正在加载图片...

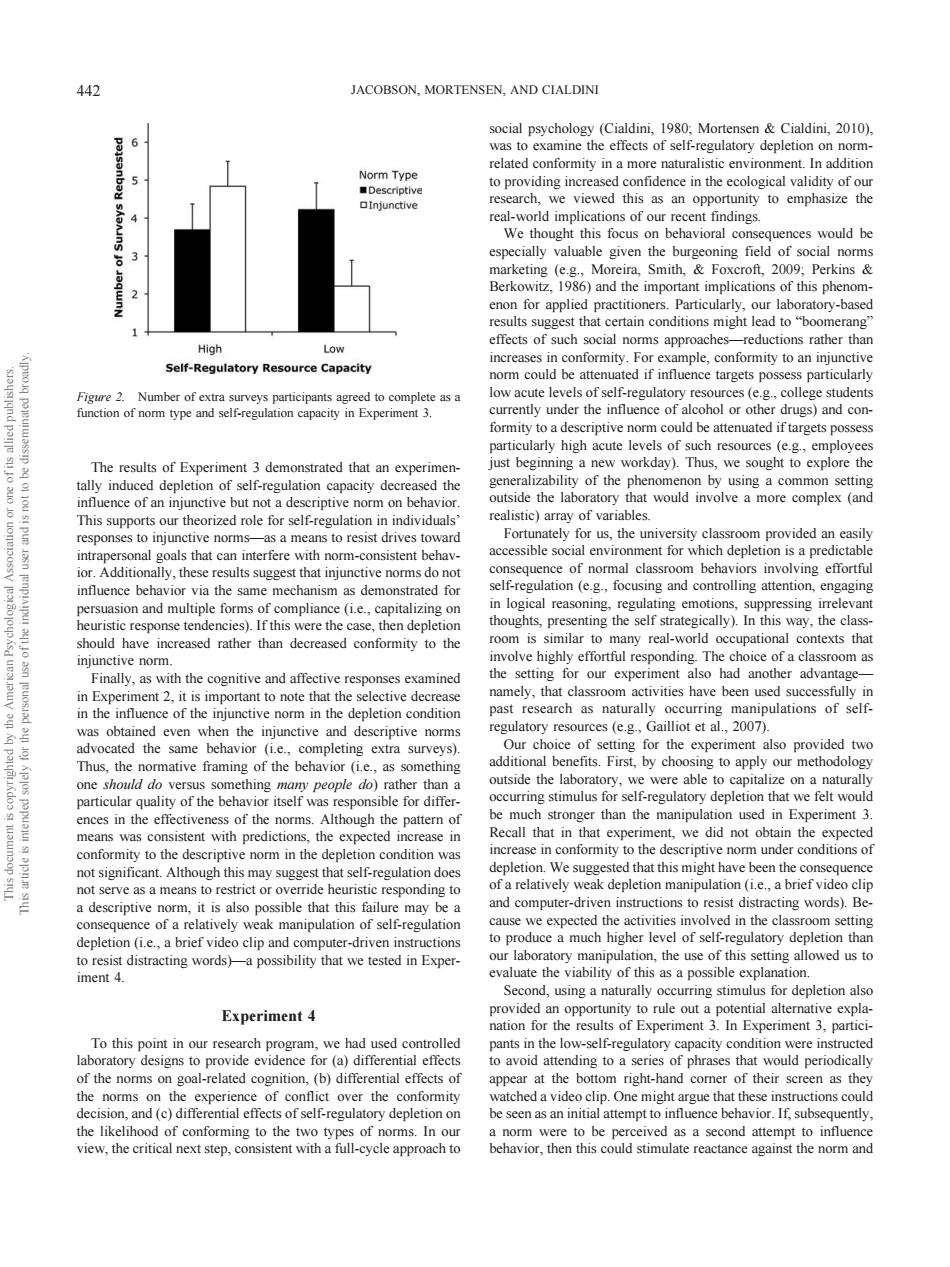

JACOBSON.MORTENSEN.AND CIALDINI 86 Norm Type related conformity in a more naturalistic en 4 方3 o for.our laboratory-base High ow Self-Regulatory Resource Capacity incre of s The results of expe ment 3 demonstrated that an rkday).Thus,we sought to explore th This esponse a the same mec as demonstrated Io onin uristie respo d haveincreased rather than ereased ontexts tha Finally,as with the cognitive and affective responses examined namely,that clas activities have been used successfully as was obtained even when the injunctive and descriptive noms for the experiment also provided tw Thus the nommative framing of the behavior as somethin by che side the lab cte e norm und sibe that this and computer-driven instructions to re racting words)B possibility that we tested in Exper ment Second,using a naturally occu Experiment 4 uscdcoatrocg of the norms on goal-related cognition.(b) ppear at the bottom right-hand comer of their screen as the opcuo o s of rms.In ate reactance against the norm and The results of Experiment 3 demonstrated that an experimentally induced depletion of self-regulation capacity decreased the influence of an injunctive but not a descriptive norm on behavior. This supports our theorized role for self-regulation in individuals’ responses to injunctive norms—as a means to resist drives toward intrapersonal goals that can interfere with norm-consistent behavior. Additionally, these results suggest that injunctive norms do not influence behavior via the same mechanism as demonstrated for persuasion and multiple forms of compliance (i.e., capitalizing on heuristic response tendencies). If this were the case, then depletion should have increased rather than decreased conformity to the injunctive norm. Finally, as with the cognitive and affective responses examined in Experiment 2, it is important to note that the selective decrease in the influence of the injunctive norm in the depletion condition was obtained even when the injunctive and descriptive norms advocated the same behavior (i.e., completing extra surveys). Thus, the normative framing of the behavior (i.e., as something one should do versus something many people do) rather than a particular quality of the behavior itself was responsible for differences in the effectiveness of the norms. Although the pattern of means was consistent with predictions, the expected increase in conformity to the descriptive norm in the depletion condition was not significant. Although this may suggest that self-regulation does not serve as a means to restrict or override heuristic responding to a descriptive norm, it is also possible that this failure may be a consequence of a relatively weak manipulation of self-regulation depletion (i.e., a brief video clip and computer-driven instructions to resist distracting words)—a possibility that we tested in Experiment 4. Experiment 4 To this point in our research program, we had used controlled laboratory designs to provide evidence for (a) differential effects of the norms on goal-related cognition, (b) differential effects of the norms on the experience of conflict over the conformity decision, and (c) differential effects of self-regulatory depletion on the likelihood of conforming to the two types of norms. In our view, the critical next step, consistent with a full-cycle approach to social psychology (Cialdini, 1980; Mortensen & Cialdini, 2010), was to examine the effects of self-regulatory depletion on normrelated conformity in a more naturalistic environment. In addition to providing increased confidence in the ecological validity of our research, we viewed this as an