正在加载图片...

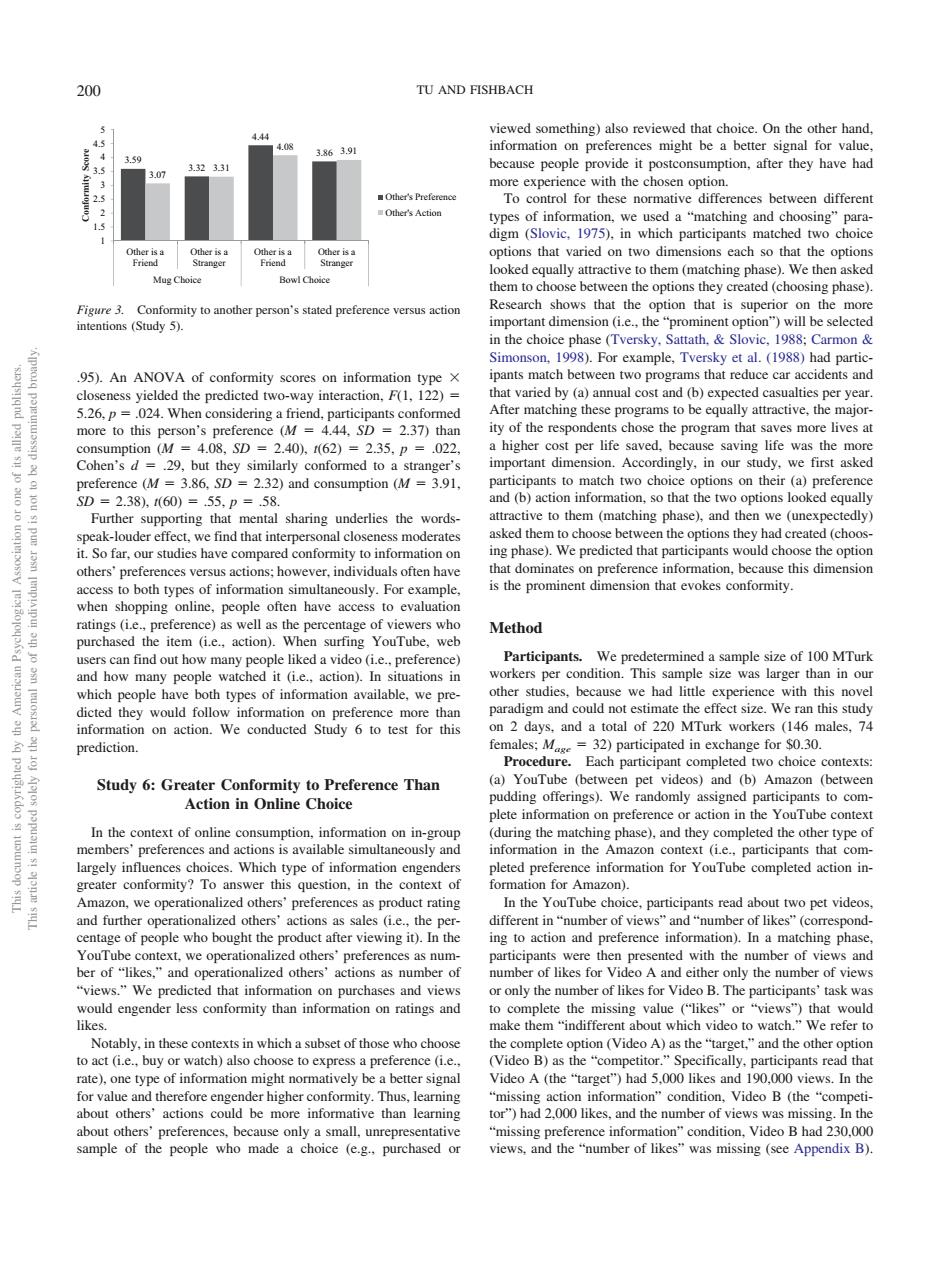

200 TU AND FISHBACH vewed something)aso that choice.O hand. 3.9 people tconsumption.after they have had exp ol for th of information,we used o Choice earch shows that the o ior on the mo ace car acc cnts an d two-way interaction,F1.1 Cohen's 29.but the similarly conformed to a stra Accordingly.in ou aske (M Further mental sharing underlies the words ttractive to them (matching phase).and then we s moderat perce Method can find out how ma ference .e-,action ther dicted they would than on action o 220 MTurk emales; text Study 6:Greater Confo rmity to Preference Than Action in Online Choice In the context of online ption.information on in-gro nformation in the conformity?To an tion,in the context of we operatio as prod n the YouTube ch cad ab o pet video ation).In a matching phase "and on views."We predicted that information on purchases and views or only the number of likes for Video B.The participants'task wa d engender less conformity than inf which a subet of VideoA (the"targe)had 5.000 likes and 190.000 views.In the condition Video B(the" bout oth rence inform sample of the people who (purchased or the"umber of likes' was missing (see Appendix B) .95). An ANOVA of conformity scores on information type closeness yielded the predicted two-way interaction, F(1, 122) 5.26, p .024. When considering a friend, participants conformed more to this person’s preference (M 4.44, SD 2.37) than consumption (M 4.08, SD 2.40), t(62) 2.35, p .022, Cohen’s d .29, but they similarly conformed to a stranger’s preference (M 3.86, SD 2.32) and consumption (M 3.91, SD 2.38), t(60) .55, p .58. Further supporting that mental sharing underlies the wordsspeak-louder effect, we find that interpersonal closeness moderates it. So far, our studies have compared conformity to information on others’ preferences versus actions; however, individuals often have access to both types of information simultaneously. For example, when shopping online, people often have access to evaluation ratings (i.e., preference) as well as the percentage of viewers who purchased the item (i.e., action). When surfing YouTube, web users can find out how many people liked a video (i.e., preference) and how many people watched it (i.e., action). In situations in which people have both types of information available, we predicted they would follow information on preference more than information on action. We conducted Study 6 to test for this prediction. Study 6: Greater Conformity to Preference Than Action in Online Choice In the context of online consumption, information on in-group members’ preferences and actions is available simultaneously and largely influences choices. Which type of information engenders greater conformity? To answer this question, in the context of Amazon, we operationalized others’ preferences as product rating and further operationalized others’ actions as sales (i.e., the percentage of people who bought the product after viewing it). In the YouTube context, we operationalized others’ preferences as number of “likes,” and operationalized others’ actions as number of “views.” We predicted that information on purchases and views would engender less conformity than information on ratings and likes. Notably, in these contexts in which a subset of those who choose to act (i.e., buy or watch) also choose to express a preference (i.e., rate), one type of information might normatively be a better signal for value and therefore engender higher conformity. Thus, learning about others’ actions could be more informative than learning about others’ preferences, because only a small, unrepresentative sample of the people who made a choice (e.g., purchased or viewed something) also reviewed that choice. On the other hand, information on preferences