正在加载图片...

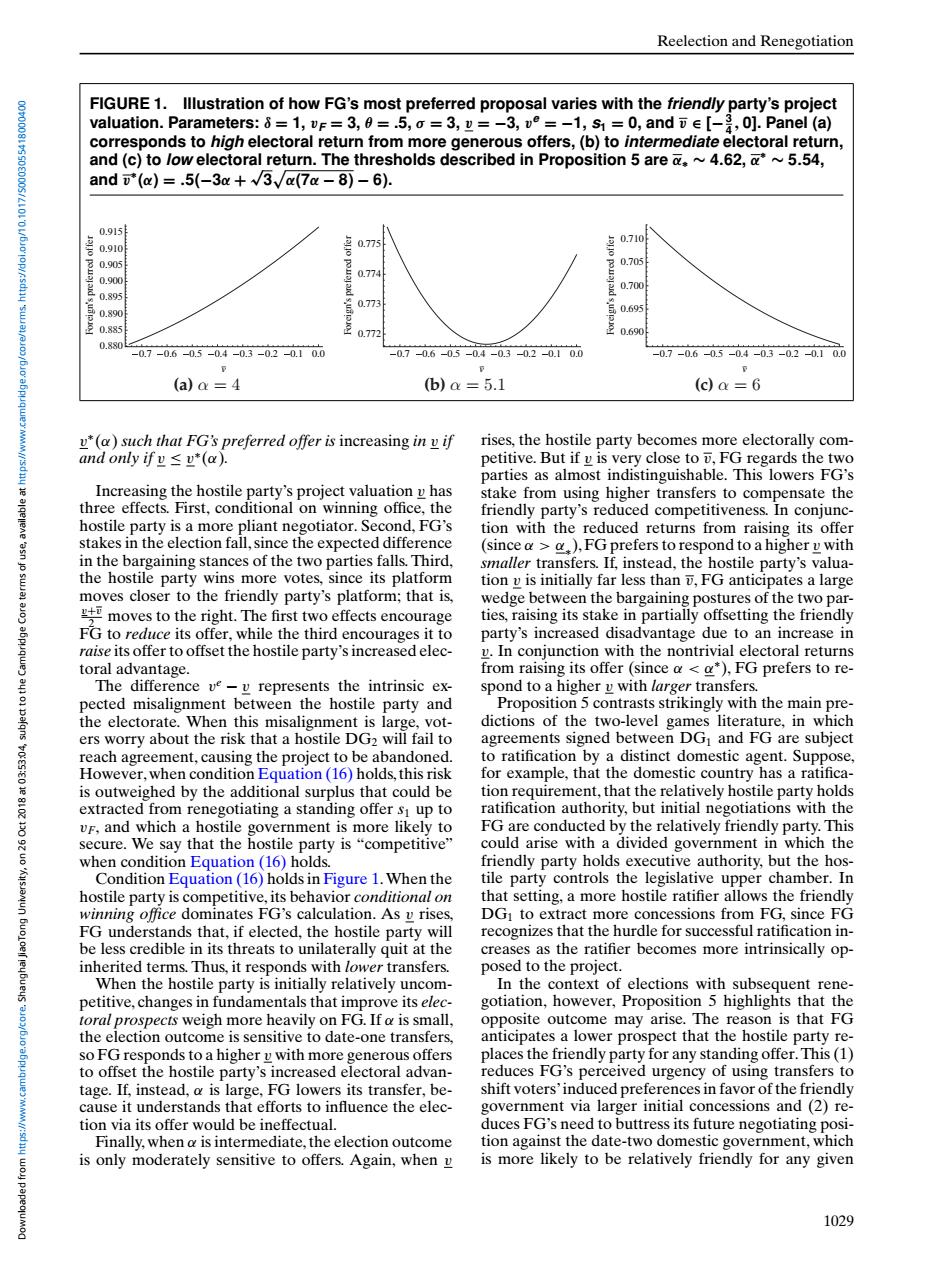

Reelection and Renegotiation FIGURE 1.Illustration of how FG's most preferred proposal varies with the friendly party's project valuation.Parameters:8=1,v=3,0=.5,o =3,v=-3,v=-1,s1=0,and [-0].Panel (a) corresponds to high electoral return from more generous offers,(b)to intermediate electoral return, and(c)to low electoral return.The thresholds described in Proposition 5 are .~4.62,~5.54, andv()=.5(-3a+√3√a(7a-8)-6). 0.915 0775 0.910 30.905 0.705 0.774 0.900 0.700 0.895 .77 0.890 0.885 20.772 0.690 0.880 -0.7-0.6-0.5-0.4-0.3-0.2-0.10.0 -0.7-0.6-05-0.4-0.3-0.2-0.10.0 -0.7-0.6-0.5-0.4-0.3-0.2-0.10.0 (a)a=4 (b)a=5.1 (c)a=6 v*(a)such that FG's preferred offer is increasing in v if rises,the hostile party becomes more electorally com- and only if v≤u*(a). petitive.But if v is very close to v,FG regards the two parties as almost indistinguishable.This lowers FG's Increasing the hostile party's project valuation v has stake from using higher transfers to compensate the 4号 three effects.First,conditional on winning office,the friendly party's reduced competitiveness.In conjunc- hostile party is a more pliant negotiator.Second,FG's tion with the reduced returns from raising its offer 'asn stakes in the election fall,since the expected difference (since a>a),FG prefers to respond to a higher v with in the bargaining stances of the two parties falls.Third, smaller transfers.If,instead,the hostile party's valua- the hostile party wins more votes,since its platform tion v is initially far less than FG anticipates a large moves closer to the friendly party's platform;that is, wedge between the bargaining postures of the two par- moves to the right.The first two effects encourage ties,raising its stake in partially offsetting the friendly FG to reduce its offer,while the third encourages it to party's increased disadvantage due to an increase in raise its offer to offset the hostile party's increased elec- v.In conjunction with the nontrivial electoral returns toral advantage. from raising its offer(since a<*),FG prefers to re- The difference ve-v represents the intrinsic ex- spond to a higher v with larger transfers. pected misalignment between the hostile party and Proposition 5 contrasts strikingly with the main pre- the electorate.When this misalignment is large,vot- dictions of the two-level games literature,in which ers worry about the risk that a hostile DG2 will fail to agreements signed between DG and FG are subject reach agreement,causing the project to be abandoned. to ratification by a distinct domestic agent.Suppose, However,when condition Equation (16)holds,this risk for example,that the domestic country has a ratifica- is outweighed by the additional surplus that could be tion requirement,that the relatively hostile party holds extracted from renegotiating a standing offer s up to ratification authority,but initial negotiations with the vF,and which a hostile government is more likely to FG are conducted by the relatively friendly party.This secure.We say that the hostile party is "competitive" could arise with a divided government in which the when condition Equation (16)holds. friendly party holds executive authority,but the hos- Condition Equation(16)holds in Figure 1.When the tile party controls the legislative upper chamber.In hostile party is competitive,its behavior conditional on that setting,a more hostile ratifier allows the friendly winning office dominates FG's