正在加载图片...

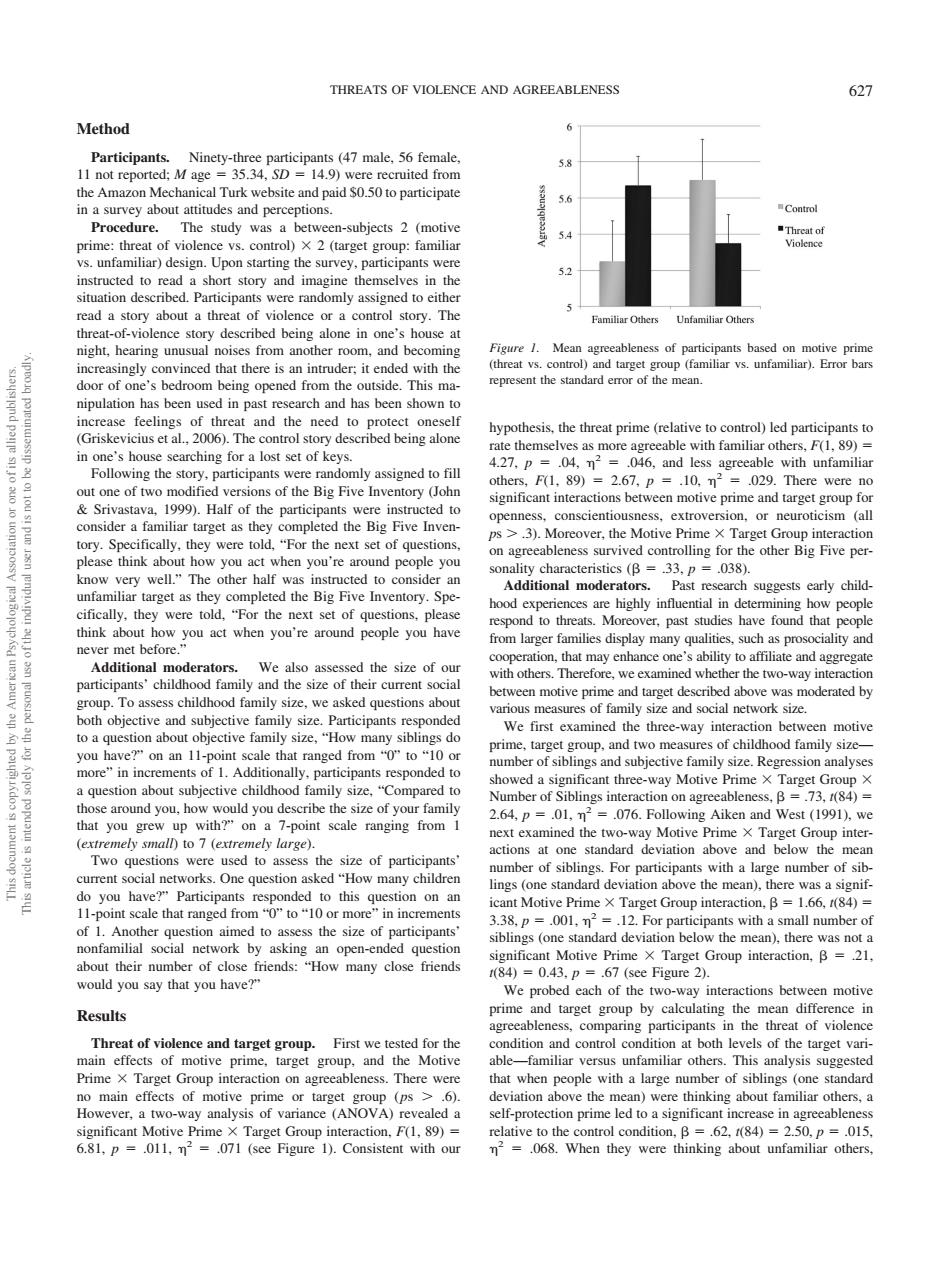

THREATS OF VIOLENCE AND AGREEABLENESS 627 Method 6 58 he Amazon Mec website and paid $0.50 to participate The stud subjects 2 (motiv (:familia shor The dro ease one mly assigned to fill 046.and less agreeable with unfamilia va.1999).Half of the nts were ins d to nscien arget mp eWGctrovciqn.orneuroticism(al leas think a you're ar und ple yor =.038 gcests earl child d the ally,they were told. the next set of questions. vou re pcople you have en motive prim noderated hy To ess childhood family size sked questions abou and target described abov ze and social nety s170 hav on an ll-poin cale that range "o"to of childhood family subjecti about subie Iyou.how would you des ibe the size of you you ranging from 016. and Two questions ere used to assess the of participa standard deviation abo oded to this o estion on an cale t anged fre 001.n Group interaction.B 6,84 n-ended que sibli (on ndard onfamilial social netw rk by as ).there waso iends many close end 80.43.p eGroup int We probed each of the two-way inter tions between motiv Results nditionand control c the were th ninking about f amiliar others, T p inte raction,F(1,89)= ive When they were thinking abou unfamiliar others Method Participants. Ninety-three participants (47 male, 56 female, 11 not reported; M age 35.34, SD 14.9) were recruited from the Amazon Mechanical Turk website and paid $0.50 to participate in a survey about attitudes and perceptions. Procedure. The study was a between-subjects 2 (motive prime: threat of violence vs. control) 2 (target group: familiar vs. unfamiliar) design. Upon starting the survey, participants were instructed to read a short story and imagine themselves in the situation described. Participants were randomly assigned to either read a story about a threat of violence or a control story. The threat-of-violence story described being alone in one’s house at night, hearing unusual noises from another room, and becoming increasingly convinced that there is an intruder; it ended with the door of one’s bedroom being opened from the outside. This manipulation has been used in past research and has been shown to increase feelings of threat and the need to protect oneself (Griskevicius et al., 2006). The control story described being alone in one’s house searching for a lost set of keys. Following the story, participants were randomly assigned to fill out one of two modified versions of the Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999). Half of the participants were instructed to consider a familiar target as they completed the Big Five Inventory. Specifically, they were told, “For the next set of questions, please think about how you act when you’re around people you know very well.” The other half was instructed to consider an unfamiliar target as they completed the Big Five Inventory. Specifically, they were told, “For the next set of questions, please think about how you act when you’re around people you have never met before.” Additional moderators. We also assessed the size of our participants’ childhood family and the size of their current social group. To assess childhood family size, we asked questions about both objective and subjective family size. Participants responded to a question about objective family size, “How many siblings do you have?” on an 11-point scale that ranged from “0” to “10 or more” in increments of 1. Additionally, participants responded to a question about subjective childhood family size, “Compared to those around you, how would you describe the size of your family that you grew up with?” on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely small) to 7 (extremely large). Two questions were used to assess the size of participants’ current social networks. One question asked “How many children do you have?” Participants responded to this question on an 11-point scale that ranged from “0” to “10 or more” in increments of 1. Another question aimed to assess the size of participants’ nonfamilial social network by asking an open-ended question about their number of close friends: “How many close friends would you say that you have?” Results Threat of violence and target group. First we tested for the main effects of motive prime, target group, and the Motive Prime Target Group interaction on agreeableness. There were no main effects of motive prime or target group (ps .6). However, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed a significant Motive Prime Target Group interaction, F(1, 89) 6.81, p .011, 2 .071 (see Figure 1). Consistent with our hypothesis, the threat prime (relative to control) led participants to rate themselves as more agreeable with familiar others, F(1, 89) 4.27, p .04, 2 .046, and less agreeable with unfamiliar others, F(1, 89) 2.67, p .10, 2 .029. There were no significant interactions between motive prime and target group for openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, or neuroticism (all ps .3). Moreover, the Motive Prime Target Group interaction on agreeableness survived controlling for the other Big Five personality characteristics ( .33, p .038). Additional moderators. Past research suggests early childhood experiences are highly influential in determining how people respond to threats. Moreover, past studies have found that people from larger families display many qualities, such as prosociality and cooperation, that may enhance one’s ability to affiliate and aggregate with others. Therefore, we examined whether the two-way interaction between motive prime and target described above was moderated by various measures of family size and social network size. We first examined the three-way interaction between motive prime, target group, and two measures of childhood family size— number of siblings and subjective family size. Regression analyses showed a significant three-way Motive Prime Target Group Number of Siblings interaction on agreeableness, .73, t(84) 2.64, p .01, 2 .076. Following Aiken and West (1991), we next examined the two-way Motive Prime Target Group interactions at one standard deviation above and below the mean number of siblings. For participants with a large number of siblings (one standard deviation above the mean), there was a significant Motive Prime Target Group interaction, 1.66, t(84) 3.38, p .001, 2 .12. For participants with a small number of siblings (one standard deviation below the mean), there was not a significant Motive Prime Target Group interaction, .21, t(84) 0.43, p .67 (see Figure 2). We probed each of the two-way interactions between motive prime and target group by calculating the mean difference in agreeableness, comparing participants in the threat of violence condition and control condition at both levels of the target variable—familiar versus unfamiliar others. This analysis suggested that when people with a large number of siblings (one standard deviation above the mean) were thinking about familiar others, a self-protection prime led to a significant increase in agreeableness relative to the control condition, .62, t(84) 2.50, p .015, 2 .068. When they were thinking about unfamiliar others, Figure 1. Mean agreeableness of participants based on motive prime (threat vs. control) and target group (familiar vs. unfamiliar). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. THREATS OF VIOLENCE AND AGREEABLENESS 627 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.�����