正在加载图片...

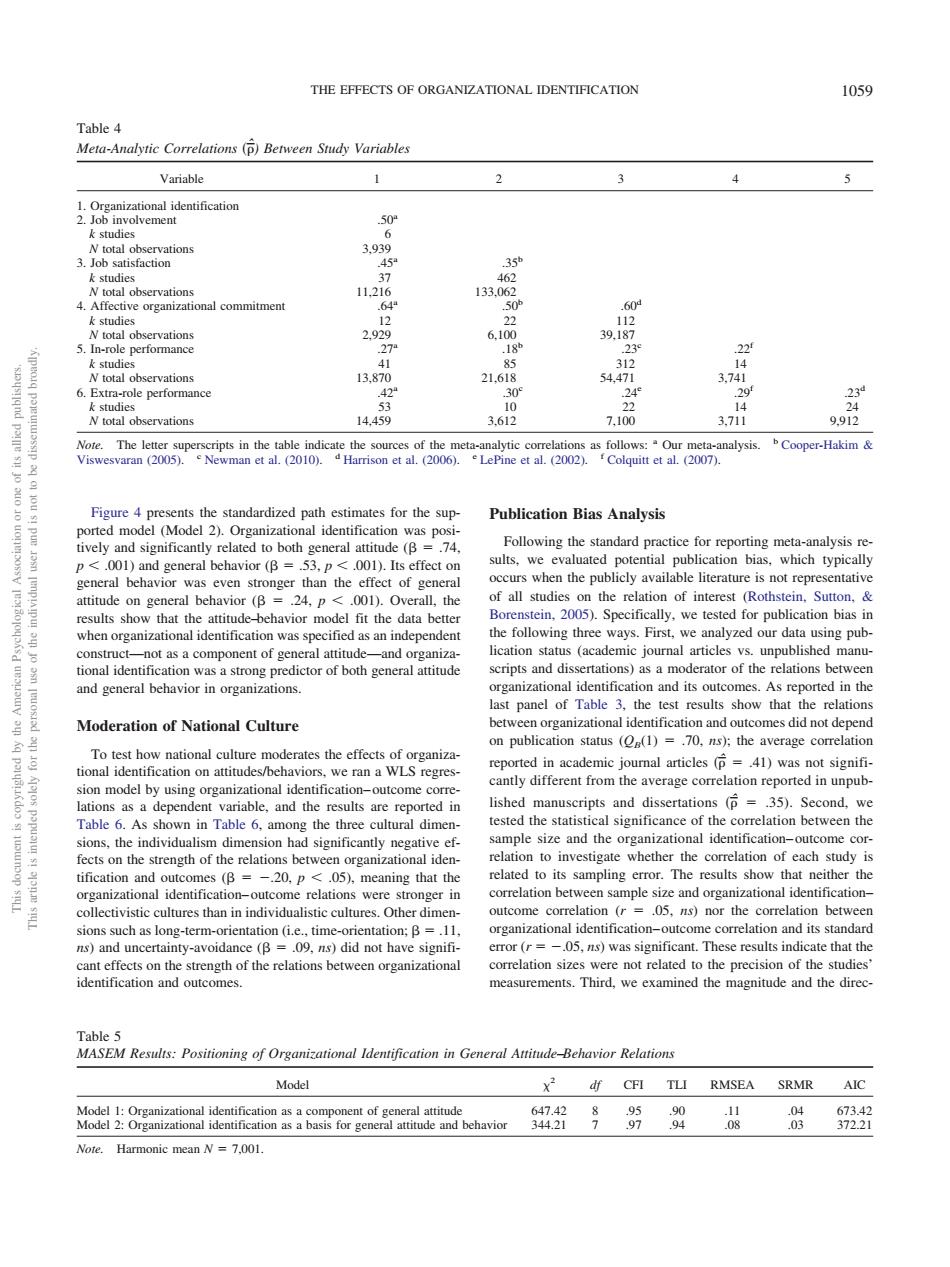

THE EFFECTS OF ORGANIZATIONAL IDENTIFICATION 1059 Table4 Meta-Analytic Correlations ()Between Study Variables Variable tion. 99与 nal commi me 3711 g912 Cooper-Hakim Publication Bias Analysis (B- Following the standard pr ult we valuated potential publication bias.which typically when the publicly available literature is not representati attitude on general behavior(B =24.p<001).Ove the following three ways.First,we analyzed our data using pub and general behavior in organizations. Moderation of National Culture on publication status (1)=70.ns):the average correlation ion reported in unpu ati s as a de variable,and the results are repor ed in 04 pe size and the organizational identificatior s on the strength of the relations bet th were relation between s nple size and organizati llectivistic cultures than in individualistic cultures.Othe ror (=-05,ms)was significant.These results indicate that the the precision of the studi latifictio in Cr i Model ydf CFI TLI RMSEA SRMR AIC Note.Harmonic mean N=7.001.Figure 4 presents the standardized path estimates for the supported model (Model 2). Organizational identification was positively and significantly related to both general attitude ( .74, p .001) and general behavior ( .53, p .001). Its effect on general behavior was even stronger than the effect of general attitude on general behavior ( .24, p .001). Overall, the results show that the attitude–behavior model fit the data better when organizational identification was specified as an independent construct—not as a component of general attitude—and organizational identification was a strong predictor of both general attitude and general behavior in organizations. Moderation of National Culture To test how national culture moderates the effects of organizational identification on attitudes/behaviors, we ran a WLS regression model by using organizational identification– outcome correlations as a dependent variable, and the results are reported in Table 6. As shown in Table 6, among the three cultural dimensions, the individualism dimension had significantly negative effects on the strength of the relations between organizational identification and outcomes (.20, p .05), meaning that the organizational identification– outcome relations were stronger in collectivistic cultures than in individualistic cultures. Other dimensions such as long-term-orientation (i.e., time-orientation; .11, ns) and uncertainty-avoidance ( .09, ns) did not have significant effects on the strength of the relations between organizational identification and outcomes. Publication Bias Analysis Following the standard practice for reporting meta-analysis results, we evaluated potential publication bias, which typically occurs when the publicly available literature is