.A geographical frame for vertical coordination:demand mity and consistency all capacities have been converted to weekly versus supply offset equivalent terms called "weekly capacity".More specifically,the relationship between the carrier(demand)and the terminal oper- The SLs'strategies are determined by the supply of terminal ator(supply)has been managed weighting the WCTC by the finan- facilities made available by the terminal operators.Size,market cial involvement of different terminal shareholders.Thus,the shares bargaining power,prices,portfolio of terminals and geo- WCTC generated by a vessel call of any maritime service has been graphical reference determine the very context in which the verti- split among and associated to various shareholders as explained in cal coordination takes shape. the following example.The weighted weekly containerised trans- As transport activity is strongly location-dependent,we will first port capacity is referred to as WWCTC. examine the geographical match between the supply (i.e.container terminal networks)and the demand(i.e.geographical distribution Let's consider a terminal 6 with the following shareholders:A of transport capacities),focusing in particular on the global scale. (50%).B(40%).C(10%). Fig.1 reveals a considerable lag of the stevedoring industry on the Let's consider a maritime service X calling at 5. pathway to globalisation.This in fact is a relatively young industry WCTC is the weekly capacity of the service X calling at 8. contrary to liner shipping which is a mature sector.This lag can be ex- WWCTC is the weighted capacity of the service X calling at 8 plained by the different globalisation mechanisms affecting container assigned to the shareholder A. handling and liner shipping industries(as well as manufacturing sec- The WCTC is split among the three shareholders A,B,C: tors).Production sectors have been at the core of the globalisation WCTC=WWCTC+WWCTC+WWCTC. process and have sought to exploit geographical differences,econo- WCTC =(0.5WCTC)+(0.4WCTC)+(0.1WCTC). mies of scale and the possibility of overcoming national constraintsOur quantitative analysis focuses on the distribution of transport capacity for fourteen selected shipping lines (Table 1). The sample covers exhaustively all the ports of call, 14 top shipping lines (ranked by fleet capacity), including their main subsidiaries, the two major strategic alliances and the 27 current ITOs (Table 2), both PTOs and ISLs (ranked by throughput). The stevedoring companies outside our sample have been labelled as ‘‘local players”. Our sample covers all the shipping services directly operated by the selected carriers, deploying owned and chartered vessels. Feeder connections have been considered only if directly operated. For all the services we examine the ‘‘call capacity” (i.e. vessel size in TEUs) in container terminals (2006). The data from Containerisation International provide for each service the port rotation, the number and the capacity of ships deployed by each carrier and the frequency. The above parameters have been organised within the ‘‘WCTC database” (Weekly Containerised Transport Capacity database) which has the called port (per each carrier’s service) as its elementary record. In case of services jointly run by an alliance or a consortium the real contribution (i.e. shared vessels) of each SL has also been specified. For reasons of uniformity and consistency all capacities have been converted to weekly equivalent terms called ‘‘weekly capacity”. More specifically, the relationship between the carrier (demand) and the terminal operator (supply) has been managed weighting the WCTC by the financial involvement of different terminal shareholders. Thus, the WCTC generated by a vessel call of any maritime service has been split among and associated to various shareholders as explained in the following example. The weighted weekly containerised transport capacity is referred to as WWCTC. Let’s consider a terminal d with the following shareholders: A (50%), B (40%), C (10%). Let’s consider a maritime service X calling at d. WCTCX d is the weekly capacity of the service X calling at d. WWCTCX A is the weighted