正在加载图片...

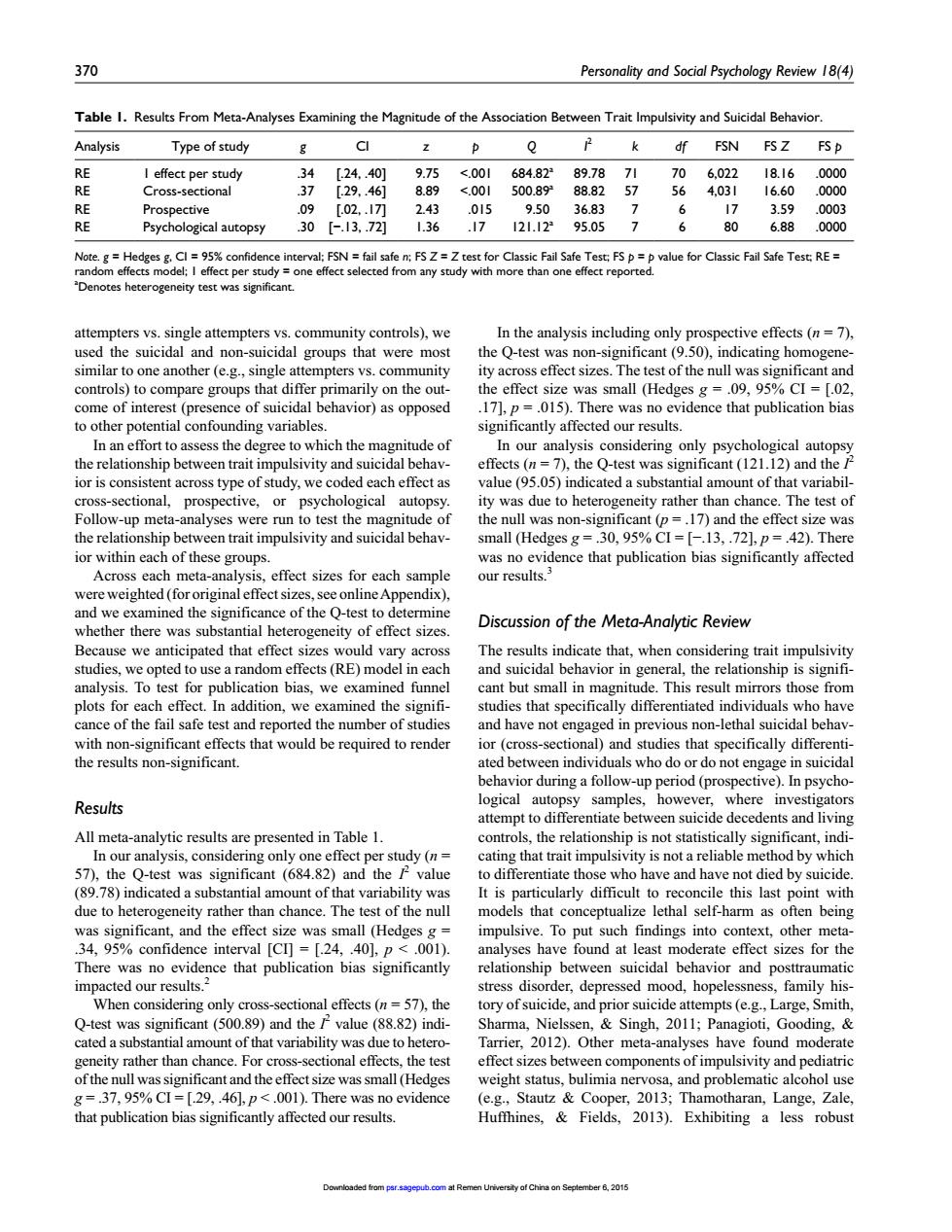

370 Personality and Social Psychology Review18( Table I.Results From Meta-Analyses Examining the Magnitude of the Association Between Trait Impulsivity and Suicidal Behavior. Analysis Type of study Q k df FSN FSZ FS p 4 24401 7 897871 706022 18160000 RE Cross-sectional 37 29.46 889 <001500.89 88.8257 56403 16.60 0000 RE Prospective [02..17] 243 30 3.59 ”sychological autopsy 30【-.13.72] .36 2 7 .0003 6.88 .0000 )we n the analysis in effects (n-7) groups were most Q-tes ating ty a controls)to compare groups that differ primarily on the out the effect size was small (Hedges9,95% come of inter of suicidal behavior)as opposed 17].p=015).There was no evidence that publication bias o othe effects(7)the O-test was signifieant (2112)and the ior is consistent across type of study,we coded each effect as value(95.05)indicated a substantial amount of that variabil s-sectional prospective or psychological autopsy tywas due to hete eity rathe tha The test of nd suicidal hehav mall(Hed as non-s 3000%Cm= 421T ior within each of these grouns was no evidence that publication bias significantly affected Across each meta-ar effect sizes fo each sampl our results were weighted( of the c whether there was substantial heterogeneity of effect sizes Discussion of the Meta-Analytic Review Because we anticipated that effect sizes would vary acros The results indicate that,when considering trait impulsivity studies to use a random ffects(RE)model in eac the relationship is signif To test pub cance of the fail safe test and reported the number of studies and have not engaged in previous non-lethal suicidal behav with non-significant effects that would be required to render the results non-significant etwee uals who d beha Results All meta-analytic results are presented in Table 1. contros,the relationship is not statistically significant,indi ing only 84.82 ect per study (n mpul od by whic It is particularly difficult to reconcile this last point with due to heterogeneity rather than chance.The test of the null models that conceptualize lethal self-harm as often being mall (Hedges g To put such findings into The cted our results. stress disorder,depressed mood,hopelessness,family his When consi ring only cross-sectional effects (n=57),the tory of suicide,and prior suicide attempts(e.g.,Large,Smith was signif cant (500 )and th value (88.82)ind m Singh,2011; Gooding, the te ect sizes h 8hcmassgicantandhceiectscwassma0Hetgs .bulimia nerv and g-37,95%C1 -[29,.46]p<001).There was no evidence e.g motharan,Lange,Zale that publication bias significantly affected our results Exhibiting a less robust 30 370 Personality and Social Psychology Review 18(4) attempters vs. single attempters vs. community controls), we used the suicidal and non-suicidal groups that were most similar to one another (e.g., single attempters vs. community controls) to compare groups that differ primarily on the outcome of interest (presence of suicidal behavior) as opposed to other potential confounding variables. In an effort to assess the degree to which the magnitude of the relationship between trait impulsivity and suicidal behavior is consistent across type of study, we coded each effect as cross-sectional, prospective, or psychological autopsy. Follow-up meta-analyses were run to test the magnitude of the relationship between trait impulsivity and suicidal behavior within each of these groups. Across each meta-analysis, effect sizes for each sample were weighted (for original effect sizes, see online Appendix), and we examined the significance of the Q-test to determine whether there was substantial heterogeneity of effect sizes. Because we anticipated that effect sizes would vary across studies, we opted to use a random effects (RE) model in each analysis. To test for publication bias, we examined funnel plots for each effect. In addition, we examined the significance of the fail safe test and reported the number of studies with non-significant effects that would be required to render the results non-significant. Results All meta-analytic results are presented in Table 1. In our