正在加载图片...

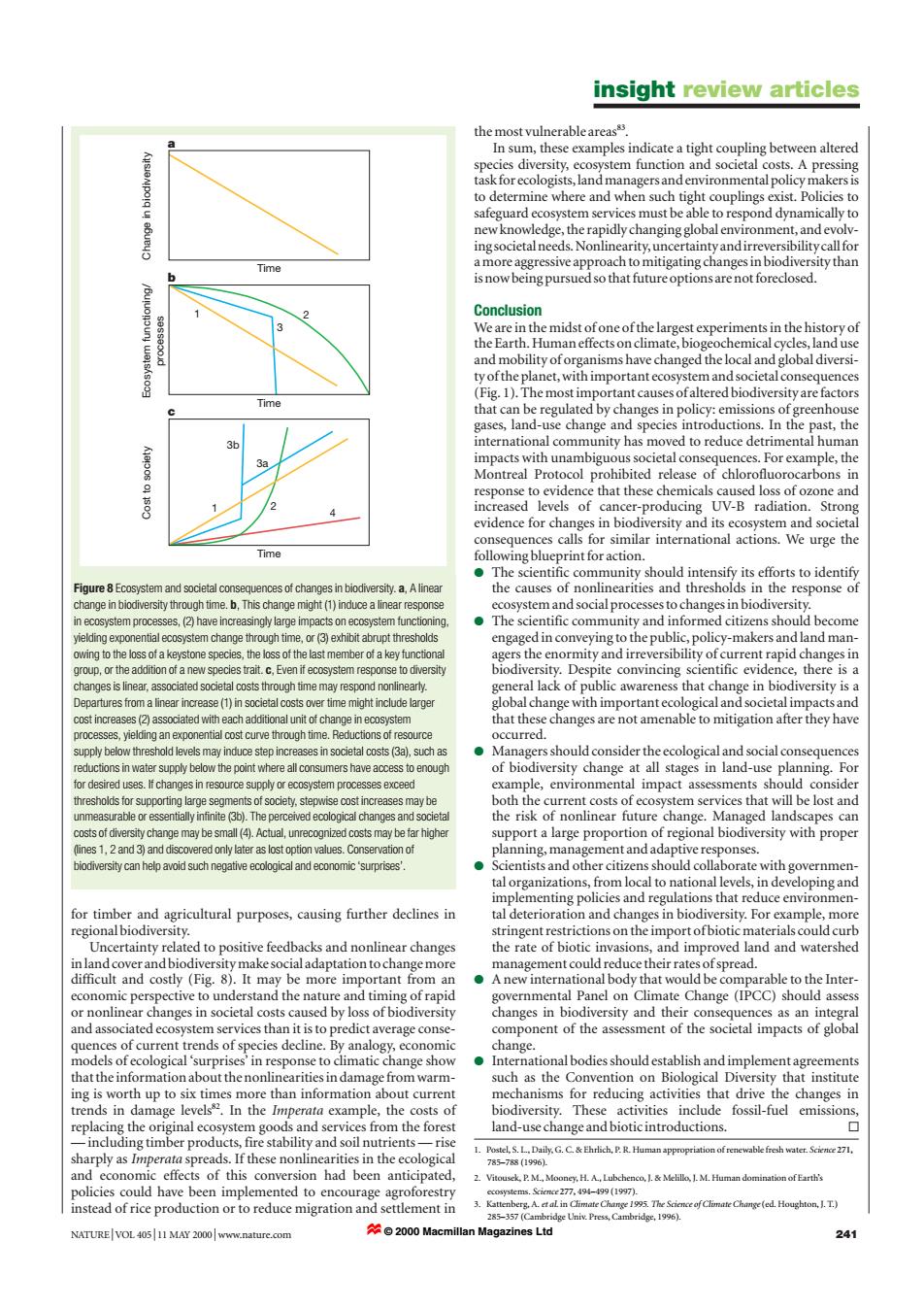

insight review articles the most vulnerableareas In sum,these examples indicate a tight coupling between altered species diversity,ecosystem function and societal costs.A pressing task for ecologists,land managers and environmental policy makers is to determine where and when such tight couplings exist.Policies to safeguard ecosystem services must be able to respond dynamically to new knowledge,the rapidly changing global environment,and evolv- ingsocietal needs.Nonlinearity,uncertainty andirreversibilitycall for Time a more aggressive approach to mitigating changes in biodiversity than is now being pursued so that future options are not foreclosed. Conclusion We are in the midst ofone of the largest experiments in the history of the Earth.Human effects on climate,biogeochemical cycles,land use and mobility oforganisms have changed the local and global diversi- ty ofthe planet,with important ecosystem and societal consequences (Fig.1).The most important causesofalteredbiodiversityare factors Time that can be regulated by changes in policy:emissions of greenhouse gases,land-use change and species introductions.In the past,the international community has moved to reduce detrimental human impacts with unambiguous societal consequences.For example,the Montreal Protocol prohibited release of chlorofluorocarbons in response to evidence that these chemicals caused loss of ozone and increased levels of cancer-producing UV-B radiation.Strong evidence for changes in biodiversity and its ecosystem and societal consequences calls for similar international actions.We urge the Time following blueprint for action. The scientific community should intensify its efforts to identify Figure 8 Ecosystem and societal consequences of changes in biodiversity.a,A linear the causes of nonlinearities and thresholds in the response of change in biodiversity through time.b,This change might(1)induce a linear response ecosystem and social processes to changes in biodiversity. in ecosystem processes,(2)have increasingly large impacts on ecosystem functioning, The scientific community and informed citizens should become yielding exponential ecosystem change through time,or(3)exhibit abrupt thresholds engaged in conveying to the public,policy-makers and land man- owing to the loss of a keystone species,the loss of the last member of a key functional agers the enormity and irreversibility of current rapid changes in group,or the addition of a new species trait.c.Even if ecosystem response to diversity biodiversity.Despite convincing scientific evidence,there is a changes is linear,associated societal costs through time may respond nonlinearly. general lack of public awareness that change in biodiversity is a Departures from a linear increase(1)in societal costs over time might include larger global change with important ecological and societal impacts and cost increases(2)associated with each additional unit of change in ecosystem that these changes are not amenable to mitigation after they have processes,yielding an exponential cost curve through time.Reductions of resource occurred. supply below threshold levels may induce step increases in societal costs(3a),such as Managers should consider the ecological and social consequences reductions in water supply below the point where all consumers have aocess to enough of biodiversity change at all stages in land-use planning.For for desired uses.If changes in resource supply or ecosystem processes exceed example,environmental impact assessments should consider thresholds for supporting large segments of society,stepwise cost increases may be both the current costs of ecosystem services that will be lost and unmeasurable or essentially infinite (3b).The perceived ecological changes and societal the risk of nonlinear future change.Managed landscapes can costs of diversity change may be small(4).Actual,unrecognized costs may be far higher support a large proportion of regional biodiversity with proper (ines 1,2 and 3)and discovered only later as lost option values.Conservation of planning,management and adaptive responses. biodiversity can help avoid such negative ecological and economic'surprises' Scientists and other citizens should collaborate with governmen- tal organizations,from local to national levels,in developing and implementing policies and regulations that reduce environmen- for timber and agricultural purposes,causing further declines in tal deterioration and changes in biodiversity.For example,more regional biodiversity. stringent restrictions on the import ofbiotic materials could curb Uncertainty related to positive feedbacks and nonlinear changes the rate of biotic invasions,and improved land and watershed in land cover and biodiversity make social adaptation to change more management could reduce their rates ofspread. difficult and costly(Fig.8).It may be more important from an ● A new international body that would be comparable to the Inter- economic perspective to understand the nature and timing of rapid governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)should assess or nonlinear changes in societal costs caused by loss of biodiversity changes in biodiversity and their consequences as an integral and associated ecosystem services than it is to predict average conse- component of the assessment of the societal impacts of global quences of current trends of species decline.By analogy,economic change. models of ecological 'surprises'in response to climatic change show Internationalbodies should establish andimplement agreements that the information about the nonlinearities in damage from warm- such as the Convention on Biological Diversity that institute ing is worth up to six times more than information about current mechanisms for reducing activities that drive the changes in trends in damage levels.In the Imperata example,the costs of biodiversity.These activities include fossil-fuel emissions, replacing the original ecosystem goods and services from the forest land-use change and biotic introductions. Q -including timber products,fire stability and soil nutrients- -rise 1.Postel,S.L.Daily,G.C.&Ehrlich,P.R.Human appropriation of renewable fresh water.Science 271. sharply as Imperata spreads.If these nonlinearities in the ecological 785-788119961. and economic effects of this conversion had been anticipated, 2.Vitousek,P.M.,Mooney,H.A.,Lubchenco,).Melillo,)M.Human domination of Farth's policies could have been implemented to encourage agroforestry ecosystems.Science277,494-499(1997). instead of rice production or to reduce migration and settlement in 3.Kattenberg.A.etal in Climate Change 1995.The Science ofClimate Change(ed.Houghton,I.T.) 285-357(Cambridge Univ.Press,Cambridge,1996). NATURE|VOL 40511 MAY 2000 www.nature.com 2000 Macmillan Magazines Ltd 241for timber and agricultural purposes, causing further declines in regional biodiversity. Uncertainty related to positive feedbacks and nonlinear changes in land cover and biodiversity make social adaptation to change more difficult and costly (Fig. 8). It may be more important from an economic perspective to understand the nature and timing of rapid or nonlinear changes in societal costs caused by loss of biodiversity and associated ecosystem services than it is to predict average consequences of current trends of species decline. By analogy, economic models of ecological ‘surprises’ in response to climatic change show that the information about the nonlinearities in damage from warming is worth up to six times more than information about current trends in damage levels82. In the Imperata example, the costs of replacing the original ecosystem goods and services from the forest — including timber products, fire stability and soil nutrients — rise sharply as Imperata spreads. If these nonlinearities in the ecological and economic effects of this conversion had been anticipated, policies could have been implemented to encourage agroforestry instead of rice production or to reduce migration and settlement in the most vulnerable areas83. In sum, these examples indicate a tight coupling between altered species diversity, ecosystem function and societal costs. A pressing task for ecologists, land managers and environmental policy makers is to determine where and when such tight couplings exist. Policies to safeguard ecosystem services must be able to respond dynamically to new knowledge, the rapidly changing global environment, and evolving societal needs. Nonlinearity, uncertainty and irreversibility call for a more aggressive approach to mitigating changes in biodiversity than is now being pursued so that future options are not foreclosed. Conclusion We are in the midst of one of the largest experiments in the history of the Earth. Human effects on climate, biogeochemical cycles, land use and mobility of organisms have changed the local and global diversity of the planet, with important ecosystem and societal consequences (Fig. 1). The most important causes of altered biodiversity are factors that can be regulated by changes in policy: emissions of greenhouse gases, land-use change and species introductions. In the past, the international community has moved to reduce detrimental human