正在加载图片...

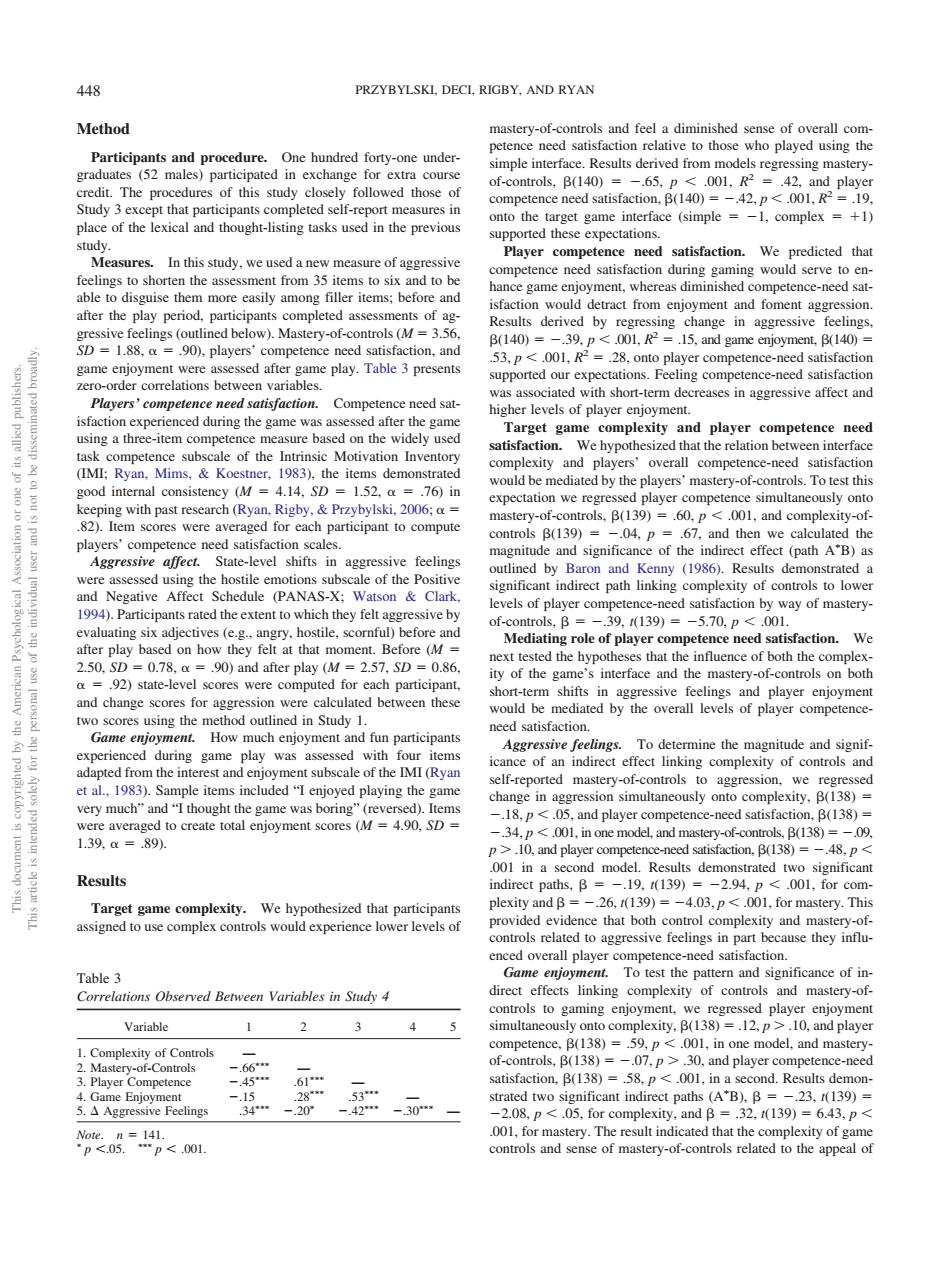

448 PRZYBYLSKI.DECI.RIGBY.AND RYAN Method sing ma onto the Supported these expectationsce (simple complex We redicted that Measures.In this studv.we used a n measure of ag ings to shorten the assessment from 35 i compet after the play period. sfaction would detract from enj nent and foment aggre nge in aggressive ed satisfaction gnmeee Comp of the Int M:Ryan.Mims.Ko overall competer e-need satisfactio sed player simultaneously ont na 60.P< tem scores were averaged for ea h participant to compute 001.and omplexity-of Aggressire afect.Suate-level shifs in nitu of the effect (path A"B) 1986 nd Clark 0 faction by way of mastery. ssive b evels of player cor 139 50 -0.78.90)and after play (M 257.5D=0.86 nd change scores for ago ssion were calculated between these hon-t nced during game was as ive feelings. nc i nt su of the tal.1983). 139.=89 tisfaction,B(138) 48.p Results ndirect paths.B= 19139=d -2.94.D 001.for com We h hesized that participant h39 .fo d play To test the paue m and significance of in- ions Observed Betwveen Variables in Sudy4 t effects linking complexity of control and mastery-of Variable 1 3 45 and mastery satisfaction,B(138)=.ina second.Results demon- -30二 001,form Method Participants and procedure. One hundred forty-one undergraduates (52 males) participated in exchange for extra course credit. The procedures of this study closely followed those of Study 3 except that participants completed self-report measures in place of the lexical and thought-listing tasks used in the previous study. Measures. In this study, we used a new measure of aggressive feelings to shorten the assessment from 35 items to six and to be able to disguise them more easily among filler items; before and after the play period, participants completed assessments of aggressive feelings (outlined below). Mastery-of-controls (M 3.56, SD 1.88, .90), players’ competence need satisfaction, and game enjoyment were assessed after game play. Table 3 presents zero-order correlations between variables. Players’ competence need satisfaction. Competence need satisfaction experienced during the game was assessed after the game using a three-item competence measure based on the widely used task competence subscale of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI; Ryan, Mims, & Koestner, 1983), the items demonstrated good internal consistency (M 4.14, SD 1.52, .76) in keeping with past research (Ryan, Rigby, & Przybylski, 2006; .82). Item scores were averaged for each participant to compute players’ competence need satisfaction scales. Aggressive affect. State-level shifts in aggressive feelings were assessed using the hostile emotions subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1994). Participants rated the extent to which they felt aggressive by evaluating six adjectives (e.g., angry, hostile, scornful) before and after play based on how they felt at that moment. Before (M 2.50, SD 0.78, .90) and after play (M 2.57, SD 0.86, .92) state-level scores were computed for each participant, and change scores for aggression were calculated between these two scores using the method outlined in Study 1. Game enjoyment. How much enjoyment and fun participants experienced during game play was assessed with four items adapted from the interest and enjoyment subscale of the IMI (Ryan et al., 1983). Sample items included “I enjoyed playing the game very much” and “I thought the game was boring” (reversed). Items were averaged to create total enjoyment scores (M 4.90, SD 1.39, .89). Results Target game complexity. We hypothesized that participants assigned to use complex controls would experience lower levels of mastery-of-controls and feel a diminished sense of overall