正在加载图片...

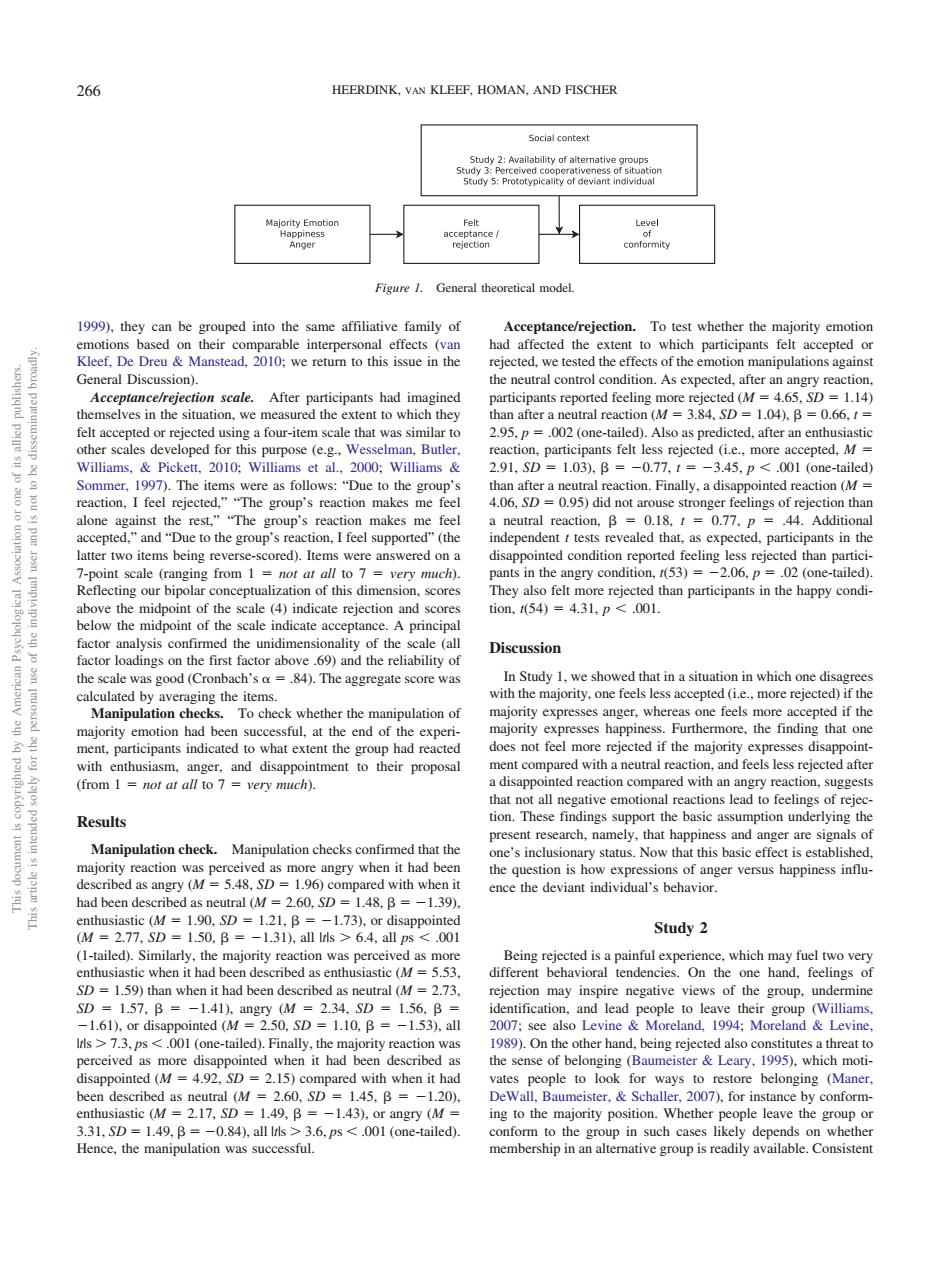

266 HEERDINK.VAN KLEEF.HOMAN.AND FISCHER soclalcontet 1999).they can be grouped into the same affiliative family of Acceptance/rejection.To test whether the maiority cmotion had the owhch participants e General discussion) the neutral control condition.As expected.after an angry reaction craecptedorrgjectcdusine ga four-item scale that was similar to 2000:Wili Sommer.197).The items were as follows:"Due to the group's "The makes me utral re andue to the groupseaction.I feel suppored(the -point scale (ranging ll pants in the angry condition.3)6.(onc-tailed) cate acceptan Discussion le was good (Cronbach's a=84).The aggregate score was ation in which wheter the manipulation of nger,wher cepted ifth the fi that on vith enthusiasm. ang s rejected after (from I =not at all to 7=very much). Results on. Manipulation check. a.Nowtht this basic effect s established. red with whenit 48 0.B Study 2 1.59)than when it had been de ribed as neutral (M 2.73 ejection may inspire negative views of the group,undermin 1610rd d00240B63 s.01(on-tailed)Finally.the disappointed (M=4.92.SD =2.15)con pared with when it had le to look for ways to restore belonging (Ma Wall,Baumeiste 2007,f y conform 31.sD=149.B= -0.84.al> 3.6.ps001 (one-tailed). membershipamative group is readily available form to the de Hence.the manipulation was successful 1999), they can be grouped into the same affiliative family of emotions based on their comparable interpersonal effects (van Kleef, De Dreu & Manstead, 2010; we return to this issue in the General Discussion). Acceptance/rejection scale. After participants had imagined themselves in the situation, we measured the extent to which they felt accepted or rejected using a four-item scale that was similar to other scales developed for this purpose (e.g., Wesselman, Butler, Williams, & Pickett, 2010; Williams et al., 2000; Williams & Sommer, 1997). The items were as follows: “Due to the group’s reaction, I feel rejected,” “The group’s reaction makes me feel alone against the rest,” “The group’s reaction makes me feel accepted,” and “Due to the group’s reaction, I feel supported” (the latter two items being reverse-scored). Items were answered on a 7-point scale (ranging from 1 not at all to 7 very much). Reflecting our bipolar conceptualization of this dimension, scores above the midpoint of the scale (4) indicate rejection and scores below the midpoint of the scale indicate acceptance. A principal factor analysis confirmed the unidimensionality of the scale (all factor loadings on the first factor above .69) and the reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s .84). The aggregate score was calculated by averaging the items. Manipulation checks. To check whether the manipulation of majority emotion had been successful, at the end of the experiment, participants indicated to what extent the group had reacted with enthusiasm, anger, and disappointment to their proposal (from 1 not at all to 7 very much). Results Manipulation check. Manipulation checks confirmed that the majority reaction was perceived as more angry when it had been described as angry (M 5.48, SD 1.96) compared with when it had been described as neutral (M 2.60, SD 1.48, 1.39), enthusiastic (M 1.90, SD 1.21, 1.73), or disappointed (M 2.77, SD 1.50, 1.31), all |t|s 6.4, all ps .001 (1-tailed). Similarly, the majority reaction was perceived