正在加载图片...

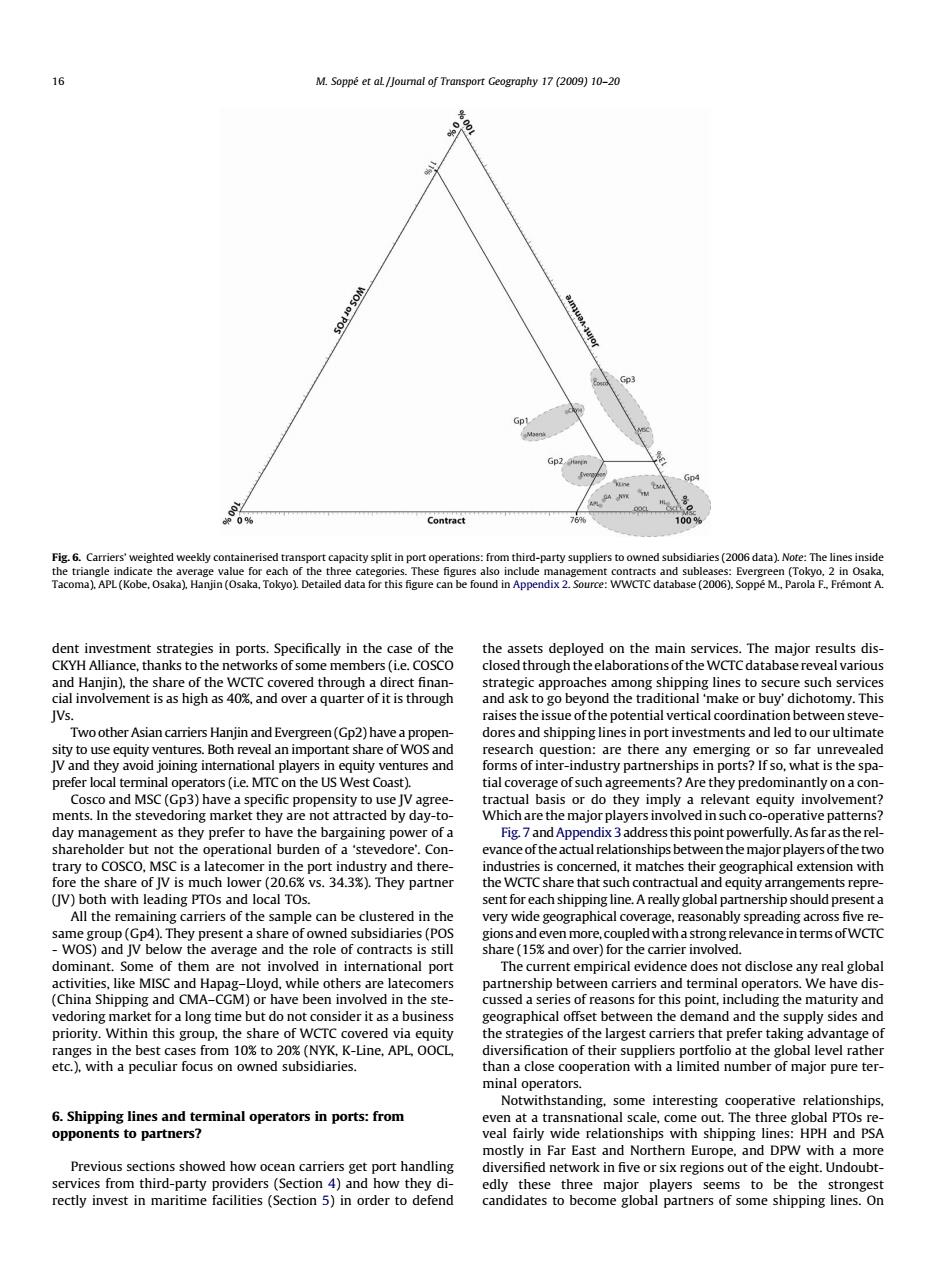

16 M.Soppe et aL/Joumal of Transport Geography 17(2009)10-20 SOd o SOM Gp2. Contract 1000 Fig.6.Carriers'weighted weekly containerised transport capacity split in port operations:from third-party suppliers to owned subsidiaries(2006 data).Note:The lines inside the triangle indicate the average value for each of the three categories.These figures also include management contracts and subleases:Evergreen (Tokyo,2 in Osaka. Tacoma).APL(Kobe,Osaka).Hanjin(Osaka,Tokyo)Detailed data for this figure can be found in Appendix 2.Source:WWCTC database(2006).Soppe M.,Parola F..Fremont A. dent investment strategies in ports.Specifically in the case of the the assets deployed on the main services.The major results dis- CKYH Alliance,thanks to the networks of some members(i.e.COSCO closed through the elaborations of the WCTC database reveal various and Hanjin).the share of the WCTC covered through a direct finan- strategic approaches among shipping lines to secure such services cial involvement is as high as 40%,and over a quarter of it is through and ask to go beyond the traditional'make or buy'dichotomy.This JVs. raises the issue of the potential vertical coordination between steve- Two other Asian carriers Hanjin and Evergreen(Gp2)have a propen- dores and shipping lines in port investments and led to our ultimate sity to use equity ventures.Both reveal an important share of WOS and research question:are there any emerging or so far unrevealed JV and they avoid joining international players in equity ventures and forms of inter-industry partnerships in ports?If so,what is the spa- prefer local terminal operators(i.e.MTC on the US West Coast). tial coverage of such agreements?Are they predominantly on a con- Cosco and MSC(Gp3)have a specific propensity to use JV agree- tractual basis or do they imply a relevant equity involvement? ments.In the stevedoring market they are not attracted by day-to- Which are the major players involved in such co-operative patterns? day management as they prefer to have the bargaining power of a Fig 7 and Appendix 3 address this point powerfully.As far as the rel- shareholder but not the operational burden of a'stevedore'.Con- evance of the actual relationships between the major players of the two trary to COSCO,MSC is a latecomer in the port industry and there- industries is concerned,it matches their geographical extension with fore the share of JV is much lower(20.6%vs.34.3%).They partner the WCTC share that such contractual and equity arrangements repre- (JV)both with leading PTOs and local TOs. sent for each shipping line.A really global partnership should present a All the remaining carriers of the sample can be clustered in the very wide geographical coverage,reasonably spreading across five re- same group(Gp4).They present a share of owned subsidiaries(POS gions and even more,coupled with a strong relevance in terms ofWCTO WOS)and JV below the average and the role of contracts is still share (15%and over)for the carrier involved. dominant.Some of them are not involved in international