正在加载图片...

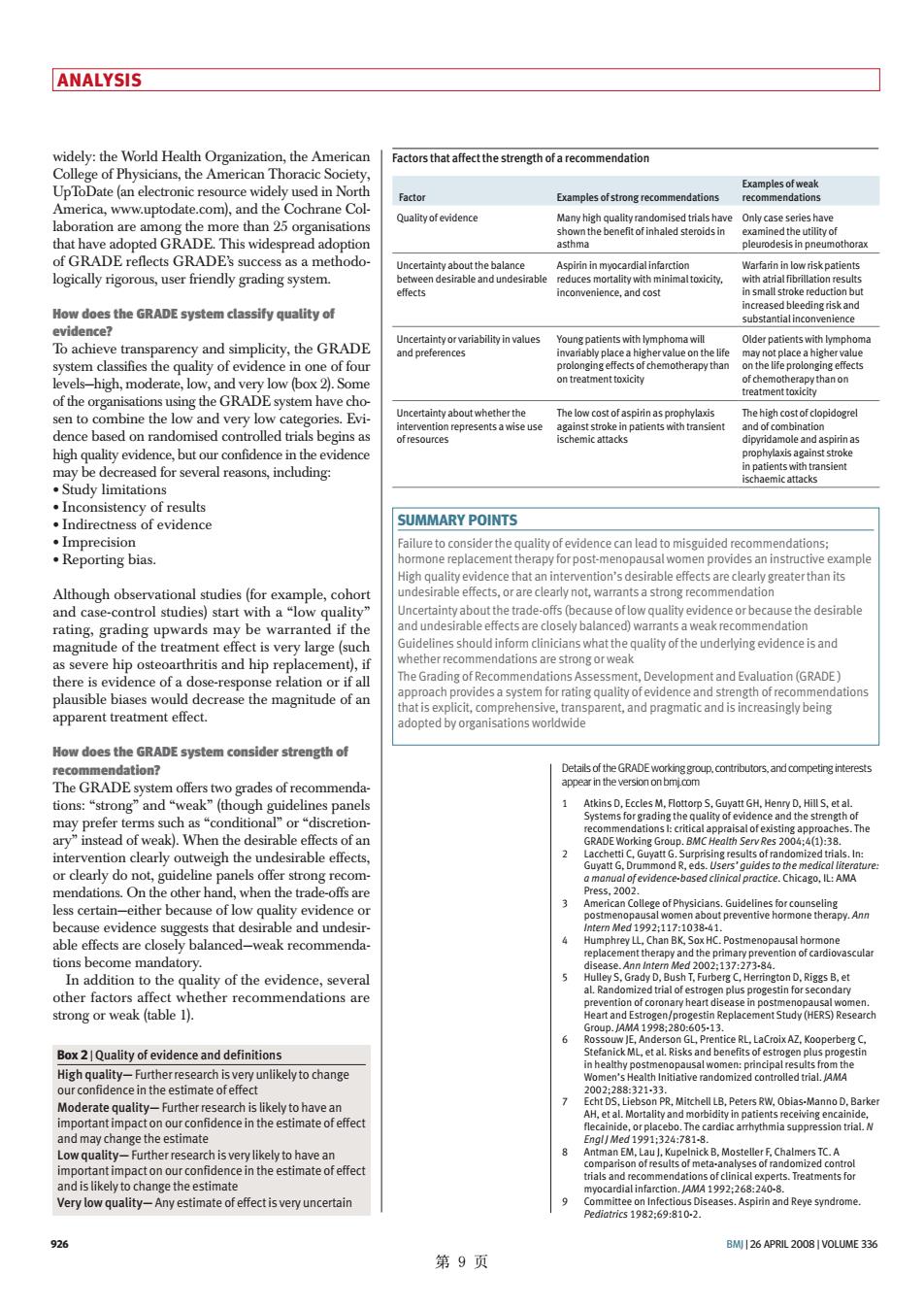

ANALYSIS widely:the World Health Organization,the American Factors that affect the strength of a recommendation les of strong recom ab How does the GRADE system classify quality of c and s ce a hi n one of fou of the c stem h SUMMARY POINTS Although obse studies(f and case-conolud) ne5holdatociniciaswhathegualyoftheundetyingevidenceisand ement ted angn5,eparent,andpagmatcandi5hceasingybeting "condi When he 1 able effec are weak recommenda 002:1 uality of the evidence,severa on D.Riggs B,et ether recommendations are nof coro 513 BoxQality of evidenceand definti h Initiative randomized ts iate uncertain 926 BM26 APRIL2008/VOLUME 336 第9页 926 BMJ | 26 APRIL 2008 | VOLUME 336 ANALYSIS Details of the GRADE working group, contributors, and competing interests appear in the version on bmj.com 1 Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Henry D, Hill S, et al. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches. The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res 2004;4(1):38. 2 Lacchetti C, Guyatt G. Surprising results of randomized trials. In: Guyatt G, Drummond R, eds. Users’ guides to the medical literature: a manual of evidence-based clinical practice. Chicago, IL: AMA Press, 2002. 3 American College of Physicians. Guidelines for counseling postmenopausal women about preventive hormone therapy. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:1038-41. 4 Humphrey LL, Chan BK, Sox HC. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:273-84. 5 Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg C, Herrington D, Riggs B, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA 1998;280:605-13. 6 Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33. 7 Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB, Peters RW, Obias-Manno D, Barker AH, et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo. The cardiac arrhythmia suppression trial. N Engl J Med 1991;324:781-8. 8 Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized control trials and recommendations of clinical experts. Treatments for myocardial infarction. JAMA 1992;268:240-8. 9 Committee on Infectious Diseases. Aspirin and Reye syndrome. Pediatrics 1982;69:810-2. widely: the World Health Organization, the American College of Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, UpToDate (an electronic resource widely used in North America, www.uptodate.com), and the Cochrane Collaboration are among the more than 25 organisations that have adopted GRADE. This widespread adoption of GRADE reflects GRADE’s success as a methodologically rigorous, user friendly grading system. How does the GRADE system classify quality of evidence? To achieve transparency and simplicity, the GRADE system classifies the quality of evidence in one of four levels—high, moderate, low, and very low (box 2). Some of the organisations using the GRADE system have chosen to combine the low and very low categories. Evidence based on randomised controlled trials begins as high quality evidence, but our confidence in the evidence may be decreased for several reasons, including: tStudy limitations tInconsistency of results tIndirectness of evidence tImprecision tReporting bias. Although observational studies (for example, cohort and case-control studies) start with a “low quality” rating, grading upwards may be warranted if the magnitude of the treatment effect