capacity of the service X calling at d assigned to the shareholder A. The WCTC is split among the three shareholders A, B, C: WCTCX d ¼ WWCTCX A þ WWCTCX B þ WWCTCX C . WCTCX d ¼ ð0:5WCTCX d Þþð0:4WCTCX d Þþð0:1WCTCX d Þ. 3. A geographical frame for vertical coordination: demand versus supply offset The SLs’ strategies are determined by the supply of terminal facilities made available by the terminal operators. Size, market shares bargaining power, prices, portfolio of terminals and geographical reference determine the very context in which the vertical coordination takes shape. As transport activity is strongly location-dependent, we will first examine the geographical match between the supply (i.e. container terminal networks) and the demand (i.e. geographical distribution of transport capacities), focusing in particular on the global scale. Fig. 1 reveals a considerable lag of the stevedoring industry on the pathway to globalisation. This in fact is a relatively young industry contrary to liner shipping which is a mature sector. This lag can be explained by the different globalisationmechanisms affecting container handling and liner shipping industries (as well as manufacturing sectors). Production sectors have been at the core of the globalisation process and have sought to exploit geographical differences, economies of scale and the possibility of overcoming national constraints. Table 1 Sampled leading shipping lines groups and strategic alliances Shipping Lines (SL) Country of origin Alliance or independent Fleet capacity (TEU) Vessels Maersk Linea Denmark Independent 1 608 431 518 MSC Switzerland Independent 942 205 306 CMA–CGMb France Independent 569 708 220 Evergreenc Taiwan Independent 539 801 166 Hapag–Lloyd Germany Grand Alliance 448 840 138 Coscon China CKYH Alliance 385 368 125 China Shipping China Independent 349 105 98 APL Singapore New World Allianced 329 896 102 Hanjin Shipping South Korea CKYH Alliance 322 482 77 NYK Line Japan Grand Alliance 273 779 84 OOCL Hong Kong Grand Alliance 268 502 70 K-Line Japan CKYH Alliance 247 396 80 Yang Ming Line Taiwan CKYH Alliance 223 192 80 MISC Malaysia Grand Alliance 43 615 16 Source: our elaborations from CI-on line database (as October 1st, 2006). a Maersk includes Safmarine. b CMA-CGM includes Delmas. c Evergreen includes Italia Marittima and Hatsu. d The New World Alliance is not included in the sample as the paper is only focused on the two biggest alliances. Table 2 Sampled international terminal operators Terminal operator Type Country of origin Throughput million TEU (2005) % share No. of ports (mid-2006) Hutchison Port H. PTO Hong Kong 51.8 13.0 44 APM Terminalsa ISLc Denmark 40.4 10.1 42 P&O Nedlloyda ISL UK/Netherlands 2.5 0.6 42 PSA Corporation PTO Singapore 40.3 10.1 20 Dubai Ports Worldb PTO Dubai 12.9 3.2 36 P&O Portsb PTO UK 23.8 6.0 36 China Merchant H. PTO Hong Kong 24.5 6.1 12 Cosco Pacific/ Coscon ISLc China 14.7 3.7 19 Eurogate PTO Germany 12.1 3.0 10 Evergreen ISL Taiwan 8.7 2.2 12 MSC ISL Switzerland 7.8 2.0 14 SSA Marine PTO USA 7.3 1.8 9 HHLA PTO Germany 6.0 1.5 9 APL ISL Singapore 5.7 1.4 10 New World Holdings PTO Hong Kong 5.5 1.5 3 Modern terminals Ltd. PTO Hong Kong 5.0 1.3 3 Hanjin ISL South Korea 4.9 1.2 10 OOCL ISL Hong Kong 4.3 1.1 4 NYK ISL Japan 4.2 1.0 13 Dragados PTO Spain 3.6 0.9 8 CMA–CGM ISL France 3.4 0.8 5 MOL ISL Japan 3.2 0.8 8 TCB PTO Spain 2.8 0.7 8 K-Line ISL Japan 2.7 0.7 7 ICTSI PTO Philippines 1.9 0.5 5 Yang Ming ISL Taiwan 1.5 0.4 3 China Shipping TD. ISL China 1.2 0.3 5 Hyundai ISL South Korea 1.2 0.3 5 Hapag–Lloyd ISL Germany 0.9 0.2 2 International operators total 304.8 76.4 World throughput 399.2 100.0 Total PTO 197.5 49.5 Total ISL 107.3 26.9 Hong Kong, Taiwan and China are considered separate political entities. Source: our elaborations from Drewry (2006) and company annual reports. a The Maersk Group (APMT and Maersk Line) took over P& O Nedlloyd in 2005. b DPW took over P& O Ports in early-2006. c APM Terminals and Cosco Pacific/Coscon are hybrid operators. They changed their ‘dedicated terminal’ strategy, looking for third-party customers. 12 M. Soppé et al. / Journal of Transport Geography 17 (2009) 10–20