正在加载图片...

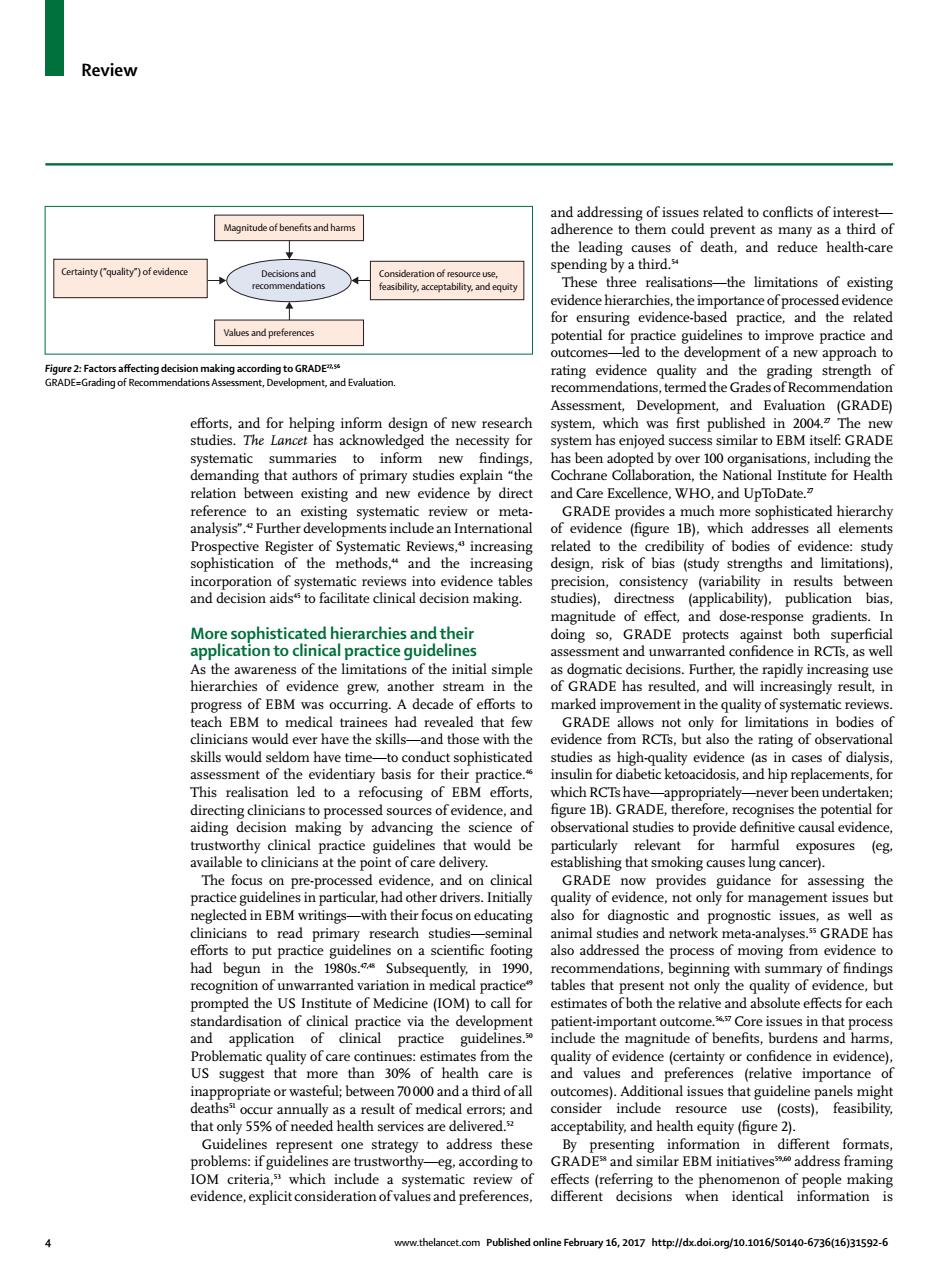

Review vent a s many as a third of ne hes three realisationsthe limitations of existing ringvie-based pracic he te ling strength IGRADE which was ummaries to inform has been adopted ttute for reference toan xising eview of Sys TndudeanlnteCreasin natic Re ed to th of bodies of eler stud and the increa sign. GRADE do grad ent rchies and their cal practice gui deline e and unwar in the ing.A cade ement in the d ever have the skills with the actice and hin s of diafo This realisa ation led to a refocusing of EBM eforts underta nal studies to pn sal evide or exposures (eg GRAD the and mina studi RADE ha had begun in the 1980s. Sub 0 1990 mendations begin with s of6nd recognit al pra that ly t tion of clinical portant outcome sues in that t from in evide that more than3 ofhea alue Add preferenc (rel dea onsider nclude use (costs).feasibility. alth services are ver ility,and th equity (figure nt for g.according to 16.2017htt∥fx doior10.1016/s0140-661631592.e Review 4 www.thelancet.com Published online February 16, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31592-6 eff orts, and for helping inform design of new research studies. The Lancet has acknowledged the necessity for systematic summaries to inform new fi ndings, demanding that authors of primary studies explain “the relation between existing and new evidence by direct reference to an existing systematic review or metaanalysis”.42 Further developments include an International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews,43 increasing sophistication of the methods,44 and the increasing incorporation of systematic reviews into evidence tables and decision aids45 to facilitate clinical decision making. More sophisticated hierarchies and their application to clinical practice guidelines As the awareness of the limitations of the initial simple hierarchies of evidence grew, another stream in the progress of EBM was occurring. A decade of eff orts to teach EBM to medical trainees had revealed that few clinicians would ever have the skills—and those with the skills would seldom have time—to conduct sophisticated assessment of the evidentiary basis for their practice.46 This realisation led to a refocusing of EBM eff orts, directing clinicians to processed sources of evidence, and aiding decision making by advancing the science of trustworthy clinical practice guidelines that would be available to clinicians at the point of care delivery. The focus on pre-processed evidence, and on clinical practice guidelines in particular, had other drivers. Initially neglected in EBM writings—with their focus on educating clinicians to read primary research studies—seminal eff orts to put practice guidelines on a scientifi c footing had begun in the 1980s.47,48 Subsequently, in 1990, recognition of unwarranted variation in medical practice49 prompted the US Institute of Medicine (IOM) to call for standardisation of clinical practice via the development and application of clinical practice guidelines.50 Problematic quality of care continues: estimates from the US suggest that more than 30% of health care is inappropriate or wasteful; between 70 000 and a third of all deaths51 occur annually as a result of medical errors; and that only 55% of needed health services are delivered.52 Guidelines represent one strategy to address these problems: if guidelines are trustworthy—eg, according to IOM criteria,53 which