正在加载图片...

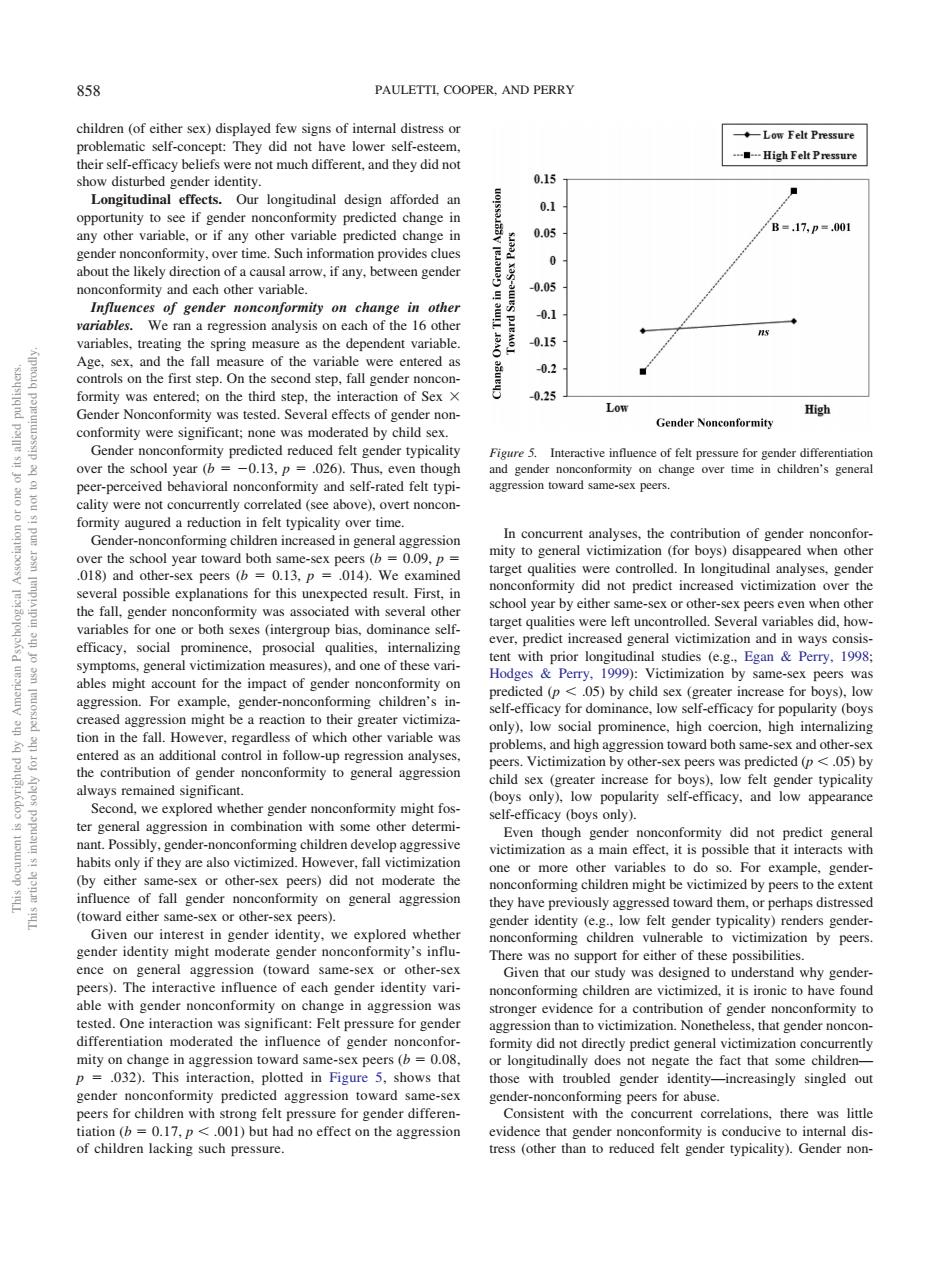

858 PAULETTL COOPER.AND PERRY 一Low Felt Pressure heir self-effic beliefs were not much different and they did no 0.15 loneitudinal design afforded an conformity predicted changein 0.1 opportunity to see if gender B=.17,p=.00 ny othe predicted c ange 0.05 bout the likely direction of a causal ar ow.fn.between gender 0 ch othe 0.05 ables. res the dependent variabl 0.15 the first step.the 0.1 o g conformity were signficant:one was moder ated by child se Gender Nonconformity nity pre active influ 013 and self-rated felt typ aggression toward same-sex peers were not cond ove non nder-nonc neral the school year to ward both ity did not chool vear by either sex or other-sex peers even when othe 1998 gene nd o fom th r increase for For exan conforming children' in y for d Ho might nce.low i ed as additiona nd high aggre ard both sm icti peers icted (p rmity general aggr ter for pop ularity sef-eficacy.and we explored wheth boy onformity might fos- ome othe r de did not only if they are alsov pe not ized by peers to the exten ard them, ed w children vu miah ard onforming children are ictimized.it is ironic to have found nt:Felt 032).This inter plouted in Figure s that hos with troubled gender identity -increasingly singled out pred der-nonconf per for abus =0.17. .001)but had no effect on the aggres sion vidence that ender nity is e to i of children lacking such pressure children (of either sex) displayed few signs of internal distress or problematic self-concept: They did not have lower self-esteem, their self-efficacy beliefs were not much different, and they did not show disturbed gender identity. Longitudinal effects. Our longitudinal design afforded an opportunity to see if gender nonconformity predicted change in any other variable, or if any other variable predicted change in gender nonconformity, over time. Such information provides clues about the likely direction of a causal arrow, if any, between gender nonconformity and each other variable. Influences of gender nonconformity on change in other variables. We ran a regression analysis on each of the 16 other variables, treating the spring measure as the dependent variable. Age, sex, and the fall measure of the variable were entered as controls on the first step. On the second step, fall gender nonconformity was entered; on the third step, the interaction of Sex Gender Nonconformity was tested. Several effects of gender nonconformity were significant; none was moderated by child sex. Gender nonconformity predicted reduced felt gender typicality over the school year (b 0.13, p .026). Thus, even though peer-perceived behavioral nonconformity and self-rated felt typicality were not concurrently correlated (see above), overt nonconformity augured a reduction in felt typicality over time. Gender-nonconforming children increased in general aggression over the school year toward both same-sex peers (b 0.09, p .018) and other-sex peers (b 0.13, p .014). We examined several possible explanations for this unexpected result. First, in the fall, gender nonconformity was associated with several other variables for one or both sexes (intergroup bias, dominance selfefficacy, social prominence, prosocial qualities, internalizing symptoms, general victimization measures), and one of these variables might account for the impact of gender nonconformity on aggression. For example, gender-nonconforming children’s increased aggression might be a reaction to their greater victimization in the fall. However, regardless of which other variable was entered as an additional control in follow-up regression analyses, the contribution of gender nonconformity to general