analysis, considering only one effect per study (n = 57), the Q-test was significant (684.82) and the I 2 value (89.78) indicated a substantial amount of that variability was due to heterogeneity rather than chance. The test of the null was significant, and the effect size was small (Hedges g = .34, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [.24, .40], p < .001). There was no evidence that publication bias significantly impacted our results.2 When considering only cross-sectional effects (n = 57), the Q-test was significant (500.89) and the I 2 value (88.82) indicated a substantial amount of that variability was due to heterogeneity rather than chance. For cross-sectional effects, the test of the null was significant and the effect size was small (Hedges g = .37, 95% CI = [.29, .46], p < .001). There was no evidence that publication bias significantly affected our results. In the analysis including only prospective effects (n = 7), the Q-test was non-significant (9.50), indicating homogeneity across effect sizes. The test of the null was significant and the effect size was small (Hedges g = .09, 95% CI = [.02, .17], p = .015). There was no evidence that publication bias significantly affected our results. In our analysis considering only psychological autopsy effects (n = 7), the Q-test was significant (121.12) and the I 2 value (95.05) indicated a substantial amount of that variability was due to heterogeneity rather than chance. The test of the null was non-significant (p = .17) and the effect size was small (Hedges g = .30, 95% CI = [−.13, .72], p = .42). There was no evidence that publication bias significantly affected our results.3 Discussion of the Meta-Analytic Review The results indicate that, when considering trait impulsivity and suicidal behavior in general, the relationship is significant but small in magnitude. This result mirrors those from studies that specifically differentiated individuals who have and have not engaged in previous non-lethal suicidal behavior (cross-sectional) and studies that specifically differentiated between individuals who do or do not engage in suicidal behavior during a follow-up period (prospective). In psychological autopsy samples, however, where investigators attempt to differentiate between suicide decedents and living controls, the relationship is not statistically significant, indicating that trait impulsivity is not a reliable method by which to differentiate those who have and have not died by suicide. It is particularly difficult to reconcile this last point with models that conceptualize lethal self-harm as often being impulsive. To put such findings into context, other metaanalyses have found at least moderate effect sizes for the relationship between suicidal behavior and posttraumatic stress disorder, depressed mood, hopelessness, family history of suicide, and prior suicide attempts (e.g., Large, Smith, Sharma, Nielssen, & Singh, 2011; Panagioti, Gooding, & Tarrier, 2012). Other meta-analyses have found moderate effect sizes between components of impulsivity and pediatric weight status, bulimia nervosa, and problematic alcohol use (e.g., Stautz & Cooper, 2013; Thamotharan, Lange, Zale, Huffhines, & Fields, 2013). Exhibiting a less robust Table 1. Results From Meta-Analyses Examining the Magnitude of the Association Between Trait Impulsivity and Suicidal Behavior. Analysis Type of study g CI z p Q I2 k df FSN FS Z FS p RE 1 effect per study .34 [.24, .40] 9.75 <.001 684.82a 89.78 71 70 6,022 18.16 .0000 RE Cross-sectional .37 [.29, .46] 8.89 <.001 500.89a 88.82 57 56 4,031 16.60 .0000 RE Prospective .09 [.02, .17] 2.43 .015 9.50 36.83 7 6 17 3.59 .0003 RE Psychological autopsy .30 [−.13, .72] 1.36 .17 121.12a 95.05 7 6 80 6.88 .0000 Note. g = Hedges g, CI = 95% confidence interval; FSN = fail safe n; FS Z = Z test for Classic Fail Safe Test; FS p = p value for Classic Fail Safe Test; RE = random effects model; 1 effect per study = one effect selected from any study with more than one effect reported. a Denotes heterogeneity test was significant. Downloaded from psr.sagepub.com at Remen University of China on September 6, 2015