as more enthusiastic when it had been described as enthusiastic (M 5.53, SD 1.59) than when it had been described as neutral (M 2.73, SD 1.57, 1.41), angry (M 2.34, SD 1.56, 1.61), or disappointed (M 2.50, SD 1.10, 1.53), all |t|s 7.3, ps .001 (one-tailed). Finally, the majority reaction was perceived as more disappointed when it had been described as disappointed (M 4.92, SD 2.15) compared with when it had been described as neutral (M 2.60, SD 1.45, 1.20), enthusiastic (M 2.17, SD 1.49, 1.43), or angry (M 3.31, SD 1.49, 0.84), all |t|s 3.6, ps .001 (one-tailed). Hence, the manipulation was successful. Acceptance/rejection. To test whether the majority emotion had affected the extent to which participants felt accepted or rejected, we tested the effects of the emotion manipulations against the neutral control condition. As expected, after an angry reaction, participants reported feeling more rejected (M 4.65, SD 1.14) than after a neutral reaction (M 3.84, SD 1.04), 0.66, t 2.95, p .002 (one-tailed). Also as predicted, after an enthusiastic reaction, participants felt less rejected (i.e., more accepted, M 2.91, SD 1.03), 0.77, t 3.45, p .001 (one-tailed) than after a neutral reaction. Finally, a disappointed reaction (M 4.06, SD 0.95) did not arouse stronger feelings of rejection than a neutral reaction, 0.18, t 0.77, p .44. Additional independent t tests revealed that, as expected, participants in the disappointed condition reported feeling less rejected than participants in the angry condition, t(53) 2.06, p .02 (one-tailed). They also felt more rejected than participants in the happy condition, t(54) 4.31, p .001. Discussion In Study 1, we showed that in a situation in which one disagrees with the majority, one feels less accepted (i.e., more rejected) if the majority expresses anger, whereas one feels more accepted if the majority expresses happiness. Furthermore, the finding that one does not feel more rejected if the majority expresses disappointment compared with a neutral reaction, and feels less rejected after a disappointed reaction compared with an angry reaction, suggests that not all negative emotional reactions lead to feelings of rejection. These findings support the basic assumption underlying the present research, namely, that happiness and anger are signals of one’s inclusionary status. Now that this basic effect is established, the question is how expressions of anger versus happiness influence the deviant individual’s behavior. Study 2 Being rejected is a painful experience, which may fuel two very different behavioral tendencies. On the one hand, feelings of rejection may inspire negative views of the group, undermine identification, and lead people to leave their group (Williams, 2007; see also Levine & Moreland, 1994; Moreland & Levine, 1989). On the other hand, being rejected also constitutes a threat to the sense of belonging (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), which motivates people to look for ways to restore belonging (Maner, DeWall, Baumeister, & Schaller, 2007), for instance by conforming to the majority position. Whether people leave the group or conform to the group in such cases likely depends on whether membership in an alternative group is readily available. Consistent Figure 1. General theoretical model. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 266 HEERDINK, VAN KLEEF, HOMAN, AND FISCHER�������������