not representative of all studies on the relation of interest (Rothstein, Sutton, & Borenstein, 2005). Specifically, we tested for publication bias in the following three ways. First, we analyzed our data using publication status (academic journal articles vs. unpublished manuscripts and dissertations) as a moderator of the relations between organizational identification and its outcomes. As reported in the last panel of Table 3, the test results show that the relations between organizational identification and outcomes did not depend on publication status (QB(1) .70, ns); the average correlation reported in academic journal articles ˆ .41) was not significantly different from the average correlation reported in unpublished manuscripts and dissertations ˆ .35). Second, we tested the statistical significance of the correlation between the sample size and the organizational identification– outcome correlation to investigate whether the correlation of each study is related to its sampling error. The results show that neither the correlation between sample size and organizational identification– outcome correlation (r .05, ns) nor the correlation between organizational identification– outcome correlation and its standard error (r .05, ns) was significant. These results indicate that the correlation sizes were not related to the precision of the studies’ measurements. Third, we examined the magnitude and the direcTable 5 MASEM Results: Positioning of Organizational Identification in General Attitude–Behavior Relations Model 2 df CFI TLI RMSEA SRMR AIC Model 1: Organizational identification as a component of general attitude 647.42 8 .95 .90 .11 .04 673.42 Model 2: Organizational identification as a basis for general attitude and behavior 344.21 7 .97 .94 .08 .03 372.21 Note. Harmonic mean N 7,001. Table 4 Meta-Analytic Correlations ˆ) Between Study Variables Variable 1 2 3 4 5 1. Organizational identification 2. Job involvement .50a k studies 6 N total observations 3,939 3. Job satisfaction .45a .35b k studies 37 462 N total observations 11,216 133,062 4. Affective organizational commitment .64a .50b .60d k studies 12 22 112 N total observations 2,929 6,100 39,187 5. In-role performance .27a .18b .23c .22f k studies 41 85 312 14 N total observations 13,870 21,618 54,471 3,741 6. Extra-role performance .42a .30c .24e .29f .23d k studies 53 10 22 14 24 N total observations 14,459 3,612 7,100 3,711 9,912 Note. The letter superscripts in the table indicate the sources of the meta-analytic correlations as follows: a Our meta-analysis. b Cooper-Hakim & Viswesvaran (2005). c Newman et al. (2010). d Harrison et al. (2006). e LePine et al. (2002). f Colquitt et al. (2007). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. THE EFFECTS OF ORGANIZATIONAL IDENTIFICATION 1059���������������������