正在加载图片...

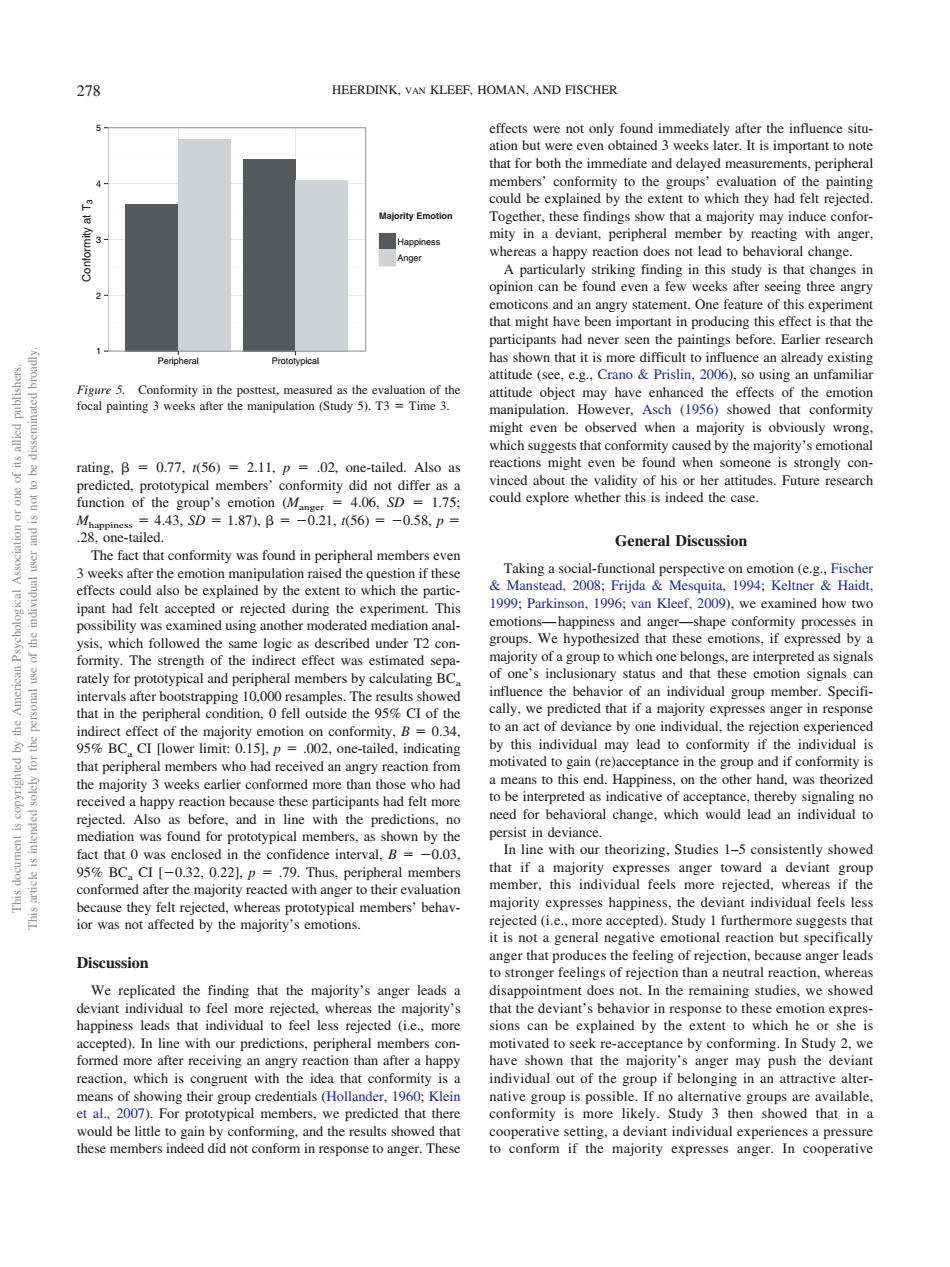

HEERDINK.VAN KLEEF.HOMAN.AND FISCHER that for both the immediate and delayed me the Majority Emotion confo ange larly striking finding in this study is that changes in stat ment.One featur xner hat ih have d is that t a isting e.g nfam conformit ailed Also as ctions might even be f and when some formity did not differ 443SD=1.87.B 021560 -058 e-tailed. General Discussion ceks after the cmotion explai d by L towhich the pa 999:Parkinson.1996:van Kleef.2009).we examined how twe ibilit was ated mediatio anal na ately for prototypical and peripheral members by calculating BC ority towhich infuence the behavior of n individual groupme anger in respor that peripheral members who had received an angry eaction from eptance in e group and if con confo had ing no rejected. before.and in lin with the BC.C1-032.0221.p hhrenhpmrhecorizingSudies1-5coasinteatyshoweg 79 hus.per whereas if the or was not affected by the majority's emotions ed)sthe individual feels it is not a ger peral negative emotionl reaction but specificall Discussion We replicated the finding that the majority's anger leads a lisappointment does not.In the remaining studies,we showed accptecdhincwi他ourpredictio con reaction.which is coneruent with the idea that conformity individual out of the s up if belonging in an attractive alter ould be lite confor eriences a pres rating, 0.77, t(56) 2.11, p .02, one-tailed. Also as predicted, prototypical members’ conformity did not differ as a function of the group’s emotion (Manger 4.06, SD 1.75; Mhappiness 4.43, SD 1.87), 0.21, t(56) 0.58, p .28, one-tailed. The fact that conformity was found in peripheral members even 3 weeks after the emotion manipulation raised the question if these effects could also be explained by the extent to which the participant had felt accepted or rejected during the experiment. This possibility was examined using another moderated mediation analysis, which followed the same logic as described under T2 conformity. The strength of the indirect effect was estimated separately for prototypical and peripheral members by calculating BCa intervals after bootstrapping 10,000 resamples. The results showed that in the peripheral condition, 0 fell outside the 95% CI of the indirect effect of the majority emotion on conformity, B 0.34, 95% BCa CI [lower limit: 0.15], p .002, one-tailed, indicating that peripheral members who had received an angry reaction from the majority 3 weeks earlier conformed more than those who had received a happy reaction because these participants had felt more rejected. Also as before, and in line with the predictions, no mediation was found for prototypical members, as shown by the fact that 0 was enclosed in the confidence interval, B 0.03, 95% BCa CI [0.32, 0.22], p .79. Thus, peripheral members conformed after the majority reacted with anger to their evaluation because they felt rejected, whereas prototypical members’ behavior was not affected by the majority’s emotions. Discussion We replicated the finding that the majority’s anger leads a deviant individual to feel more rejected, whereas the majority’s happiness leads that individual to feel less rejected (i.e., more accepted). In line with our predictions, peripheral members conformed more after receiving an angry reaction than after a happy reaction, which is congruent with the idea that conformity is a means of showing their group credentials (Hollander, 1960; Klein et al., 2007). For prototypical members, we predicted that there would be little to gain by conforming, and the results showed that these members indeed did not conform in response to anger. These effects were not only found immediately after the influence situation but were