正在加载图片...

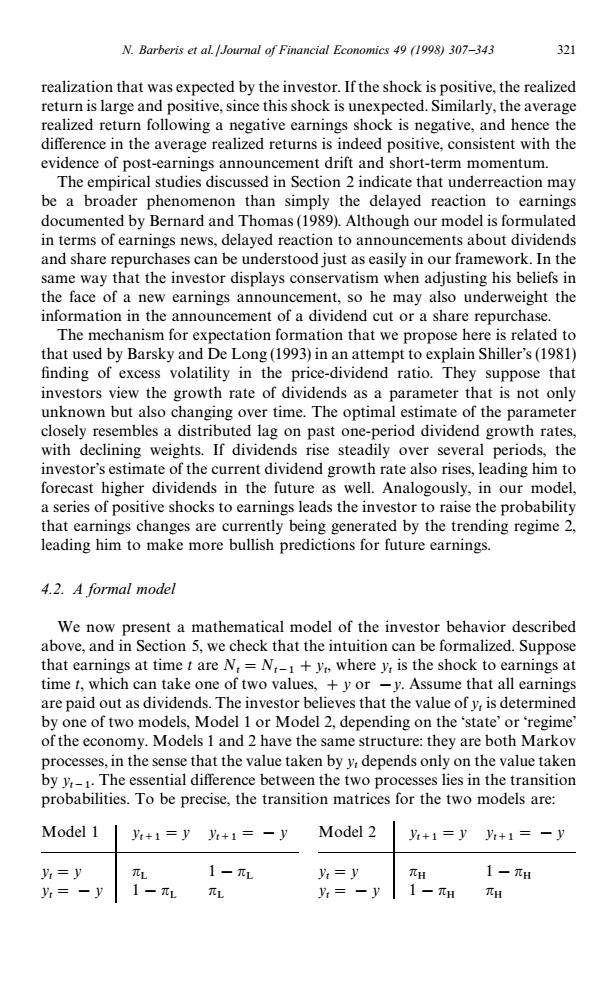

N.Barberis et al./Journal of Financial Economics 49 (1998)307-343 321 realization that was expected by the investor.If the shock is positive,the realized return is large and positive,since this shock is unexpected.Similarly,the average realized return following a negative earnings shock is negative,and hence the difference in the average realized returns is indeed positive,consistent with the evidence of post-earnings announcement drift and short-term momentum. The empirical studies discussed in Section 2 indicate that underreaction may be a broader phenomenon than simply the delayed reaction to earnings documented by Bernard and Thomas(1989).Although our model is formulated in terms of earnings news,delayed reaction to announcements about dividends and share repurchases can be understood just as easily in our framework.In the same way that the investor displays conservatism when adjusting his beliefs in the face of a new earnings announcement,so he may also underweight the information in the announcement of a dividend cut or a share repurchase. The mechanism for expectation formation that we propose here is related to that used by Barsky and De Long(1993)in an attempt to explain Shiller's(1981) finding of excess volatility in the price-dividend ratio.They suppose that investors view the growth rate of dividends as a parameter that is not only unknown but also changing over time.The optimal estimate of the parameter closely resembles a distributed lag on past one-period dividend growth rates, with declining weights.If dividends rise steadily over several periods,the investor's estimate of the current dividend growth rate also rises,leading him to forecast higher dividends in the future as well.Analogously,in our model, a series of positive shocks to earnings leads the investor to raise the probability that earnings changes are currently being generated by the trending regime 2, leading him to make more bullish predictions for future earnings. 4.2.A formal model We now present a mathematical model of the investor behavior described above,and in Section 5,we check that the intuition can be formalized.Suppose that earnings at time t are N,=N,-1+y,where y,is the shock to earnings at time t,which can take one of two values,+y or -y.Assume that all earnings are paid out as dividends.The investor believes that the value of y,is determined by one of two models,Model 1 or Model 2,depending on the 'state'or 'regime' of the economy.Models 1 and 2 have the same structure:they are both Markov processes,in the sense that the value taken by y,depends only on the value taken by y,-1.The essential difference between the two processes lies in the transition probabilities.To be precise,the transition matrices for the two models are: Model 1 y:+1=yy:+1=-y Model 2 +1=y y:+1=-y 片=y 1- yi=y πH 1-H y= 1-L πL 1-元H Hrealization that was expected by the investor. If the shock is positive, the realized return is large and positive, since this shock is unexpected. Similarly, the average realized return following a negative earnings shock is negative, and hence the difference in the average realized returns is indeed positive, consistent with the evidence of post-earnings announcement drift and short-term momentum. The empirical studies discussed in Section 2 indicate that underreaction may be a broader phenomenon than simply the delayed reaction to earnings documented by Bernard and Thomas (1989). Although our model is formulated in terms of earnings news, delayed reaction to announcements about dividends and share repurchases can be understood just as easily in our framework. In the same way that the investor displays conservatism when adjusting his beliefs in the face of a new earnings announcement, so he may also underweight the information in the announcement of a dividend cut or a share repurchase. The mechanism for expectation formation that we propose here is related to that used by Barsky and De Long (1993) in an attempt to explain Shiller’s (1981) finding of excess volatility in the price-dividend ratio. They suppose that investors view the growth rate of dividends as a parameter that is not only unknown but also changing over time. The optimal estimate of the parameter closely resembles a distributed lag on past one-period dividend growth rates, with declining weights. If dividends rise steadily over several periods, the investor’s estimate of the current dividend growth rate also rises, leading him to forecast higher dividends in the future as well. Analogously, in our model, a series of positive shocks to earnings leads the investor to raise the probability that earnings changes are currently being generated by the trending regime 2, leading him to make more bullish predictions for future earnings. 4.2. A formal model We now present a mathematical model of the investor behavior described above, and in Section 5, we check that the intuition can be formalized. Suppose that earnings at time t are Nt "Nt~1#y t , where y t is the shock to earnings at time t, which can take one of two values, #y or !y. Assume that all earnings are paid out as dividends. The investor believes that the value of y t is determined by one of two models, Model 1 or Model 2, depending on the ‘state’ or ‘regime’ of the economy. Models 1 and 2 have the same structure: they are both Markov processes, in the sense that the value taken by y t depends only on the value taken by y t~1. The essential difference between the two processes lies in the transition probabilities. To be precise, the transition matrices for the two models are: Model 1 y t`1 "y yt`1 "!y Model 2 y t`1 "y yt`1 "!y y t "y n L 1!nL y t "y n H 1!nH y t "!y 1!n L n L y t "!y 1!nH n H N. Barberis et al./Journal of Financial Economics 49 (1998) 307—343 321