is very large (such as severe hip osteoarthritis and hip replacement), if there is evidence of a dose-response relation or if all plausible biases would decrease the magnitude of an apparent treatment effect. How does the GRADE system consider strength of recommendation? The GRADE system offers two grades of recommendations: “strong” and “weak” (though guidelines panels may prefer terms such as “conditional” or “discretionary” instead of weak). When the desirable effects of an intervention clearly outweigh the undesirable effects, or clearly do not, guideline panels offer strong recommendations. On the other hand, when the trade-offs are less certain—either because of low quality evidence or because evidence suggests that desirable and undesirable effects are closely balanced—weak recommendations become mandatory. In addition to the quality of the evidence, several other factors affect whether recommendations are strong or weak (table 1). SUMMARY POINTS Failure to consider the quality of evidence can lead to misguided recommendations; hormone replacement therapy for post-menopausal women provides an instructive example High quality evidence that an intervention’s desirable effects are clearly greater than its undesirable effects, or are clearly not, warrants a strong recommendation Uncertainty about the trade-offs (because of low quality evidence or because the desirable and undesirable effects are closely balanced) warrants a weak recommendation Guidelines should inform clinicians what the quality of the underlying evidence is and whether recommendations are strong or weak The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE ) approach provides a system for rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations that is explicit, comprehensive, transparent, and pragmatic and is increasingly being adopted by organisations worldwide Box 2 | Quality of evidence and definitions High quality— Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality— Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality— Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality— Any estimate of effect is very uncertain Factors that affect the strength of a recommendation Factor Examples of strong recommendations Examples of weak recommendations Quality of evidence Many high quality randomised trials have shown the benefit of inhaled steroids in asthma Only case series have examined the utility of pleurodesis in pneumothorax Uncertainty about the balance between desirable and undesirable effects Aspirin in myocardial infarction reduces mortality with minimal toxicity, inconvenience, and cost Warfarin in low risk patients with atrial fibrillation results in small stroke reduction but increased bleeding risk and substantial inconvenience Uncertainty or variability in values and preferences Young patients with lymphoma will invariably place a higher value on the life prolonging effects of chemotherapy than on treatment toxicity Older patients with lymphoma may not place a higher value on the life prolonging effects of chemotherapy than on treatment toxicity Uncertainty about whether the intervention represents a wise use of resources The low cost of aspirin as prophylaxis against stroke in patients with transient ischemic attacks The high cost of clopidogrel and of combination dipyridamole and aspirin as prophylaxis against stroke in patients with transient ischaemic attacks 第 9 页