even obtained 3 weeks later. It is important to note that for both the immediate and delayed measurements, peripheral members’ conformity to the groups’ evaluation of the painting could be explained by the extent to which they had felt rejected. Together, these findings show that a majority may induce conformity in a deviant, peripheral member by reacting with anger, whereas a happy reaction does not lead to behavioral change. A particularly striking finding in this study is that changes in opinion can be found even a few weeks after seeing three angry emoticons and an angry statement. One feature of this experiment that might have been important in producing this effect is that the participants had never seen the paintings before. Earlier research has shown that it is more difficult to influence an already existing attitude (see, e.g., Crano & Prislin, 2006), so using an unfamiliar attitude object may have enhanced the effects of the emotion manipulation. However, Asch (1956) showed that conformity might even be observed when a majority is obviously wrong, which suggests that conformity caused by the majority’s emotional reactions might even be found when someone is strongly convinced about the validity of his or her attitudes. Future research could explore whether this is indeed the case. General Discussion Taking a social-functional perspective on emotion (e.g., Fischer & Manstead, 2008; Frijda & Mesquita, 1994; Keltner & Haidt, 1999; Parkinson, 1996; van Kleef, 2009), we examined how two emotions— happiness and anger—shape conformity processes in groups. We hypothesized that these emotions, if expressed by a majority of a group to which one belongs, are interpreted as signals of one’s inclusionary status and that these emotion signals can influence the behavior of an individual group member. Specifically, we predicted that if a majority expresses anger in response to an act of deviance by one individual, the rejection experienced by this individual may lead to conformity if the individual is motivated to gain (re)acceptance in the group and if conformity is a means to this end. Happiness, on the other hand, was theorized to be interpreted as indicative of acceptance, thereby signaling no need for behavioral change, which would lead an individual to persist in deviance. In line with our theorizing, Studies 1–5 consistently showed that if a majority expresses anger toward a deviant group member, this individual feels more rejected, whereas if the majority expresses happiness, the deviant individual feels less rejected (i.e., more accepted). Study 1 furthermore suggests that it is not a general negative emotional reaction but specifically anger that produces the feeling of rejection, because anger leads to stronger feelings of rejection than a neutral reaction, whereas disappointment does not. In the remaining studies, we showed that the deviant’s behavior in response to these emotion expressions can be explained by the extent to which he or she is motivated to seek re-acceptance by conforming. In Study 2, we have shown that the majority’s anger may push the deviant individual out of the group if belonging in an attractive alternative group is possible. If no alternative groups are available, conformity is more likely. Study 3 then showed that in a cooperative setting, a deviant individual experiences a pressure to conform if the majority expresses anger. In cooperative 1 2 3 4 5 Peripheral Prototypical Conformity at T3 Majority Emotion Happiness Anger Figure 5. Conformity in the posttest, measured as the evaluation of the focal painting 3 weeks after the manipulation (Study 5). T3 Time 3. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 278 HEERDINK, VAN KLEEF, HOMAN, AND FISCHER��