competence need satisfaction relative to those who played using the simple interface. Results derived from models regressing masteryof-controls, (140) .65, p .001, R2 .42, and player competence need satisfaction, (140) .42, p .001, R2 .19, onto the target game interface (simple 1, complex 1) supported these expectations. Player competence need satisfaction. We predicted that competence need satisfaction during gaming would serve to enhance game enjoyment, whereas diminished competence-need satisfaction would detract from enjoyment and foment aggression. Results derived by regressing change in aggressive feelings, (140) .39, p .001, R2 .15, and game enjoyment, (140) .53, p .001, R2 .28, onto player competence-need satisfaction supported our expectations. Feeling competence-need satisfaction was associated with short-term decreases in aggressive affect and higher levels of player enjoyment. Target game complexity and player competence need satisfaction. We hypothesized that the relation between interface complexity and players’ overall competence-need satisfaction would be mediated by the players’ mastery-of-controls. To test this expectation we regressed player competence simultaneously onto mastery-of-controls, (139) .60, p .001, and complexity-ofcontrols (139) .04, p .67, and then we calculated the magnitude and significance of the indirect effect (path A B) as outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986). Results demonstrated a significant indirect path linking complexity of controls to lower levels of player competence-need satisfaction by way of masteryof-controls, .39, t(139) 5.70, p .001. Mediating role of player competence need satisfaction. We next tested the hypotheses that the influence of both the complexity of the game’s interface and the mastery-of-controls on both short-term shifts in aggressive feelings and player enjoyment would be mediated by the overall levels of player competenceneed satisfaction. Aggressive feelings. To determine the magnitude and significance of an indirect effect linking complexity of controls and self-reported mastery-of-controls to aggression, we regressed change in aggression simultaneously onto complexity, (138) .18, p .05, and player competence-need satisfaction, (138) .34, p .001, in one model, and mastery-of-controls, (138) .09, p .10, and player competence-need satisfaction, (138) .48, p .001 in a second model. Results demonstrated two significant indirect paths, .19, t(139) 2.94, p .001, for complexity and .26, t(139) 4.03, p .001, for mastery. This provided evidence that both control complexity and mastery-ofcontrols related to aggressive feelings in part because they influenced overall player competence-need satisfaction. Game enjoyment. To test the pattern and significance of indirect effects linking complexity of controls and mastery-ofcontrols to gaming enjoyment, we regressed player enjoyment simultaneously onto complexity, (138) .12, p .10, and player competence, (138) .59, p .001, in one model, and masteryof-controls, (138) .07, p .30, and player competence-need satisfaction, (138) .58, p .001, in a second. Results demonstrated two significant indirect paths (A B), .23, t(139) 2.08, p .05, for complexity, and .32, t(139) 6.43, p .001, for mastery. The result indicated that the complexity of game controls and sense of mastery-of-controls related to the appeal of Table 3 Correlations Observed Between Variables in Study 4 Variable 1 2 3 4 5 1. Complexity of Controls — 2. Mastery-of-Controls .66 — 3. Player Competence .45 .61 — 4. Game Enjoyment .15 .28 .53 — 5. Aggressive Feelings .34 .20 .42 .30 — Note. n 141. p .05. p .001. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 448 PRZYBYLSKI, DECI, RIGBY, AND RYAN�����������������������