正在加载图片...

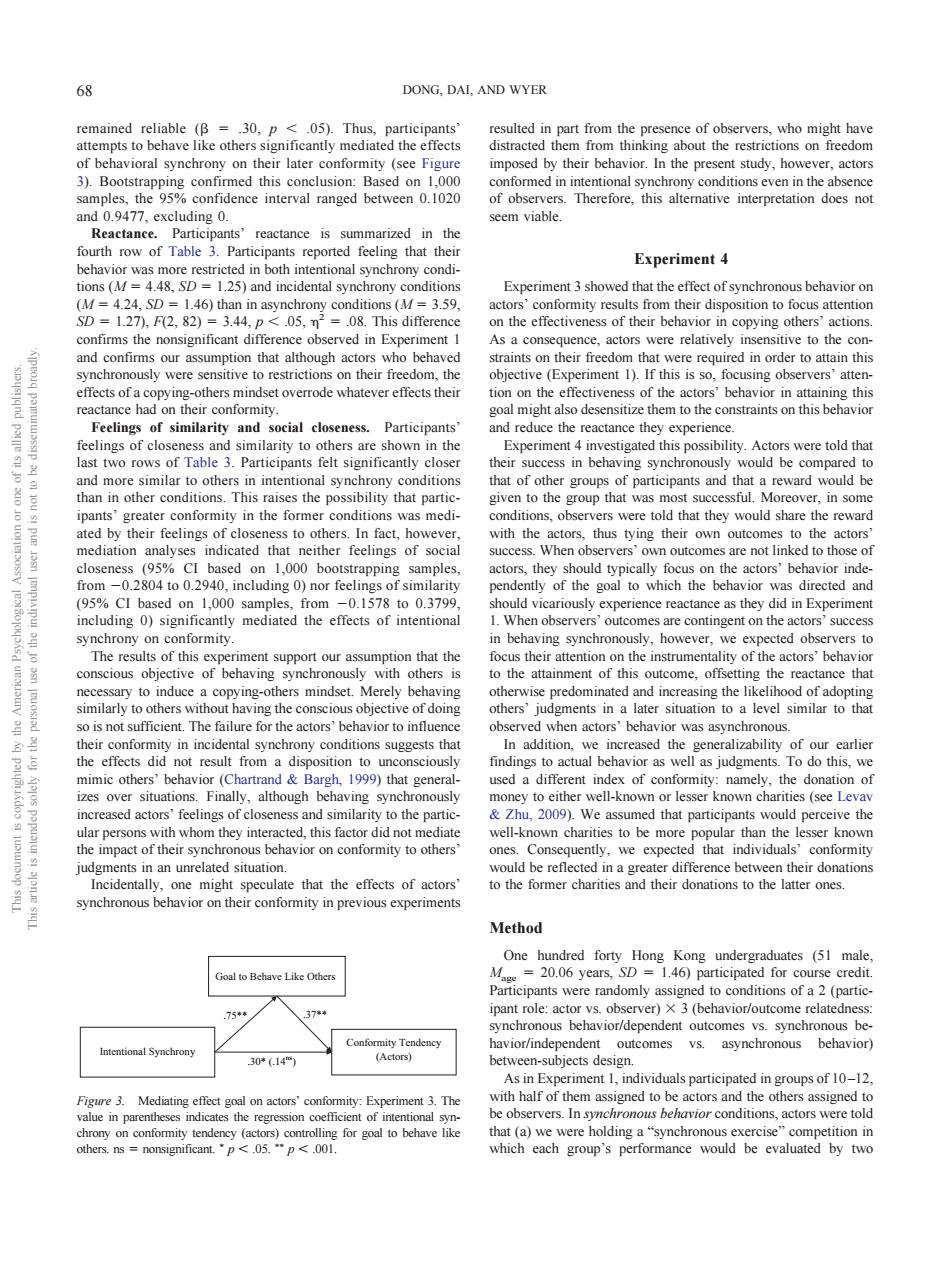

DONG,DAL.AND WYER )Boots ence cem viable d in both intentional synchrony Experiment 4 5)and inc dental s Experiment3 showed that the synchronous behavioro 424 ns the no s a co d nsve to objective (Exp ment )If this is so.focusing observersatte Feelings of similarity and social closeness. Participants and reduce the reactance they experience old tha ast two rows of Table 3.Participants felt significantly closer their dition reward ould b conditions was medi .000 bo ctor.they should thecors behavior ind 95%CI based on 1 000 samples from -01578t0379g nce reactance as they did in exr ncluding 0)significantly mediated the effects of intentiona cces The results of this ent supoo r a tion that the ality of the a rs'behay thers he a of this come.of s judgment To do this.w Finally although behaving d actor feelings of closene t of their behavior on conformity to others Cons we expected that conformit te that the effects of actors synchronous behavior n their in previous Method med to conditions of a 2 (partic chavior/outcom rclatcdncs outcomes vs.asynchronous behavior) ned t iticno which each group's performance would be evaluated by tworemained reliable ( .30, p .05). Thus, participants’ attempts to behave like others significantly mediated the effects of behavioral synchrony on their later conformity (see Figure 3). Bootstrapping confirmed this conclusion: Based on 1,000 samples, the 95% confidence interval ranged between 0.1020 and 0.9477, excluding 0. Reactance. Participants’ reactance is summarized in the fourth row of Table 3. Participants reported feeling that their behavior was more restricted in both intentional synchrony conditions (M 4.48, SD 1.25) and incidental synchrony conditions (M 4.24, SD 1.46) than in asynchrony conditions (M 3.59, SD 1.27), F(2, 82) 3.44, p .05, 2 .08. This difference confirms the nonsignificant difference observed in Experiment 1 and confirms our assumption that although actors who behaved synchronously were sensitive to restrictions on their freedom, the effects of a copying-others mindset overrode whatever effects their reactance had on their conformity. Feelings of similarity and social closeness. Participants’ feelings of closeness and similarity to others are shown in the last two rows of Table 3. Participants felt significantly closer and more similar to others in intentional synchrony conditions than in other conditions. This raises the possibility that participants’ greater conformity in the former conditions was mediated by their feelings of closeness to others. In fact, however, mediation analyses indicated that neither feelings of social closeness (95% CI based on 1,000 bootstrapping samples, from 0.2804 to 0.2940, including 0) nor feelings of similarity (95% CI based on 1,000 samples, from 0.1578 to 0.3799, including 0) significantly mediated the effects of intentional synchrony on conformity. The results of this experiment support our assumption that the conscious objective of behaving synchronously with others is necessary to induce a copying-others mindset. Merely behaving similarly to others without having the conscious objective of doing so is not sufficient. The failure for the actors’ behavior to influence their conformity in incidental synchrony conditions suggests that the effects did not result from a disposition to unconsciously mimic others’ behavior (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999) that generalizes over situations. Finally, although behaving synchronously increased actors’ feelings of closeness and similarity to the particular persons with whom they interacted, this factor did not mediate the impact of their synchronous behavior on conformity to others’ judgments in an unrelated situation. Incidentally, one might speculate that