正在加载图片...

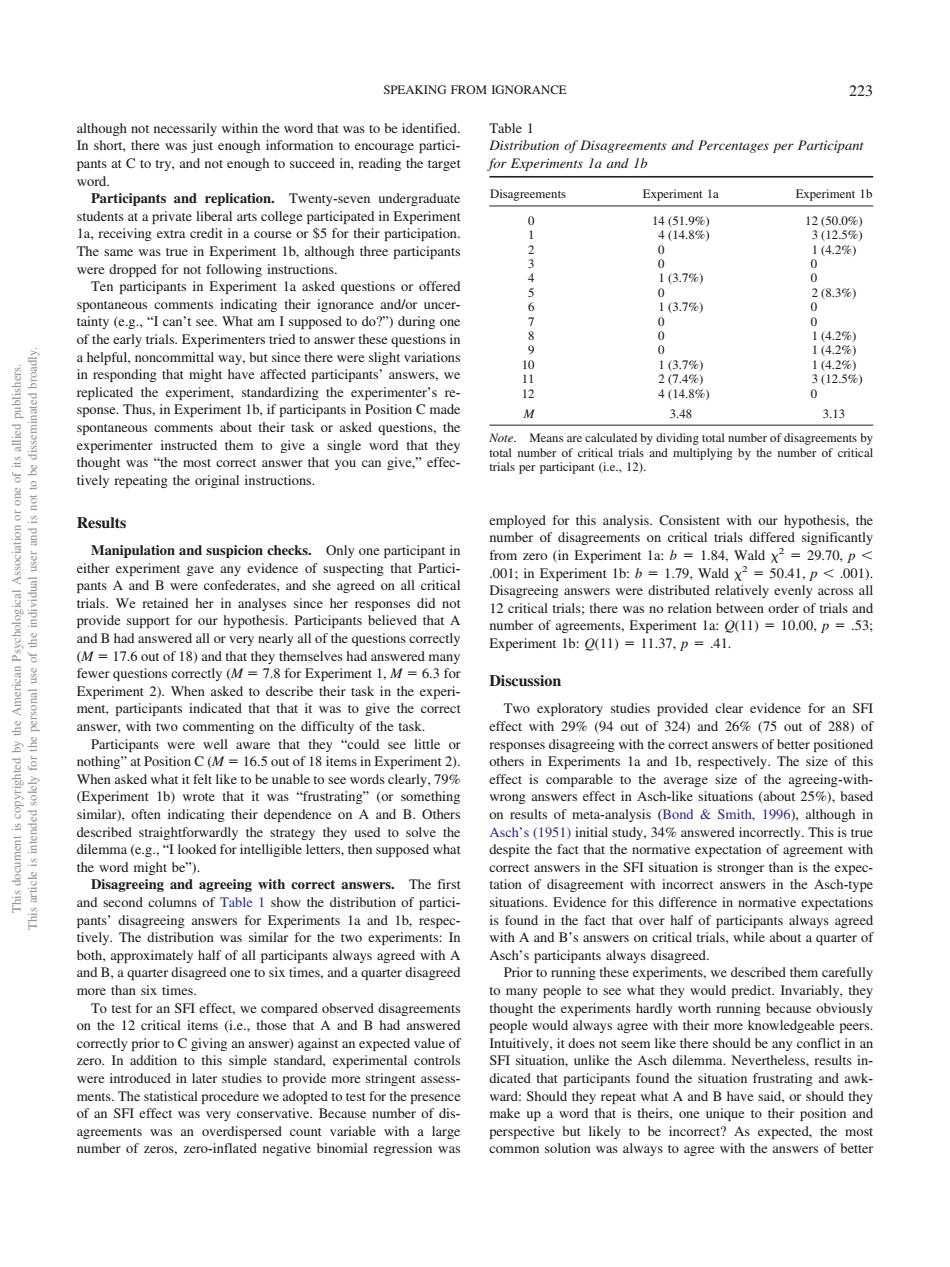

SPEAKING FROM IGNORANCE 223 Table f and Percentages per Participant try,and not enou to succeed in reading the targe for Experiments la and Ib Disagreements Experiment la Experiment Ib ipated in Experim 142 edropped for not follo ing 7% comments indicating their igne 283%) 3.7% y (cg What ar e there were slight variation 90 ve affected answers 3.13 give a word that ght was "th wer that you can give,"effee tively repeating th Results mploved for this analysis.Consistent with our hypothesis.the umber of Manipulation and suspicion checks. Only one p nt ir gave ss al We retain d he n analyses since her d )137()1000.3 nts.Exp imen 2).When Discussion asked to dese indicate Parti are that es- ne EXp nd Ib The siz hat it fa It like to b 70 riment 1b) r that it was"frustrating”(or wrong answers effect in Asch-like ituati a(e.."looked for intelligible ette then supposed what ve expectation of agreement with eing and agre ers.The firs partic tions.E n normative expectati The for the two exp ith A and Be ansy ve deserihed them e than six time nany people to see what they would predict.Invariably.they vere introduced in later studies to provide more strineent asses e statistical procedure we a vard:Sh d the nat A and as an ov ersed ut likely to be in orrect?As ted,the mos umber ofesero-inflated negative binomial regression was common solution was always to agree with the answers of b bette although not necessarily within the word that was to be identified. In short, there was just enough information to encourage participants at C to try, and not enough to succeed in, reading the target word. Participants and replication. Twenty-seven undergraduate students at a private liberal arts college participated in Experiment 1a, receiving extra credit in a course or $5 for their participation. The same was true in Experiment 1b, although three participants were dropped for not following instructions. Ten participants in Experiment 1a asked questions or offered spontaneous comments indicating their ignorance and/or uncertainty (e.g., “I can’t see. What am I supposed to do?”) during one of the early trials. Experimenters tried to answer these questions in a helpful, noncommittal way, but since there were slight variations in responding that might have affected participants’ answers, we replicated the experiment, standardizing the experimenter’s response. Thus, in Experiment 1b, if participants in Position C made spontaneous comments about their task or asked questions, the experimenter instructed them to give a single word that they thought was “the most correct answer that you can give,” effectively repeating the original instructions. Results Manipulation and suspicion checks. Only one participant in either experiment gave any evidence of suspecting that Participants A and B were confederates, and she agreed on all critical trials. We retained her in analyses since her responses did not provide support for our hypothesis. Participants believed that A and B had answered all or very nearly all of the questions correctly (M 17.6 out of 18) and that they themselves had answered many fewer questions correctly (M 7.8 for Experiment 1, M 6.3 for Experiment 2). When asked to describe their task in the experiment, participants indicated that that it was to give the correct answer, with two commenting on the difficulty of the task. Participants were well aware that they “could see little or nothing” at Position C (M 16.5 out of 18 items in Experiment 2). When asked what it felt like to be unable to see words clearly, 79% (Experiment 1b) wrote that it was “frustrating” (or something similar), often indicating their dependence on A and B. Others described straightforwardly the strategy they used to solve the dilemma (e.g., “I looked for intelligible letters, then supposed what the word might be”). Disagreeing and agreeing with correct answers. The first and second columns of Table 1 show the distribution of participants’ disagreeing answers for Experiments 1a and 1b, respectively. The distribution was similar for the two experiments: In both, approximately half of all participants always agreed with A and B, a quarter disagreed one to six times, and a quarter disagreed more than six times. To test for an SFI effect, we compared observed disagreements on the 12 critical items (i.e., those that A and B had answered correctly prior to C giving an answer) against an expected value of zero. In addition to this simple standard, experimental controls were introduced in later studies to provide more stringent assessments. The statistical procedure we adopted to test for the presence of an SFI effect was very conservative. Because number of disagreements was an overdispersed count variable with a large number of zeros, zero-inflated negative binomial regression was employed for this analysis. Consistent with our hypothesis, the number of disagreements on critical trials differed significantly from zero (in Experiment 1a: b 1.84, Wald 2 29.70, p .001; in Experiment 1b: b 1.79, Wald 2 50.41, p .001). Disagreeing answers were distributed relatively evenly across all 12 critical trials; there was no relation between order of trials and number of agreements, Experiment 1a: Q(11) 10.00, p .53; Experiment 1b: Q(11) 11.37, p .41. Discussion Two exploratory studies provided clear evidence for an SFI effect with 29% (94 out of 324) and 26% (75 out of 288) of responses disagreeing with the correct answers of better positioned others in Experiments 1a and 1b, respectively. The size of this effect is comparable to the average size of the agreeing-withwrong answers effect in Asch-like situations (about 25%), based on results of meta-analysis (Bond & Smith, 1996), although in Asch’s (1951) initial study, 34% answered incorrectly. This is true despite the fact that the normative expectation of agreement with correct answers in the SFI situation is stronger than is the expectation of disagreement with incorrect answers in the Asch-type situations. Evidence for this difference in normative expectations is found in the fact that over half of participants always agreed with A and B’s answers on critical trials, while about a quarter of Asch’s participants always disagreed. Prior to running these experiments, we described them carefully to many people to see what they would predict. Invariably, they thought the experiments hardly worth running because obviously people would always agree with their more knowledgeable peers. Intuitively, it does not seem like there should be any conflict in an SFI situation, unlike the Asch dilemma. Nevertheless, results indicated that participants found the situation frustrating and awkward: Should they repeat what A and B have said, or should they make up a word that is theirs, one unique to their position and perspective but likely to be incorrect? As expected, the most common solution was always to agree with the answers of better Table 1 Distribution of Disagreements and Percentages per Participant for Experiments 1a and 1b Disagreements Experiment 1a Experiment 1b 0 14 (51.9%) 12 (50.0%) 1 4 (14.8%) 3 (12.5%) 2 0 1 (4.2%) 30 0 4 1 (3.7%) 0 5 0 2 (8.3%) 6 1 (3.7%) 0 70 0 8 0 1 (4.2%) 9 0 1 (4.2%) 10 1 (3.7%) 1 (4.2%) 11 2 (7.4%) 3 (12.5%) 12 4 (14.8%) 0 M 3.48 3.13 Note. Means are calculated by dividing total number of disagreements by total number of critical trials and multiplying by the number of critical trials per participant (i.e., 12). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. SPEAKING FROM IGNORANCE 223��������������