port The current empirical evidence does not disclose any real global activities,like MISC and Hapag-Lloyd,while others are latecomers partnership between carriers and terminal operators.We have dis- (China Shipping and CMA-CGM)or have been involved in the ste- cussed a series of reasons for this point,including the maturity and vedoring market for a long time but do not consider it as a business geographical offset between the demand and the supply sides and priority.Within this group,the share of WCTC covered via equity the strategies of the largest carriers that prefer taking advantage of ranges in the best cases from 10%to 20%(NYK,K-Line,APL OOCL diversification of their suppliers portfolio at the global level rather etc.)with a peculiar focus on owned subsidiaries. than a close cooperation with a limited number of major pure ter- minal operators. Notwithstanding,some interesting cooperative relationships 6.Shipping lines and terminal operators in ports:from even at a transnational scale,come out.The three global PTOs re- opponents to partners? veal fairly wide relationships with shipping lines:HPH and PSA mostly in Far East and Northern Europe,and DPW with a more Previous sections showed how ocean carriers get port handling diversified network in five or six regions out of the eight.Undoubt- services from third-party providers (Section 4)and how they di- edly these three major players seems to be the strongest rectly invest in maritime facilities (Section 5)in order to defend candidates to become global partners of some shipping lines.Ondent investment strategies in ports. Specifically in the case of the CKYH Alliance, thanks to the networks of some members (i.e. COSCO and Hanjin), the share of the WCTC covered through a direct financial involvement is as high as 40%, and over a quarter of it is through JVs. Two other Asian carriers Hanjin and Evergreen (Gp2) have a propensity to use equity ventures. Both reveal an important share of WOS and JV and they avoid joining international players in equity ventures and prefer local terminal operators (i.e. MTC on the US West Coast). Cosco and MSC (Gp3) have a specific propensity to use JV agreements. In the stevedoring market they are not attracted by day-today management as they prefer to have the bargaining power of a shareholder but not the operational burden of a ‘stevedore’. Contrary to COSCO, MSC is a latecomer in the port industry and therefore the share of JV is much lower (20.6% vs. 34.3%). They partner (JV) both with leading PTOs and local TOs. All the remaining carriers of the sample can be clustered in the same group (Gp4). They present a share of owned subsidiaries (POS - WOS) and JV below the average and the role of contracts is still dominant. Some of them are not involved in international port activities, like MISC and Hapag–Lloyd, while others are latecomers (China Shipping and CMA–CGM) or have been involved in the stevedoring market for a long time but do not consider it as a business priority. Within this group, the share of WCTC covered via equity ranges in the best cases from 10% to 20% (NYK, K-Line, APL, OOCL, etc.), with a peculiar focus on owned subsidiaries. 