aggression always remained significant. Second, we explored whether gender nonconformity might foster general aggression in combination with some other determinant. Possibly, gender-nonconforming children develop aggressive habits only if they are also victimized. However, fall victimization (by either same-sex or other-sex peers) did not moderate the influence of fall gender nonconformity on general aggression (toward either same-sex or other-sex peers). Given our interest in gender identity, we explored whether gender identity might moderate gender nonconformity’s influence on general aggression (toward same-sex or other-sex peers). The interactive influence of each gender identity variable with gender nonconformity on change in aggression was tested. One interaction was significant: Felt pressure for gender differentiation moderated the influence of gender nonconformity on change in aggression toward same-sex peers (b 0.08, p .032). This interaction, plotted in Figure 5, shows that gender nonconformity predicted aggression toward same-sex peers for children with strong felt pressure for gender differentiation (b 0.17, p .001) but had no effect on the aggression of children lacking such pressure. In concurrent analyses, the contribution of gender nonconformity to general victimization (for boys) disappeared when other target qualities were controlled. In longitudinal analyses, gender nonconformity did not predict increased victimization over the school year by either same-sex or other-sex peers even when other target qualities were left uncontrolled. Several variables did, however, predict increased general victimization and in ways consistent with prior longitudinal studies (e.g., Egan & Perry, 1998; Hodges & Perry, 1999): Victimization by same-sex peers was predicted (p .05) by child sex (greater increase for boys), low self-efficacy for dominance, low self-efficacy for popularity (boys only), low social prominence, high coercion, high internalizing problems, and high aggression toward both same-sex and other-sex peers. Victimization by other-sex peers was predicted (p .05) by child sex (greater increase for boys), low felt gender typicality (boys only), low popularity self-efficacy, and low appearance self-efficacy (boys only). Even though gender nonconformity did not predict general victimization as a main effect, it is possible that it interacts with one or more other variables to do so. For example, gendernonconforming children might be victimized by peers to the extent they have previously aggressed toward them, or perhaps distressed gender identity (e.g., low felt gender typicality) renders gendernonconforming children vulnerable to victimization by peers. There was no support for either of these possibilities. Given that our study was designed to understand why gendernonconforming children are victimized, it is ironic to have found stronger evidence for a contribution of gender nonconformity to aggression than to victimization. Nonetheless, that gender nonconformity did not directly predict general victimization concurrently or longitudinally does not negate the fact that some children— those with troubled gender identity—increasingly singled out gender-nonconforming peers for abuse. Consistent with the concurrent correlations, there was little evidence that gender nonconformity is conducive to internal distress (other than to reduced felt gender typicality). Gender nonFigure 5. Interactive influence of felt pressure for gender differentiation and gender nonconformity on change over time in children’s general aggression toward same-sex peers. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 858 PAULETTI, COOPER, AND PERRY����������