the effects of actors’ synchronous behavior on their conformity in previous experiments resulted in part from the presence of observers, who might have distracted them from thinking about the restrictions on freedom imposed by their behavior. In the present study, however, actors conformed in intentional synchrony conditions even in the absence of observers. Therefore, this alternative interpretation does not seem viable. Experiment 4 Experiment 3 showed that the effect of synchronous behavior on actors’ conformity results from their disposition to focus attention on the effectiveness of their behavior in copying others’ actions. As a consequence, actors were relatively insensitive to the constraints on their freedom that were required in order to attain this objective (Experiment 1). If this is so, focusing observers’ attention on the effectiveness of the actors’ behavior in attaining this goal might also desensitize them to the constraints on this behavior and reduce the reactance they experience. Experiment 4 investigated this possibility. Actors were told that their success in behaving synchronously would be compared to that of other groups of participants and that a reward would be given to the group that was most successful. Moreover, in some conditions, observers were told that they would share the reward with the actors, thus tying their own outcomes to the actors’ success. When observers’ own outcomes are not linked to those of actors, they should typically focus on the actors’ behavior independently of the goal to which the behavior was directed and should vicariously experience reactance as they did in Experiment 1. When observers’ outcomes are contingent on the actors’ success in behaving synchronously, however, we expected observers to focus their attention on the instrumentality of the actors’ behavior to the attainment of this outcome, offsetting the reactance that otherwise predominated and increasing the likelihood of adopting others’ judgments in a later situation to a level similar to that observed when actors’ behavior was asynchronous. In addition, we increased the generalizability of our earlier findings to actual behavior as well as judgments. To do this, we used a different index of conformity: namely, the donation of money to either well-known or lesser known charities (see Levav & Zhu, 2009). We assumed that participants would perceive the well-known charities to be more popular than the lesser known ones. Consequently, we expected that individuals’ conformity would be reflected in a greater difference between their donations to the former charities and their donations to the latter ones. Method One hundred forty Hong Kong undergraduates (51 male, Mage 20.06 years, SD 1.46) participated for course credit. Participants were randomly assigned to conditions of a 2 (participant role: actor vs. observer) 3 (behavior/outcome relatedness: synchronous behavior/dependent outcomes vs. synchronous behavior/independent outcomes vs. asynchronous behavior) between-subjects design. As in Experiment 1, individuals participated in groups of 10 –12, with half of them assigned to be actors and the others assigned to be observers. In synchronous behavior conditions, actors were told that (a) we were holding a “synchronous exercise” competition in which each group’s performance would be evaluated by two Intentional Synchrony Goal to Behave Like Others Conformity Tendency (Actors) .75** .37** .30* (.14ns) Figure 3. Mediating effect goal on actors’ conformity: Experiment 3. The value in parentheses indicates the regression coefficient of intentional synchrony on conformity tendency (actors) controlling for goal to behave like others. ns nonsignificant. p .05. p .001. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 68 DONG, DAI, AND WYER����������������