正在加载图片...

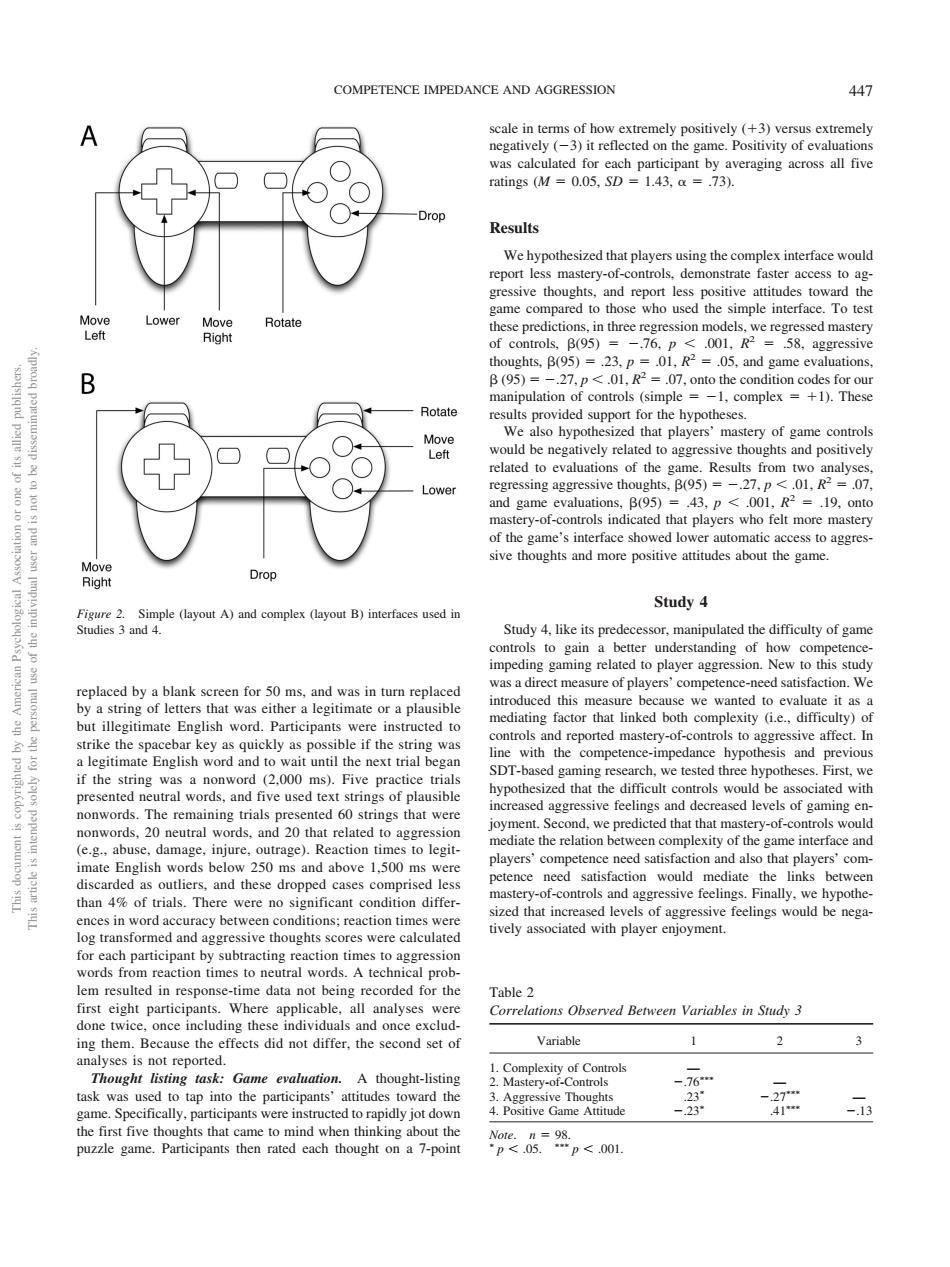

COMPETENCE IMPEDANCE AND AGGRESSION 447 ed on the s all five Results We hypothesized that players using the complex interface would Rotate +】 vould be negatively related to aggressive thoughts and positively of the game's interface showed lower e thoughts and more positive attitudes about the game. e ()d pe (ay Study4 mpeding ga aced by a blank s en for 50 ms and was in tur n roduced this masu ire bayers' we wanted to evaluate it as glish word.F iating factor that linked both complexity()o legitimate English word and to wait until the next trial be ine SDT-be that the ch,we tes three hypothes e.g. abuse,damage,injure,outrage)Reaction times to legit players'competence need satisfaction and also that players'com nd the ms and above 1500ma1es 4%of trials.There were no si ficant or ach participant by subtracting em resulted in resno ime data not being orded for the participants Variable 2 oward the 4.Positive Came Auitud puzzle game.Participants then rated each thought on a 7-point s8,<0Lreplaced by a blank screen for 50 ms, and was in turn replaced by a string of letters that was either a legitimate or a plausible but illegitimate English word. Participants were instructed to strike the spacebar key as quickly as possible if the string was a legitimate English word and to wait until the next trial began if the string was a nonword (2,000 ms). Five practice trials presented neutral words, and five used text strings of plausible nonwords. The remaining trials presented 60 strings that were nonwords, 20 neutral words, and 20 that related to aggression (e.g., abuse, damage, injure, outrage). Reaction times to legitimate English words below 250 ms and above 1,500 ms were discarded as outliers, and these dropped cases comprised less than 4% of trials. There were no significant condition differences in word accuracy between conditions; reaction times were log transformed and aggressive thoughts scores were calculated for each participant by subtracting reaction times to aggression words from reaction times to neutral words. A technical problem resulted in response-time data not being recorded for the first eight participants. Where applicable, all analyses were done twice, once including these individuals and once excluding them. Because the effects did not differ, the second set of analyses is not reported. Thought listing task: Game evaluation. A thought-listing task was used to tap into the participants’ attitudes toward the game. Specifically, participants were instructed to rapidly jot down the first five thoughts that came to mind when thinking about the puzzle game. Participants then rated each thought on a 7-point scale in terms of how extremely positively (3) versus extremely negatively (3) it