opportunity to emphasize the real-world implications of our recent findings. We thought this focus on behavioral consequences would be especially valuable given the burgeoning field of social norms marketing (e.g., Moreira, Smith, & Foxcroft, 2009; Perkins & Berkowitz, 1986) and the important implications of this phenomenon for applied practitioners. Particularly, our laboratory-based results suggest that certain conditions might lead to “boomerang” effects of such social norms approaches—reductions rather than increases in conformity. For example, conformity to an injunctive norm could be attenuated if influence targets possess particularly low acute levels of self-regulatory resources (e.g., college students currently under the influence of alcohol or other drugs) and conformity to a descriptive norm could be attenuated if targets possess particularly high acute levels of such resources (e.g., employees just beginning a new workday). Thus, we sought to explore the generalizability of the phenomenon by using a common setting outside the laboratory that would involve a more complex (and realistic) array of variables. Fortunately for us, the university classroom provided an easily accessible social environment for which depletion is a predictable consequence of normal classroom behaviors involving effortful self-regulation (e.g., focusing and controlling attention, engaging in logical reasoning, regulating emotions, suppressing irrelevant thoughts, presenting the self strategically). In this way, the classroom is similar to many real-world occupational contexts that involve highly effortful responding. The choice of a classroom as the setting for our experiment also had another advantage— namely, that classroom activities have been used successfully in past research as naturally occurring manipulations of selfregulatory resources (e.g., Gailliot et al., 2007). Our choice of setting for the experiment also provided two additional benefits. First, by choosing to apply our methodology outside the laboratory, we were able to capitalize on a naturally occurring stimulus for self-regulatory depletion that we felt would be much stronger than the manipulation used in Experiment 3. Recall that in that experiment, we did not obtain the expected increase in conformity to the descriptive norm under conditions of depletion. We suggested that this might have been the consequence of a relatively weak depletion manipulation (i.e., a brief video clip and computer-driven instructions to resist distracting words). Because we expected the activities involved in the classroom setting to produce a much higher level of self-regulatory depletion than our laboratory manipulation, the use of this setting allowed us to evaluate the viability of this as a possible explanation. Second, using a naturally occurring stimulus for depletion also provided an opportunity to rule out a potential alternative explanation for the results of Experiment 3. In Experiment 3, participants in the low-self-regulatory capacity condition were instructed to avoid attending to a series of phrases that would periodically appear at the bottom right-hand corner of their screen as they watched a video clip. One might argue that these instructions could be seen as an initial attempt to influence behavior. If, subsequently, a norm were to be perceived as a second attempt to influence behavior, then this could stimulate reactance against the norm and Figure 2. Number of extra surveys participants agreed to complete as a function of norm type and self-regulation capacity in Experiment 3. 442 JACOBSON, MORTENSEN, AND CIALDINI This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly