正在加载图片...

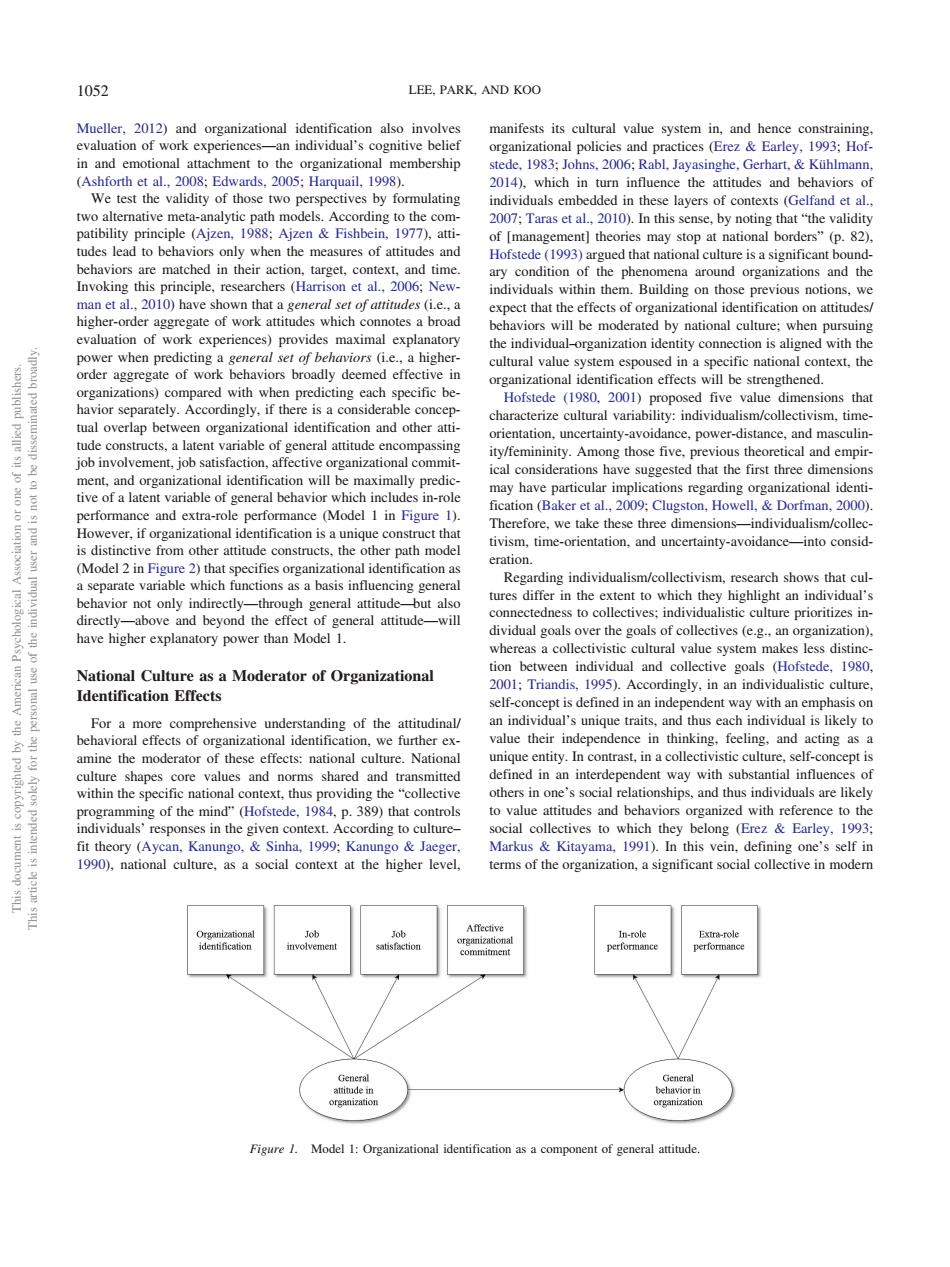

1052 LEE.PARK.AND KOO n and emotional ede 1983-Johns 2006-Rabl avasinghe Gerhant Kuhlmann ds.2005 which in turn influence the attitudes and behaviors o ording to the co e(Ajzer heec20i2ntemcnteaa8enealafamsd which conotes a broad ehaviors will be moderated by national culture:when pu the individual-organization withth ahighe Iviors bro Hofstede (1.201)proposed five value dim 即ccwemoeganoidenificaionandot rientation uncertainty-ayoida r-distance and m ment,job sat tion,affective com have particular implications regarding ication (Baker et al.,2009:Clugston.Howell.Dorfman.2000) and extra-ro ormance (Mode in Figur ration. ichpeci o which the r not only indirectly- -through general attitud indiv culture prioritizes in a collectivistic cultural yalu makes less distir e as a Moderator of Organizational dividual and collectiv Effect t is defined in an independent way with an e Cor a more nding of the attitudinal/ nique traits ach individual is likely to tity.In contrast.ina curesef-cncti ultur and norms shared and tra tted ned in an interdependent way with substar ilinnuencesoi of the m 180)thar o value attitudes and behavio to th esponses in the given context.A ording to culture- cial collectives to which they belong (Erez&Earley. 1993 Mueller, 2012) and organizational identification also involves evaluation of work experiences—an individual’s cognitive belief in and emotional attachment to the organizational membership (Ashforth et al., 2008; Edwards, 2005; Harquail, 1998). We test the validity of those two perspectives by formulating two alternative meta-analytic path models. According to the compatibility principle (Ajzen, 1988; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977), attitudes lead to behaviors only when the measures of attitudes and behaviors are matched in their action, target, context, and time. Invoking this principle, researchers (Harrison et al., 2006; Newman et al., 2010) have shown that a general set of attitudes (i.e., a higher-order aggregate of work attitudes which connotes a broad evaluation of work experiences) provides maximal explanatory power when predicting a general set of behaviors (i.e., a higherorder aggregate of work behaviors broadly deemed effective in organizations) compared with when predicting each specific behavior separately. Accordingly, if there is a considerable conceptual overlap between organizational identification and other attitude constructs, a latent variable of general attitude encompassing job involvement, job satisfaction, affective organizational commitment, and organizational identification will be maximally predictive of a latent variable of general behavior which includes in-role performance and extra-role performance (Model 1 in Figure 1). However, if organizational identification is a unique construct that is distinctive from other attitude constructs, the other path model (Model 2 in Figure 2) that specifies organizational identification as a separate variable which functions as a basis influencing general behavior not only indirectly—through general attitude—but also directly—above and beyond the effect of general attitude—will have higher explanatory power than Model 1. National Culture as a Moderator of Organizational Identification Effects For a more comprehensive understanding of the attitudinal/ behavioral effects of organizational identification, we further examine the moderator of these effects: national culture. National culture shapes core values and norms shared and transmitted within the specific national context, thus providing the “collective programming of the mind” (Hofstede, 1984, p. 389) that controls individuals’ responses in the given context. According to culture– fit theory (Aycan, Kanungo, & Sinha, 1999; Kanungo & Jaeger, 1990), national culture, as a social context at the higher level, manifests its cultural value system in, and hence constraining, organizational policies and practices (Erez & Earley, 1993; Hofstede, 1983; Johns, 2006; Rabl, Jayasinghe, Gerhart, & Kühlmann, 2014), which in turn influence the attitudes and behaviors of individuals embedded in these layers of contexts (Gelfand et al., 2007; Taras et al., 2010). In this sense, by noting that “the validity of [management] theories may stop at national borders” (p. 82), Hofstede (1993) argued that national culture is a significant boundary condition of the phenomena around organizations and the individuals within them. Building on those previous notions, we expect that the effects of organizational identification on attitudes/ behaviors will be moderated by national culture; when pursuing the individual–organization identity connection is aligned with the cultural value system espoused in a specific national context, the organizational identification effects will be strengthened. Hofstede (1980, 2001) proposed five value dimensions that characterize cultural variability: individualism/collectivism, timeorientation, uncertainty-avoidance, power-distance, and masculinity/femininity. Among those five, previous theoretical and empirical considerations have suggested that the first three dimensions may have particular implications regarding organizational identification (Baker et al., 2009; Clugston, Howell, & Dorfman, 2000). Therefore, we take these three dimensions—individualism/collectivism, time-orientation, and uncertainty-avoidance—into consideration. Regarding individualism/collectivism, research shows that cultures differ in the extent to which they highlight an individual’s connectedness to collectives; individualistic culture prioritizes individual goals over the goals of collectives (e.g., an organization), whereas a collectivistic cultural value system makes less distinction between individual and collective goals (Hofstede, 1980, 2001; Triandis, 1995). Accordingly, in an individualistic culture, self-concept is defined in an independent way with an emphasis on an individual’s unique traits, and thus each individual is likely to value their independence in thinking, feeling, and acting as a unique entity. In contrast, in a collectivistic culture, self-concept is defined in an interdependent way with substantial influences of others in one’s social relationships, and thus individuals are likely to value attitudes and behaviors organized with reference to the social collectives to which they belong (Erez & Earley, 1993; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In this vein, defining one’s self in terms of the organization, a significant social collective in modern Figure 1. Model 1: Organizational identification as a component of general attitude. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 1052 LEE, PARK, AND KOO