正在加载图片...

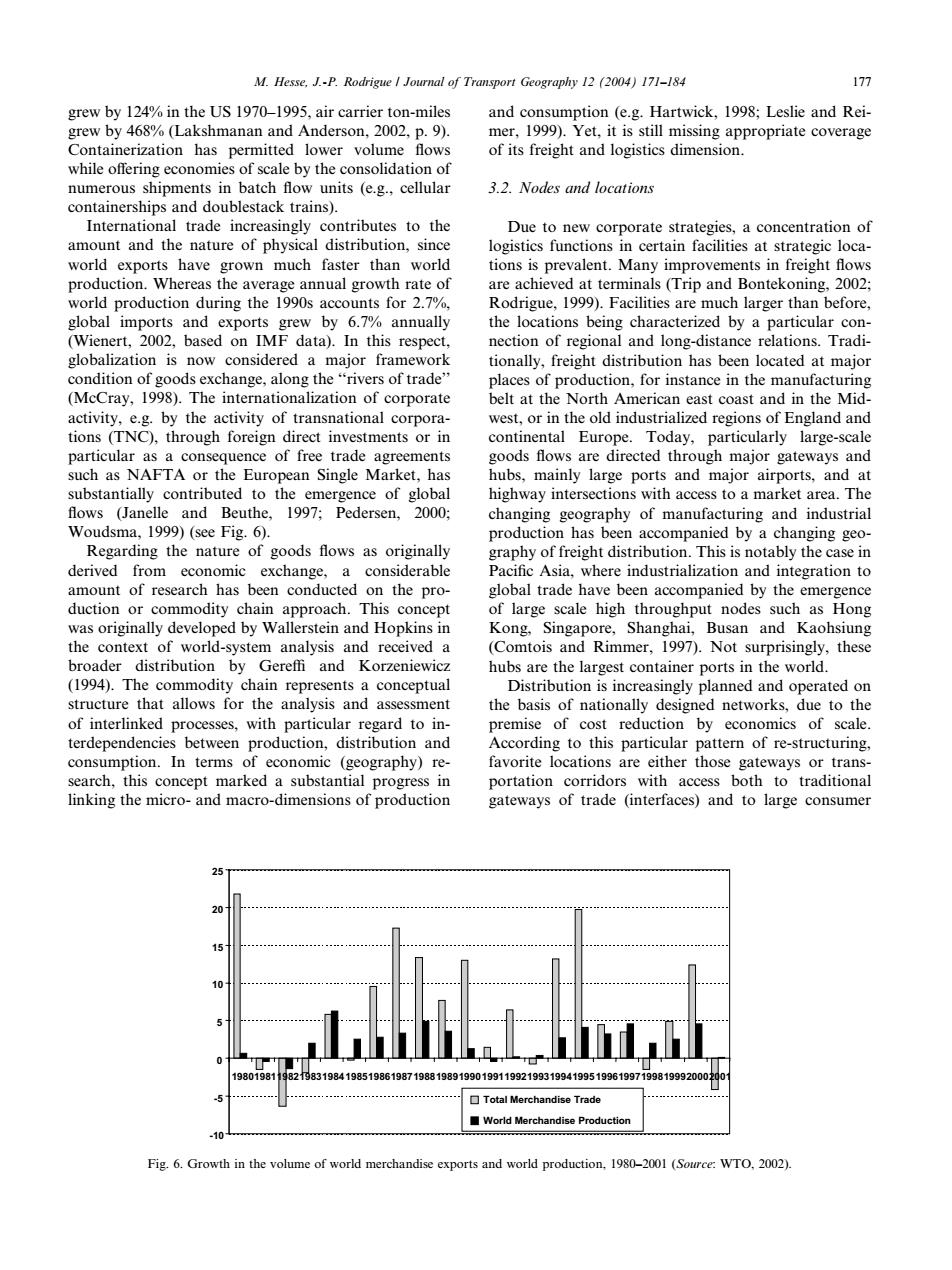

M.Hesse,J.-P.Rodrigue I Journal of Transport Geography 12(2004)171-184 177 grew by 124%in the US 1970-1995,air carrier ton-miles and consumption (e.g.Hartwick,1998;Leslie and Rei- grew by 468%(Lakshmanan and Anderson,2002,p.9). mer,1999).Yet,it is still missing appropriate coverage Containerization has permitted lower volume flows of its freight and logistics dimension. while offering economies of scale by the consolidation of numerous shipments in batch flow units (e.g.,cellular 3.2.Nodes and locations containerships and doublestack trains). International trade increasingly contributes to the Due to new corporate strategies,a concentration of amount and the nature of physical distribution,since logistics functions in certain facilities at strategic loca- world exports have grown much faster than world tions is prevalent.Many improvements in freight flows production.Whereas the average annual growth rate of are achieved at terminals(Trip and Bontekoning,2002; world production during the 1990s accounts for 2.7%, Rodrigue,1999).Facilities are much larger than before, global imports and exports grew by 6.7%annually the locations being characterized by a particular con- (Wienert,2002,based on IMF data).In this respect, nection of regional and long-distance relations.Tradi- globalization is now considered a major framework tionally,freight distribution has been located at major condition of goods exchange,along the "rivers of trade" places of production,for instance in the manufacturing (McCray,1998).The internationalization of corporate belt at the North American east coast and in the Mid- activity,e.g.by the activity of transnational corpora- west,or in the old industrialized regions of England and tions (TNC).through foreign direct investments or in continental Europe.Today,particularly large-scale particular as a consequence of free trade agreements goods flows are directed through major gateways and such as NAFTA or the European Single Market,has hubs,mainly large ports and major airports,and at substantially contributed to the emergence of global highway intersections with access to a market area.The flows (Janelle and Beuthe,1997;Pedersen,2000; changing geography of manufacturing and industrial Woudsma,1999)(see Fig.6). production has been accompanied by a changing geo- Regarding the nature of goods flows as originally graphy of freight distribution.This is notably the case in derived from economic exchange,a considerable Pacific Asia,where industrialization and integration to amount of research has been conducted on the pro- global trade have been accompanied by the emergence duction or commodity chain approach.This concept of large scale high throughput nodes such as Hong was originally developed by Wallerstein and Hopkins in Kong,Singapore,Shanghai,Busan and Kaohsiung the context of world-system analysis and received a (Comtois and Rimmer,1997).Not surprisingly,these broader distribution by Gereffi and Korzeniewicz hubs are the largest container ports in the world. (1994).The commodity chain represents a conceptual Distribution is increasingly planned and operated on structure that allows for the analysis and assessment the basis of nationally designed networks,due to the of interlinked processes,with particular regard to in- premise of cost reduction by economics of scale. terdependencies between production,distribution and According to this particular pattern of re-structuring, consumption.In terms of economic (geography)re- favorite locations are either those gateways or trans- search,this concept marked a substantial progress in portation corridors with access both to traditional linking the micro-and macro-dimensions of production gateways of trade (interfaces)and to large consumer 9801981 8319841985198619871988198919901991199219931994199519961997199819992000 Total Merchandise Trade World Merchandise Production 10 Fig.6.Growth in the volume of world merchandise exports and world production,1980-2001 (Source:WTO,2002).grew by 124% in the US 