reflected on the game. Positivity of evaluations was calculated for each participant by averaging across all five ratings (M 0.05, SD 1.43, .73). Results We hypothesized that players using the complex interface would report less mastery-of-controls, demonstrate faster access to aggressive thoughts, and report less positive attitudes toward the game compared to those who used the simple interface. To test these predictions, in three regression models, we regressed mastery of controls, (95) .76, p .001, R2 .58, aggressive thoughts, (95) .23, p .01, R2 .05, and game evaluations, (95) .27, p .01, R2 .07, onto the condition codes for our manipulation of controls (simple 1, complex 1). These results provided support for the hypotheses. We also hypothesized that players’ mastery of game controls would be negatively related to aggressive thoughts and positively related to evaluations of the game. Results from two analyses, regressing aggressive thoughts, (95) .27, p .01, R2 .07, and game evaluations, (95) .43, p .001, R2 .19, onto mastery-of-controls indicated that players who felt more mastery of the game’s interface showed lower automatic access to aggressive thoughts and more positive attitudes about the game. Study 4 Study 4, like its predecessor, manipulated the difficulty of game controls to gain a better understanding of how competenceimpeding gaming related to player aggression. New to this study was a direct measure of players’ competence-need satisfaction. We introduced this measure because we wanted to evaluate it as a mediating factor that linked both complexity (i.e., difficulty) of controls and reported mastery-of-controls to aggressive affect. In line with the competence-impedance hypothesis and previous SDT-based gaming research, we tested three hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that the difficult controls would be associated with increased aggressive feelings and decreased levels of gaming enjoyment. Second, we predicted that that mastery-of-controls would mediate the relation between complexity of the game interface and players’ competence need satisfaction and also that players’ competence need satisfaction would mediate the links between mastery-of-controls and aggressive feelings. Finally, we hypothesized that increased levels of aggressive feelings would be negatively associated with player enjoyment. Table 2 Correlations Observed Between Variables in Study 3 Variable 1 2 3 1. Complexity of Controls — 2. Mastery-of-Controls .76 — 3. Aggressive Thoughts .23 .27 — 4. Positive Game Attitude .23 .41 .13 Note. n 98. p .05. p .001. Figure 2. Simple (layout A) and complex (layout B) interfaces used in Studies 3 and 4. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. COMPETENCE IMPEDANCE AND AGGRESSION 447�������