正在加载图片...

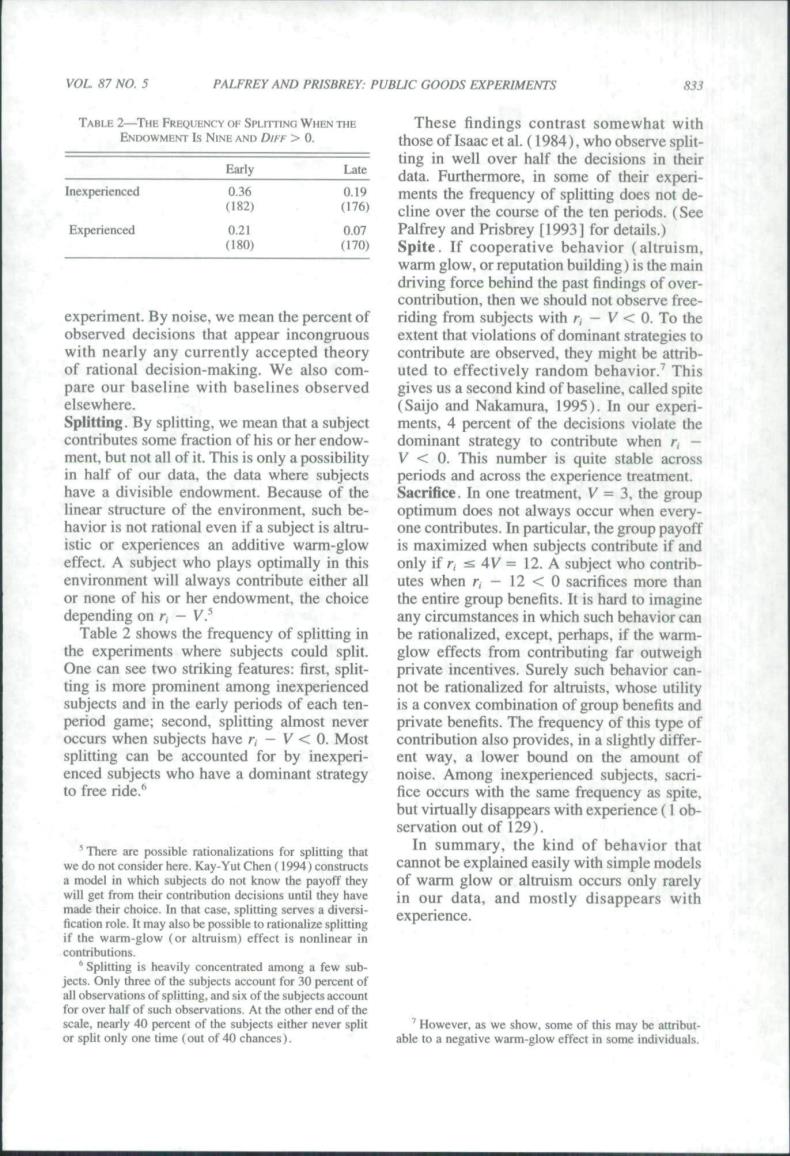

VOL 87 NO.5 PALFREY AND PRISBREY:PUBLIC GOODS EXPERIMENTS These findings Early Late ting in well over half the decisions in their 8 、har中e0ceyo9pga6soe ments the Experienced Palfrey and for details.) Spite.If cooperative behavior (altruism. nngs of over experiment.By noise,we mean the percent of riding from subjects with0.To the extent that violations of dominant strategies to pare our baseline with baselines observe elsewhere. Splitting.By splitting.we ean that a subject or her 起 strategy when r have a divisible endowment.Because of the Sacrifice.In one treatment,V=3.the group nent,such be. istic or exeri ces ane effect.A subject who plays optimally in this only=12.A subject who contrib oonendowment.the choice utes when r 12 <0 sacrifices more than or her endowment,the choice It is hard to imagine y of splitting in if the the experiments where subjects could split One Surely such behavior can t among vate benefits.The eof this occurs V<0.Mos contribution also provides. splitting can be ent way,a lower bound on the amount ol subjects,sa but virtually disap ears with experience( servation out of 129). thekind of behavior that sily with simpl in our data,and mostly disappears with experience. half of such obe VOL 87 NO. 5 PALFREY AND PRISBREY: PUBUC GOODS EXPERIMENTS 833 TABLE 2—THE FREQUENCY OF SPLITTING WHEN THE ENDOWMENT IS NINE AND DIFF > 0. Early Late fnexperienced Experienced 0.36 (182) 0.21 (180) 0.19 (176) 0.07 (170) experiment. By noise, we mean the percent of observed decisions that appear incongruous with nearly any currently accepted theory of rational decision-making. We also compare our baseline with baselines observed elsewhere. Splitting. By splitting, we mean that a subject contributes some fraction of his or her endowment, but not all of it. This is only a possibility in half of our data, the data where subjects have a divisible endowment. Because of the linear structure of the environment, such behavior is not rational even if a subject is altruistic or experiences an additive warm-glow effect. A subject who plays optimally in this environment will always contribute either all or none of his or her endowment, the choice depending on r^ - V.^ Table 2 shows the frequency of splitting in the experiments where subjects could split. One can see two striking features: first, splitting is more prominent among inexperienced suhjects and in the early periods of each tenperiod game; second, splitting almost never occurs when subjects have r, — V < 0. Most splitting can be accounted for by inexperienced subjects who have a dominant strategy to free ride.