1970–1995, air carrier ton-miles grew by 468% (Lakshmanan and Anderson, 2002, p. 9). Containerization has permitted lower volume flows while offering economies of scale by the consolidation of numerous shipments in batch flow units (e.g., cellular containerships and doublestack trains). International trade increasingly contributes to the amount and the nature of physical distribution, since world exports have grown much faster than world production. Whereas the average annual growth rate of world production during the 1990s accounts for 2.7%, global imports and exports grew by 6.7% annually (Wienert, 2002, based on IMF data). In this respect, globalization is now considered a major framework condition of goods exchange, along the ‘‘rivers of trade’’ (McCray, 1998). The internationalization of corporate activity, e.g. by the activity of transnational corporations (TNC), through foreign direct investments or in particular as a consequence of free trade agreements such as NAFTA or the European Single Market, has substantially contributed to the emergence of global flows (Janelle and Beuthe, 1997; Pedersen, 2000; Woudsma, 1999) (see Fig. 6). Regarding the nature of goods flows as originally derived from economic exchange, a considerable amount of research has been conducted on the production or commodity chain approach. This concept was originally developed by Wallerstein and Hopkins in the context of world-system analysis and received a broader distribution by Gereffi and Korzeniewicz (1994). The commodity chain represents a conceptual structure that allows for the analysis and assessment of interlinked processes, with particular regard to interdependencies between production, distribution and consumption. In terms of economic (geography) research, this concept marked a substantial progress in linking the micro- and macro-dimensions of production and consumption (e.g. Hartwick, 1998; Leslie and Reimer, 1999). Yet, it is still missing appropriate coverage of its freight and logistics dimension. 3.2. Nodes and locations Due to new corporate strategies, a concentration of logistics functions in certain facilities at strategic locations is prevalent. Many improvements in freight flows are achieved at terminals (Trip and Bontekoning, 2002; Rodrigue, 1999). Facilities are much larger than before, the locations being characterized by a particular connection of regional and long-distance relations. Traditionally, freight distribution has been located at major places of production, for instance in the manufacturing belt at the North American east coast and in the Midwest, or in the old industrialized regions of England and continental Europe. Today, particularly large-scale goods flows are directed through major gateways and hubs, mainly large ports and major airports, and at highway intersections with access to a market area. The changing geography of manufacturing and industrial production has been accompanied by a changing geography of freight distribution. This is notably the case in Pacific Asia, where industrialization and integration to global trade have been accompanied by the emergence of large scale high throughput nodes such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, Busan and Kaohsiung (Comtois and Rimmer, 1997). Not surprisingly, these hubs are the largest container ports in the world. Distribution is increasingly planned and operated on the basis of nationally designed networks, due to the premise of cost reduction by economics of scale. According to this particular pattern of re-structuring, favorite locations are either those gateways or transportation corridors with access both to traditional gateways of trade (interfaces) and to large consumer -10 -5 0 5 10 15 20 25 1980198119821983198419851986198719881989199019911992199319941995199619971998199920002001 Total Merchandise Trade World Merchandise Production Fig. 6. Growth in the volume of world merchandise exports and world production, 1980–2001 (Source: WTO, 2002). M. Hesse, J.-P. Rodrigue / Journal of Transport Geography 12 (2004) 171–184 177