might be a better signal for value, because people provide it postconsumption, after they have had more experience with the chosen option. To control for these normative differences between different types of information, we used a “matching and choosing” paradigm (Slovic, 1975), in which participants matched two choice options that varied on two dimensions each so that the options looked equally attractive to them (matching phase). We then asked them to choose between the options they created (choosing phase). Research shows that the option that is superior on the more important dimension (i.e., the “prominent option”) will be selected in the choice phase (Tversky, Sattath, & Slovic, 1988; Carmon & Simonson, 1998). For example, Tversky et al. (1988) had participants match between two programs that reduce car accidents and that varied by (a) annual cost and (b) expected casualties per year. After matching these programs to be equally attractive, the majority of the respondents chose the program that saves more lives at a higher cost per life saved, because saving life was the more important dimension. Accordingly, in our study, we first asked participants to match two choice options on their (a) preference and (b) action information, so that the two options looked equally attractive to them (matching phase), and then we (unexpectedly) asked them to choose between the options they had created (choosing phase). We predicted that participants would choose the option that dominates on preference information, because this dimension is the prominent dimension that evokes conformity. Method Participants. We predetermined a sample size of 100 MTurk workers per condition. This sample size was larger than in our other studies, because we had little experience with this novel paradigm and could not estimate the effect size. We ran this study on 2 days, and a total of 220 MTurk workers (146 males, 74 females; Mage 32) participated in exchange for $0.30. Procedure. Each participant completed two choice contexts: (a) YouTube (between pet videos) and (b) Amazon (between pudding offerings). We randomly assigned participants to complete information on preference or action in the YouTube context (during the matching phase), and they completed the other type of information in the Amazon context (i.e., participants that completed preference information for YouTube completed action information for Amazon). In the YouTube choice, participants read about two pet videos, different in “number of views” and “number of likes” (corresponding to action and preference information). In a matching phase, participants were then presented with the number of views and number of likes for Video A and either only the number of views or only the number of likes for Video B. The participants’ task was to complete the missing value (“likes” or “views”) that would make them “indifferent about which video to watch.” We refer to the complete option (Video A) as the “target,” and the other option (Video B) as the “competitor.” Specifically, participants read that Video A (the “target”) had 5,000 likes and 190,000 views. In the “missing action information” condition, Video B (the “competitor”) had 2,000 likes, and the number of views was missing. In the “missing preference information” condition, Video B had 230,000 views, and the “number of likes” was missing (see Appendix B). 3.59 3.32 4.44 3.86 3.07 3.31 4.08 3.91 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4.5 5 Other is a Friend Other is a Stranger Other is a Friend Other is a Stranger Mug Choice Bowl Choice Conformity Score Other's Preference Other's Action Figure 3. Conformity to another person’s stated preference versus action intentions (Study 5). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 200 TU AND FISHBACH����������������