正在加载图片...

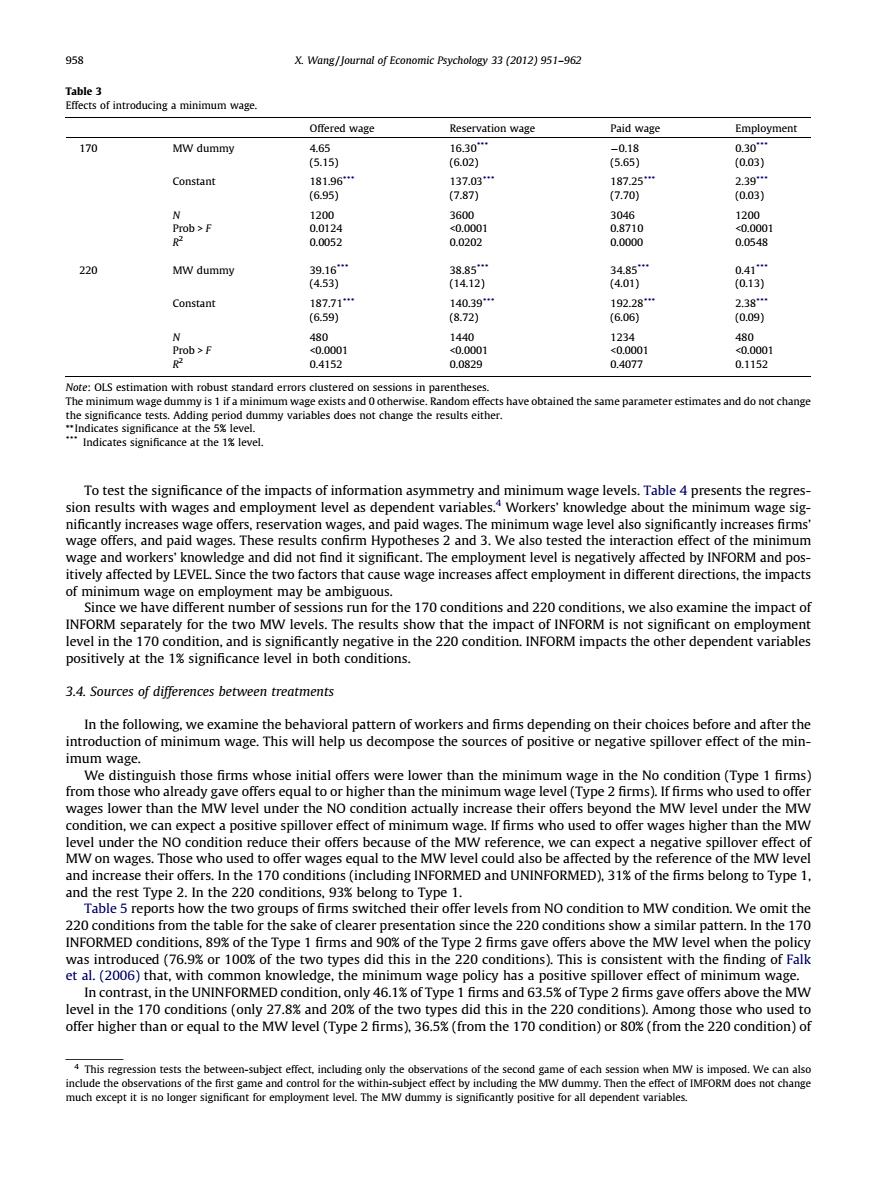

958 X.Wang/Journal of Economic Psychology 33(2012)951-962 m wage Offer dwa起 Paid wag Employment 170 MW dummy 60 665 (0.3 Constant (287 (0.03) 脱 微 220 MWdummy Constant 87 199 806 Nore:OLS estimation with robust standard errors clustered on sessions in parentheses a m have obtained the sme para meter estin and do no chang ange the results either. at the 5%level. To test the ificance of the impac s of info nts the WiConcra55W2geoierncenationwage5andpaidwagshemwinmwaeeleelalsosiegicantyncteascsfms wage and workers'kr edge and did not find it significant.The employment level is negatively affected by INFORM and pos ely affected by LEVEL nce the two factors that cause wage increases affect employment in different directions.the impacts Since we have different numbe fy0sSionsnorthe170conditionsand20condiionsweaboeaminetheimpactof MW The result positively at the sigficance level in both conditions. 3.4.Sources of differences betw een treatments imum wage. from wages lower than the MW level under the NO condition actually increase their offers beyond the MW level under the MW nrms wno M MW refe MW on wages Tho who L offer wages eq the m belna to. of the MW leve offer levels from NOc onditiontoMWcondionwenormttg 20 (7 of the two types did this in the 2)This is with the finding of Falk n it is n To test the significance of the impacts of information asymmetry and minimum wage levels. Table 4 presents the regression results with wages and employment level as dependent variables.4 Workers’ knowledge about the minimum wage significantly increases wage offers, reservation wages, and paid wages. The minimum wage level also significantly increases firms’ wage offers, and paid wages. These results confirm Hypotheses 2 and 3. We also tested the interaction effect of the minimum wage and workers’ knowledge and did not find it significant. The employment level is negatively affected by INFORM and positively affected by LEVEL. Since the two factors that cause wage increases affect employment in different directions, the impacts of minimum wage on employment may be ambiguous. Since we have different number of sessions run for the 170 conditions and 220 conditions, we also examine the impact of INFORM separately for the two MW levels. The results show that the impact of INFORM is not significant on employment level in the 170 condition, and is significantly negative in the 220 condition. INFORM impacts the other dependent variables positively at the 1% significance level in both conditions. 3.4. Sources of differences between treatments In the following, we examine the behavioral pattern of workers and firms depending on their choices before and after the introduction of minimum wage. This will help us decompose the sources of positive or negative spillover effect of the minimum wage. We distinguish those firms whose initial offers were lower than the minimum wage in the No condition (Type 1 firms) from those who already gave offers equal to or higher than the minimum wage level (Type 2 firms). If firms who used to offer wages lower than the MW level under the NO condition actually increase their offers beyond the MW level under the MW condition, we can expect a positive spillover effect of minimum wage. If firms who used to offer wages higher than the MW level under the NO condition reduce their offers because of the MW reference, we can expect a negative spillover effect of MW on wages. Those who used to offer wages equal to the MW level could also be affected by the reference of the MW level and increase their offers. In the 170 conditions (including INFORMED and UNINFORMED), 31% of the firms belong to Type 1, and the rest Type 2. In the 220 conditions, 93% belong to Type 1. Table 5 reports how the two groups of firms switched their offer levels from NO condition to MW condition. We omit the 220 conditions from the table for the sake of clearer presentation since the 220 conditions show a similar pattern. In the 170 INFORMED conditions, 89% of the Type 1 firms and 90% of the Type 2 firms gave offers above the MW level when the policy was introduced (76.9% or 100% of the two types did this in the 220 conditions). This is consistent with the finding of Falk et al. (2006) that, with common knowledge, the minimum wage policy has a positive spillover effect of minimum wage. In contrast, in the UNINFORMED condition, only 46.1% of Type 1 firms and 63.5% of Type 2 firms gave offers above the MW level in the 170 conditions (only 27.8% and 20% of the two types did this in the 220 conditions). Among those who used to offer higher than or equal to the MW level (Type 2 firms), 36.5% (from the 170 condition) or 80% (from the 220 condition) of Table 3 Effects of introducing a minimum wage. Offered wage Reservation wage Paid wage Employment 170 MW dummy 4.65 16.30*** 0.18 0.30*** (5.15) (6.02) (5.65) (0.03) Constant 181.96*** 137.03*** 187.25*** 2.39*** (6.95) (7.87) (7.70) (0.03) N 1200 3600 3046 1200 Prob > F 0.0124 <0.0001 0.8710 <0.0001 R2 0.0052 0.0202 0.0000 0.0548 220 MW dummy 39.16*** 38.85*** 34.85*** 0.41*** (4.53) (14.12) (4.01) (0.13) Constant 187.71*** 140.39*** 192.28*** 2.38*** (6.59) (8.72) (6.06) (0.09) N 480 1440 1234 480 Prob > F <0.0001 <0.0001 <0.0001 <0.0001 R2 0.4152 0.0829 0.4077 0.1152 Note: OLS estimation with robust standard errors clustered on sessions in parentheses. The minimum wage dummy is 1 if a minimum wage exists and 0 otherwise. Random effects have obtained the same parameter estimates and do not change the significance tests. Adding period dummy variables does not change the results either. ⁄⁄ Indicates significance at the 5% level. *** Indicates significance at the 1% level. 4 This regression tests the between-subject effect, including only the observations of the second game of each session when MW is imposed. We can also include the observations of the first game and control for the within-subject effect by including the MW dummy. Then the effect of IMFORM does not change much except it is no longer significant for employment level. The MW dummy is significantly positive for all dependent variables. 958 X. Wang / Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2012) 951–962