正在加载图片...

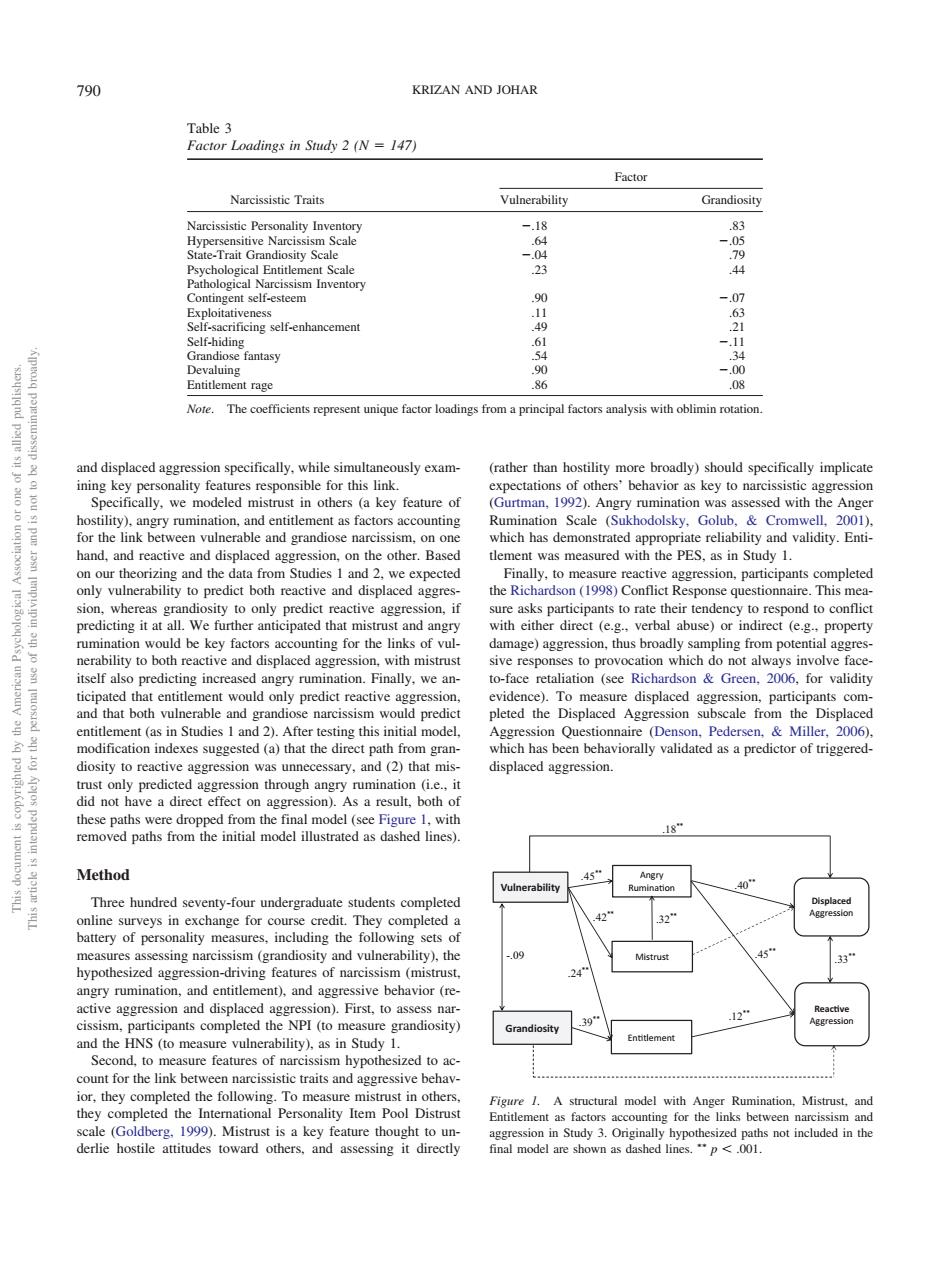

790 KRIZAN AND JOHAR Table3 Factor Loadings in Sudy 2 (N=147) Narcissistic Traits Vulnerability sity S l Entit Scale 44 ent self-esteem self-enhancemer 14 el fantasy Entitlement rage isly exam- cally e mistrust in others (a key feat sed with the een vulne able and grandiose r issism,on one ete nery rumination.Finally.we an nmcnwoulaoapretircactiveasgresio ent (as in Studies I and2).After stine this initial model n.Pedersen. Miller.2006). sted (a)that the direct pat angry ruminati n (ie..i ave a direct en As a removed paths from the initial model illustrated as dashed lines) Method Three hundred seventy-four undergraduate students completed ngry rumination and entitlement)and aggressive behavior (re nd the HNS (to me nt for the link be e features zed to a To measure ral model with g for derlie hostile attitudes toward others,and assessing it directly inal model are shown as dashed linespand displaced aggression specifically, while simultaneously examining key personality features responsible for this link. Specifically, we modeled mistrust in others (a key feature of hostility), angry rumination, and entitlement as factors accounting for the link between vulnerable and grandiose narcissism, on one hand, and reactive and displaced aggression, on the other. Based on our theorizing and the data from Studies 1 and 2, we expected only vulnerability to predict both reactive and displaced aggression, whereas grandiosity to only predict reactive aggression, if predicting it at all. We further anticipated that mistrust and angry rumination would be key factors accounting for the links of vulnerability to both reactive and displaced aggression, with mistrust itself also predicting increased angry rumination. Finally, we anticipated that entitlement would only predict reactive aggression, and that both vulnerable and grandiose narcissism would predict entitlement (as in Studies 1 and 2). After testing this initial model, modification indexes suggested (a) that the direct path from grandiosity to reactive aggression was unnecessary, and (2) that mistrust only predicted aggression through angry rumination (i.e., it did not have a direct effect on aggression). As a result, both of these paths were dropped from the final model (see Figure 1, with removed paths from the initial model illustrated as dashed lines). Method Three hundred seventy-four undergraduate students completed online surveys in exchange for course credit. They completed a battery of personality measures, including the following sets of measures assessing narcissism (grandiosity and vulnerability), the hypothesized aggression-driving features of narcissism (mistrust, angry rumination, and entitlement), and aggressive behavior (reactive aggression and displaced aggression). First, to assess narcissism, participants completed the NPI (to measure grandiosity) and the HNS (to measure vulnerability), as in Study 1. Second, to measure features of narcissism hypothesized to account for the link between narcissistic traits and aggressive behavior, they completed the following. To measure mistrust in others, they completed the International Personality Item Pool Distrust scale (Goldberg, 1999). Mistrust is a key feature thought to underlie hostile attitudes toward others, and assessing it directly (rather than hostility more broadly) should specifically implicate expectations of others’ behavior as key to narcissistic aggression (Gurtman, 1992). Angry rumination was assessed with the Anger Rumination Scale (Sukhodolsky, Golub, & Cromwell, 2001), which has demonstrated appropriate reliability and validity. Entitlement was measured with the PES, as in Study 1. Finally, to measure reactive aggression, participants completed the Richardson (1998) Conflict Response questionnaire. This measure asks participants to rate their tendency to respond to conflict with either direct (e.g., verbal abuse) or indirect (e.g., property damage) aggression, thus broadly sampling from potential aggressive responses to provocation which do not always involve faceto-face retaliation (see Richardson & Green, 2006, for validity evidence). To measure displaced aggression, participants completed the Displaced Aggression subscale from the Displaced Aggression Questionnaire (Denson, Pedersen, & Miller, 2006), which has been behaviorally validated as a predictor of triggereddisplaced aggression. Table 3 Factor Loadings in Study 2 (N 147) Narcissistic Traits Factor Vulnerability Grandiosity Narcissistic Personality Inventory .18 .83 Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale .64 .05 State-Trait Grandiosity Scale .04 .79 Psychological Entitlement Scale .23 .44 Pathological Narcissism Inventory Contingent self-esteem .90 .07 Exploitativeness .11 .63 Self-sacrificing self-enhancement .49 .21 Self-hiding .61 .11 Grandiose fantasy .54 .34 Devaluing .90 .00 Entitlement rage .86 .08 Note. The coefficients represent unique factor loadings from a principal factors analysis with oblimin rotation. Grandiosity Vulnerability Entlement Mistrust Angry Ruminaon Displaced Aggression Reacve Aggression .18** .45** .42** .32** .24** .39** .12** .40** .45** .33 -.09 ** Figure 1. A structural model with Anger Rumination, Mistrust, and Entitlement as factors accounting for the links between narcissism and aggression in Study 3. Originally hypothesized paths not included in the final model are shown as dashed lines. p .001. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 790 KRIZAN AND JOHAR������������