impacts with unambiguous societal consequences. For example, the Montreal Protocol prohibited release of chlorofluorocarbons in response to evidence that these chemicals caused loss of ozone and increased levels of cancer-producing UV-B radiation. Strong evidence for changes in biodiversity and its ecosystem and societal consequences calls for similar international actions. We urge the following blueprint for action. ● The scientific community should intensify its efforts to identify the causes of nonlinearities and thresholds in the response of ecosystem and social processes to changes in biodiversity. ● The scientific community and informed citizens should become engaged in conveying to the public, policy-makers and land managers the enormity and irreversibility of current rapid changes in biodiversity. Despite convincing scientific evidence, there is a general lack of public awareness that change in biodiversity is a global change with important ecological and societal impacts and that these changes are not amenable to mitigation after they have occurred. ● Managers should consider the ecological and social consequences of biodiversity change at all stages in land-use planning. For example, environmental impact assessments should consider both the current costs of ecosystem services that will be lost and the risk of nonlinear future change. Managed landscapes can support a large proportion of regional biodiversity with proper planning, management and adaptive responses. ● Scientists and other citizens should collaborate with governmental organizations, from local to national levels, in developing and implementing policies and regulations that reduce environmental deterioration and changes in biodiversity. For example, more stringent restrictions on the import of biotic materials could curb the rate of biotic invasions, and improved land and watershed management could reduce their rates of spread. ● A new international body that would be comparable to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) should assess changes in biodiversity and their consequences as an integral component of the assessment of the societal impacts of global change. ● International bodies should establish and implement agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity that institute mechanisms for reducing activities that drive the changes in biodiversity. These activities include fossil-fuel emissions, land-use change and biotic introductions. ■ 1. Postel, S. L., Daily, G. C. & Ehrlich, P. R. Human appropriation of renewable fresh water. Science 271, 785–788 (1996). 2. Vitousek, P. M., Mooney, H. A., Lubchenco, J. & Melillo, J. M. Human domination of Earth’s ecosystems. Science 277, 494–499 (1997). 3. Kattenberg, A. et al. in Climate Change 1995. The Science of Climate Change(ed. Houghton, J. T.) 285–357 (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1996). insight review articles NATURE | VOL 405 | 11 MAY 2000 | www.nature.com 241 Change in biodiversity Cost to society Ecosystem functioning/ processes Time Time Time a b c 1 3 2 1 3b 3a 2 4 Figure 8 Ecosystem and societal consequences of changes in biodiversity. a, A linear change in biodiversity through time. b, This change might (1) induce a linear response in ecosystem processes, (2) have increasingly large impacts on ecosystem functioning, yielding exponential ecosystem change through time, or (3) exhibit abrupt thresholds owing to the loss of a keystone species, the loss of the last member of a key functional group, or the addition of a new species trait. c, Even if ecosystem response to diversity changes is linear, associated societal costs through time may respond nonlinearly. Departures from a linear increase (1) in societal costs over time might include larger cost increases (2) associated with each additional unit of change in ecosystem processes, yielding an exponential cost curve through time. Reductions of resource supply below threshold levels may induce step increases in societal costs (3a), such as reductions in water supply below the point where all consumers have access to enough for desired uses. If changes in resource supply or ecosystem processes exceed thresholds for supporting large segments of society, stepwise cost increases may be unmeasurable or essentially infinite (3b). The perceived ecological changes and societal costs of diversity change may be small (4). Actual, unrecognized costs may be far higher (lines 1, 2 and 3) and discovered only later as lost option values. Conservation of biodiversity can help avoid such negative ecological and economic ‘surprises’. © 2000 Macmillan Magazines Ltd