*" ^' There are possible rationalizations for splitting that we do not consider here. Kay-Yut Chen (1994) constructs a model in which suhjects do not know the payoff they will get from their contribution decisions until they have made their choice. In ihat case, splitting serves a diversification role. It may also be possihle to rationalize splitting if the warm-glow (or altruism) effect is nonlinear in contributions. '' Splitting is heavily concentrated among a few subjects. Only three of the subjects account for 30 percent of all observations of splitting, and six of the subjects account for over half of such observations. At the other end of the scale, nearly 40 percent of the subjects either never split or split only one time (out of 40 chances). These findings contrast somewhat with those of Isaac et al. (1984), who observe splitting in well over half the decisions in their data. Furthermore, in some of their experiments the frequency of splitting does not decline over the course of the ten periods. (See Palfrey and Prisbrey 11993] for details.) Spite. If cooperative behavior (altruism, warm glow, or reputation building) is the main driving force behind the past findings of overcontribution, then we should not observe freeriding from subjects with r, - V < 0. To the extent that violations of dominant strategies to contribute are observed, they might be attributed to effectively random behavior.' This gives us a second kind of baseline, called spite (Saijo and Nakamura, 1995). In our experiments, 4 percent of the decisions violate the dominant strategy to contribute when r^ — V < 0. This number is quite stable across periods and across the experience treatment. Sacrifice. In one treatment, V = 3, the group optimum does not always occur when everyone contributes. In particular, the group payoff is maximized when subjects contribute if and only if r, < 4V = 12. A subject who contributes when r, - 12 < 0 sacrifices more than the entire group benefits. It is hard to imagine any circumstances in which such behavior can be rationalized, except, perhaps, if the warmglow effects from contributing far outweigh private incentives. Surely such behavior cannot be rationalized for altruists, whose utility is a convex combination of group benefits and private benefits. The frequency of this type of contribution also provides, in a slightly different way, a lower bound on the amount of noise. Among inexperienced subjects, sacrifice occurs with the same frequency as spite, but virtually disappears with experience (1 observation out of 129). In summary, the kind of behavior that cannot be explained easily with simple models of warm glow or altruism occurs only rarely in our data, and mostly disappears with experience. ' However, as we show, some of this may be attributable to a negative warm-glow effect in some individuals