include a systematic review of evidence, explicit consideration of values and preferences, and addressing of issues related to confl icts of interest— adherence to them could prevent as many as a third of the leading causes of death, and reduce health-care spending by a third.54 These three realisations—the limitations of existing evidence hierarchies, the importance of processed evidence for ensuring evidence-based practice, and the related potential for practice guidelines to improve practice and outcomes—led to the development of a new approach to rating evidence quality and the grading strength of recommendations, termed the Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system, which was fi rst published in 2004.27 The new system has enjoyed success similar to EBM itself: GRADE has been adopted by over 100 organisations, including the Cochrane Collaboration, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, WHO, and UpToDate.27 GRADE provides a much more sophisticated hierarchy of evidence (fi gure 1B), which addresses all elements related to the credibility of bodies of evidence: study design, risk of bias (study strengths and limitations), precision, consistency (variability in results between studies), directness (applicability), publication bias, magnitude of eff ect, and dose-response gradients. In doing so, GRADE protects against both superfi cial assessment and unwarranted confi dence in RCTs, as well as dogmatic decisions. Further, the rapidly increasing use of GRADE has resulted, and will increasingly result, in marked improvement in the quality of systematic reviews. GRADE allows not only for limitations in bodies of evidence from RCTs, but also the rating of observational studies as high-quality evidence (as in cases of dialysis, insulin for diabetic ketoacidosis, and hip replacements, for which RCTs have—appropriately—never been undertaken; fi gure 1B). GRADE, therefore, recognises the potential for observational studies to provide defi nitive causal evidence, particularly relevant for harmful exposures (eg, establishing that smoking causes lung cancer). GRADE now provides guidance for assessing the quality of evidence, not only for management issues but also for diagnostic and prognostic issues, as well as animal studies and network meta-analyses.55 GRADE has also addressed the process of moving from evidence to recommendations, beginning with summary of fi ndings tables that present not only the quality of evidence, but estimates of both the relative and absolute eff ects for each patient-important outcome.56,57 Core issues in that process include the magnitude of benefi ts, burdens and harms, quality of evidence (certainty or confi dence in evidence), and values and preferences (relative importance of outcomes). Additional issues that guideline panels might consider include resource use (costs), feasibility, acceptability, and health equity (fi gure 2). By presenting information in diff erent formats, GRADE58 and similar EBM initiatives59,60 address framing eff ects (referring to the phenomenon of people making diff erent decisions when identical information is Magnitude of benefits and harms Values and preferences Certainty (”quality”) of evidence Consideration of resource use, feasibility, acceptability, and equity Decisions and recommendations Figure 2: Factors aff ecting decision making according to GRADE27, 56 GRADE=Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation