正在加载图片...

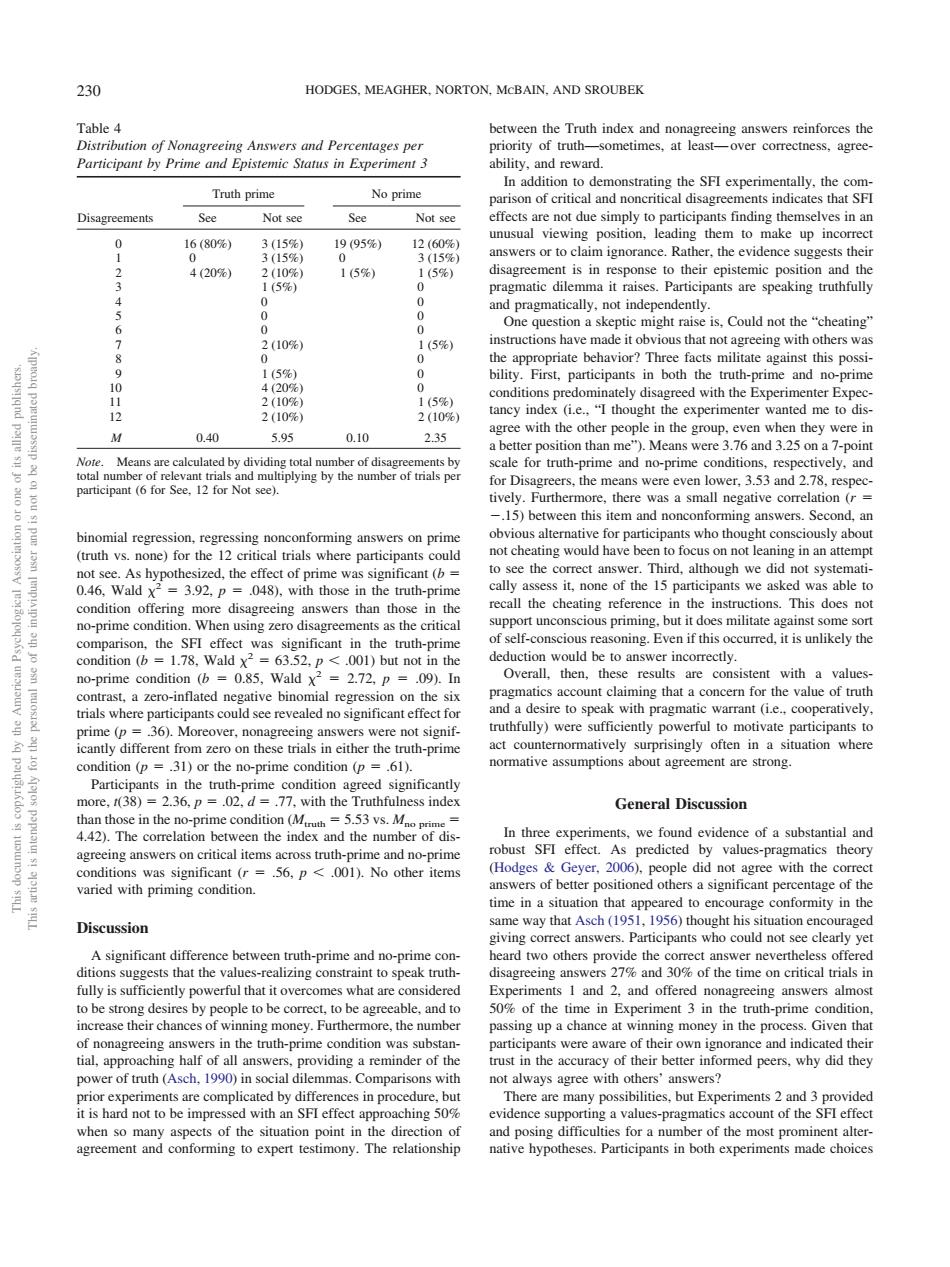

230 HODGES.MEAGHER.NORTON,MCBAIN.AND SROUBEK Table4 over correctness.agree rard In addition to dem Truth prime No prime asiningthesHcapcimeni.t See Not see Not see 16(80%) 19(95%) 4(20%) 5% 1(5%) Participants are speaking truthfully 210% (5) First.participants in both the truth-prime and no 210%) 0.40 5.95 0.10 cale for truth-prime and no-prime conditio 3.53 and 15)between this item and nonconfom ne answers.Seco a binomial ree regressing nonconforming answerson prim abou ruth vs ne)lor t the ans 46 ).with thosein the truth-prime h in the inst This do ld be to ansy Ove ifin on 36).Moreover.nonagreeing ers were not signif y)were sul ro on the r th ith-prime normative assumptions about agreement are strong. Parti ts the truth-prim agreed ss index General Discussion the The corelation between the index and the number ofd onditions was sienificant No other items Hodges of berever. did with the co varied with priming condition time in a si age conformity in th Discussion ay th re ments and 2 and offered po ing answers almos rs in the truth-prime dition w of their own orance and inc ated thei al- app idingare of the med peers.why did they but Experiments2and3 nce agreement and conforming to expert testimony.The relationship native hypotheses.Participants in both experiments made choicesbinomial regression, regressing nonconforming answers on prime (truth vs. none) for the 12 critical trials where participants could not see. As hypothesized, the effect of prime was significant (b 0.46, Wald 2 3.92, p .048), with those in the truth-prime condition offering more disagreeing answers than those in the no-prime condition. When using zero disagreements as the critical comparison, the SFI effect was significant in the truth-prime condition (b 1.78, Wald 2 63.52, p .001) but not in the no-prime condition (b 0.85, Wald 2 2.72, p .09). In contrast, a zero-inflated negative binomial regression on the six trials where participants could see revealed no significant effect for prime (p .36). Moreover, nonagreeing answers were not significantly different from zero on these trials in either the truth-prime condition (p .31) or the no-prime condition (p .61). Participants in the truth-prime condition agreed significantly more, t(38) 2.36, p .02, d .77, with the Truthfulness index than those in the no-prime condition (Mtruth 5.53 vs. Mno prime 4.42). The correlation between the index and the number of disagreeing answers on critical items across truth-prime and no-prime conditions was significant (r .56, p .001). No other items varied with priming condition. Discussion A significant difference between truth-prime and no-prime conditions suggests that the values-realizing constraint to speak truthfully is sufficiently powerful that it overcomes what are considered to be strong desires by people to be correct, to be agreeable, and to increase their chances of winning money. Furthermore, the number of nonagreeing answers in the truth-prime condition was substantial, approaching half of all answers, providing a reminder of the power of truth (Asch, 1990) in social dilemmas. Comparisons with prior experiments are complicated by differences in procedure, but it is hard not to be impressed with an SFI effect approaching 50% when so many aspects of the situation point in the direction of agreement and conforming to expert testimony. The relationship between the Truth index and nonagreeing answers reinforces the priority of truth—sometimes, at least— over correctness, agreeability, and reward. In addition to demonstrating the SFI experimentally, the comparison of critical and noncritical disagreements indicates that SFI effects are not due simply to participants finding themselves in an unusual viewing position, leading them to make up incorrect answers or to claim ignorance. Rather, the evidence suggests their disagreement is in response to their epistemic position and the pragmatic dilemma it raises. Participants are speaking truthfully and pragmatically, not independently. One question a skeptic might raise is, Could not the “cheating” instructions have made it obvious that not agreeing with others was the appropriate behavior? Three facts militate against this possibility. First, participants in both the truth-prime and no-prime conditions predominately disagreed with the Experimenter Expectancy index (i.e., “I thought the experimenter wanted me to disagree with the other people in the group, even when they were in a better position than me”). Means were 3.76 and 3.25 on a 7-point scale for truth-prime and no-prime conditions, respectively, and for Disagreers, the means were even lower, 3.53 and 2.78, respectively. Furthermore, there was a small negative correlation (r .15) between this item and nonconforming answers. Second, an obvious alternative for participants who thought consciously about not cheating would have been to focus on not leaning in an attempt to see the correct answer. Third, although we did not systematically assess it, none of the 15 participants we asked was able to recall the cheating reference in the instructions. This does not support unconscious priming, but it does militate against some sort of self-conscious reasoning. Even if this occurred, it is unlikely the deduction would be to answer incorrectly. Overall, then, these results are consistent with a valuespragmatics account claiming that a concern for the value of truth and a desire to speak with pragmatic warrant (i.e., cooperatively, truthfully) were sufficiently powerful to motivate participants to act counternormatively surprisingly often in a situation where normative assumptions about agreement are strong. General Discussion In three experiments, we found evidence of a substantial and robust SFI effect. As predicted by values-pragmatics theory (Hodges & Geyer, 2006), people did not agree with the correct answers of better positioned others a significant percentage of the time in a situation that appeared to encourage conformity in the same way that Asch (1951, 1956) thought his situation encouraged giving correct answers. Participants who could not see clearly yet heard two others provide the correct answer nevertheless offered disagreeing answers 27% and 30% of the time on critical trials in Experiments 1 and 2, and offered nonagreeing answers almost 50% of the time in Experiment 3 in the truth-prime condition, passing up a chance at winning money in the process. Given that participants were aware of their own ignorance and indicated their trust in the accuracy of their better informed peers, why did they not always agree with others’ answers? There are many possibilities, but Experiments 2 and 3 provided evidence supporting a values-pragmatics account of the SFI effect and posing difficulties for a number of the most prominent alternative hypotheses. Participants in both experiments made choices Table 4 Distribution of Nonagreeing Answers and Percentages per Participant by Prime and Epistemic Status in Experiment 3 Truth prime No prime Disagreements See Not see See Not see 0 16 (80%) 3 (15%) 19 (95%) 12 (60%) 1 0 3 (15%) 0 3 (15%) 2 4 (20%) 2 (10%) 1 (5%) 1 (5%) 3 1 (5%) 0 40 0 50 0 60 0 7 2 (10%) 1 (5%) 80 0 9 1 (5%) 0 10 4 (20%) 0 11 2 (10%) 1 (5%) 12 2 (10%) 2 (10%) M 0.40 5.95 0.10 2.35 Note. Means are calculated by dividing total number of disagreements by total number of relevant trials and multiplying by the number of trials per participant (6 for See, 12 for Not see). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 230 HODGES, MEAGHER, NORTON, MCBAIN, AND SROUBEK���������������������