6. Shipping lines and terminal operators in ports: from opponents to partners? Previous sections showed how ocean carriers get port handling services from third-party providers (Section 4) and how they directly invest in maritime facilities (Section 5) in order to defend the assets deployed on the main services. The major results disclosed through the elaborations of theWCTC database reveal various strategic approaches among shipping lines to secure such services and ask to go beyond the traditional ‘make or buy’ dichotomy. This raises the issue of the potential vertical coordination between stevedores and shipping lines in port investments and led to our ultimate research question: are there any emerging or so far unrevealed forms of inter-industry partnerships in ports? If so, what is the spatial coverage of such agreements? Are they predominantly on a contractual basis or do they imply a relevant equity involvement? Which are the major players involved in such co-operative patterns? Fig. 7andAppendix 3address this point powerfully. As far as the relevance of the actual relationships between themajor players of the two industries is concerned, it matches their geographical extension with the WCTC share that such contractual and equity arrangements represent for each shipping line. A really global partnership should present a very wide geographical coverage, reasonably spreading across five regions and evenmore, coupledwith a strong relevance in terms ofWCTC share (15% and over) for the carrier involved. The current empirical evidence does not disclose any real global partnership between carriers and terminal operators. We have discussed a series of reasons for this point, including the maturity and geographical offset between the demand and the supply sides and the strategies of the largest carriers that prefer taking advantage of diversification of their suppliers portfolio at the global level rather than a close cooperation with a limited number of major pure terminal operators. Notwithstanding, some interesting cooperative relationships, even at a transnational scale, come out. The three global PTOs reveal fairly wide relationships with shipping lines: HPH and PSA mostly in Far East and Northern Europe, and DPW with a more diversified network in five or six regions out of the eight. Undoubtedly these three major players seems to be the strongest candidates to become global partners of some shipping lines. On Fig. 6. Carriers’ weighted weekly containerised transport capacity split in port operations: from third-party suppliers to owned subsidiaries (2006 data). Note: The lines inside the triangle indicate the average value for each of the three categories. These figures also include management contracts and subleases: Evergreen (Tokyo, 2 in Osaka, Tacoma), APL (Kobe, Osaka), Hanjin (Osaka, Tokyo). Detailed data for this figure can be found in Appendix 2. Source: WWCTC database (2006), Soppé M., Parola F., Frémont A. 16 M. Soppé et al. / Journal of Transport Geography 17 (2009) 10–20