calculation.As v rises, DGI to extract more concessions from FG.since FG FG understands that,if elected,the hostile party will recognizes that the hurdle for successful ratification in- be less credible in its threats to unilaterally quit at the creases as the ratifier becomes more intrinsically op- inherited terms.Thus,it responds with lower transfers. posed to the project. When the hostile party is initially relatively uncom In the context of elections with subsequent rene- petitive,changes in fundamentals that improve its elec- gotiation,however,Proposition 5 highlights that the toral prospects weigh more heavily on FG.If a is small, opposite outcome may arise.The reason is that FG the election outcome is sensitive to date-one transfers, anticipates a lower prospect that the hostile party re- so FG responds to a higher v with more generous offers places the friendly party for any standing offer.This(1) to offset the hostile party's increased electoral advan- reduces FG's perceived urgency of using transfers to tage.If,instead,a is large,FG lowers its transfer,be- shift voters'induced preferences in favor of the friendly cause it understands that efforts to influence the elec- government via larger initial concessions and (2)re- tion via its offer would be ineffectual. duces FG's need to buttress its future negotiating posi- Finally.when a is intermediate,the election outcome tion against the date-two domestic government,which is only moderately sensitive to offers.Again,when v is more likely to be relatively friendly for any given 1029Reelection and Renegotiation FIGURE 1. Illustration of how FG’s most preferred proposal varies with the friendly party’s project valuation. Parameters: δ = 1, vF = 3, θ = .5, σ = 3, v = −3, ve = −1, s1 = 0, and v ∈ [−3 4 , 0]. Panel (a) corresponds to high electoral return from more generous offers, (b) to intermediate electoral return, and (c) to low electoral return. The thresholds described in Proposition 5 are α∗ ∼ 4.62, α∗ ∼ 5.54, and v∗(α) = .5(−3α + √ 3 α(7α − 8) − 6). 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.880 0.885 0.890 0.895 0.900 0.905 0.910 0.915 v Foreign's preferred offer (a) α = 4 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.772 0.773 0.774 0.775 v Foreign's preferred offer (b) α = 5.1 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.690 0.695 0.700 0.705 0.710 v Foreign's preferred offer (c) α = 6 v∗(α) such that FG’s preferred offer is increasing in v if and only if v ≤ v∗(α). Increasing the hostile party’s project valuation v has three effects. First, conditional on winning office, the hostile party is a more pliant negotiator. Second, FG’s stakes in the election fall, since the expected difference in the bargaining stances of the two parties falls. Third, the hostile party wins more votes, since its platform moves closer to the friendly party’s platform; that is, v+v 2 moves to the right. The first two effects encourage FG to reduce its offer, while the third encourages it to raise its offer to offset the hostile party’s increased electoral advantage. The difference ve − v represents the intrinsic expected misalignment between the hostile party and the electorate. When this misalignment is large, voters worry about the risk that a hostile DG2 will fail to reach agreement, causing the project to be abandoned. However, when condition Equation (16) holds, this risk is outweighed by the additional surplus that could be extracted from renegotiating a standing offer s1 up to vF, and which a hostile government is more likely to secure. We say that the hostile party is “competitive” when condition Equation (16) holds. Condition Equation (16) holds in Figure 1.When the hostile party is competitive, its behavior conditional on winning office dominates FG’s calculation. As v rises, FG understands that, if elected, the hostile party will be less credible in its threats to unilaterally quit at the inherited terms. Thus, it responds with lower transfers. When the hostile party is initially relatively uncompetitive, changes in fundamentals that improve its electoral prospects weigh more heavily on FG. If α is small, the election outcome is sensitive to date-one transfers, so FG responds to a higher v with more generous offers to offset the hostile party’s increased electoral advantage. If, instead, α is large, FG lowers its transfer, because it understands that efforts to influence the election via its offer would be ineffectual. Finally, when α is intermediate, the election outcome is only moderately sensitive to offers. Again, when v rises, the hostile party becomes more electorally competitive. But if v is very close to v, FG regards the two parties as almost indistinguishable. This lowers FG’s stake from using higher transfers to compensate the friendly party’s reduced competitiveness. In conjunction with the reduced returns from raising its offer (since α>α∗), FG prefers to respond to a higher v with smaller transfers. If, instead, the hostile party’s valuation v is initially far less than v, FG anticipates a large wedge between the bargaining postures of the two parties, raising its stake in partially offsetting the friendly party’s increased disadvantage due to an increase in v. In conjunction with the nontrivial electoral returns from raising its offer (since α<α∗), FG prefers to respond to a higher v with larger transfers. Proposition 5 contrasts strikingly with the main predictions of the two-level games literature, in which agreements signed between DG1 and FG are subject to ratification by a distinct domestic agent. Suppose, for example, that the domestic country has a ratification requirement, that the relatively hostile party holds ratification authority, but initial negotiations with the FG are conducted by the relatively friendly party. This could arise with a divided government in which the friendly party holds executive authority, but the hostile party controls the legislative upper chamber. In that setting, a more hostile ratifier allows the friendly DG1 to extract more concessions from FG, since FG recognizes that the hurdle for successful ratification increases as the ratifier becomes more intrinsically opposed to the project. In the context of elections with subsequent renegotiation, however, Proposition 5 highlights that the opposite outcome may arise. The reason is that FG anticipates a lower prospect that the hostile party replaces the friendly party for any standing offer. This (1) reduces FG’s perceived urgency of using transfers to shift voters’induced preferences in favor of the friendly government via larger initial concessions and (2) reduces FG’s need to buttress its future negotiating position against the date-two domestic government, which is more likely to be relatively friendly for any given 1029 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Shanghai JiaoTong University, on 26 Oct 2018 at 03:53:04, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000400