正在加载图片...

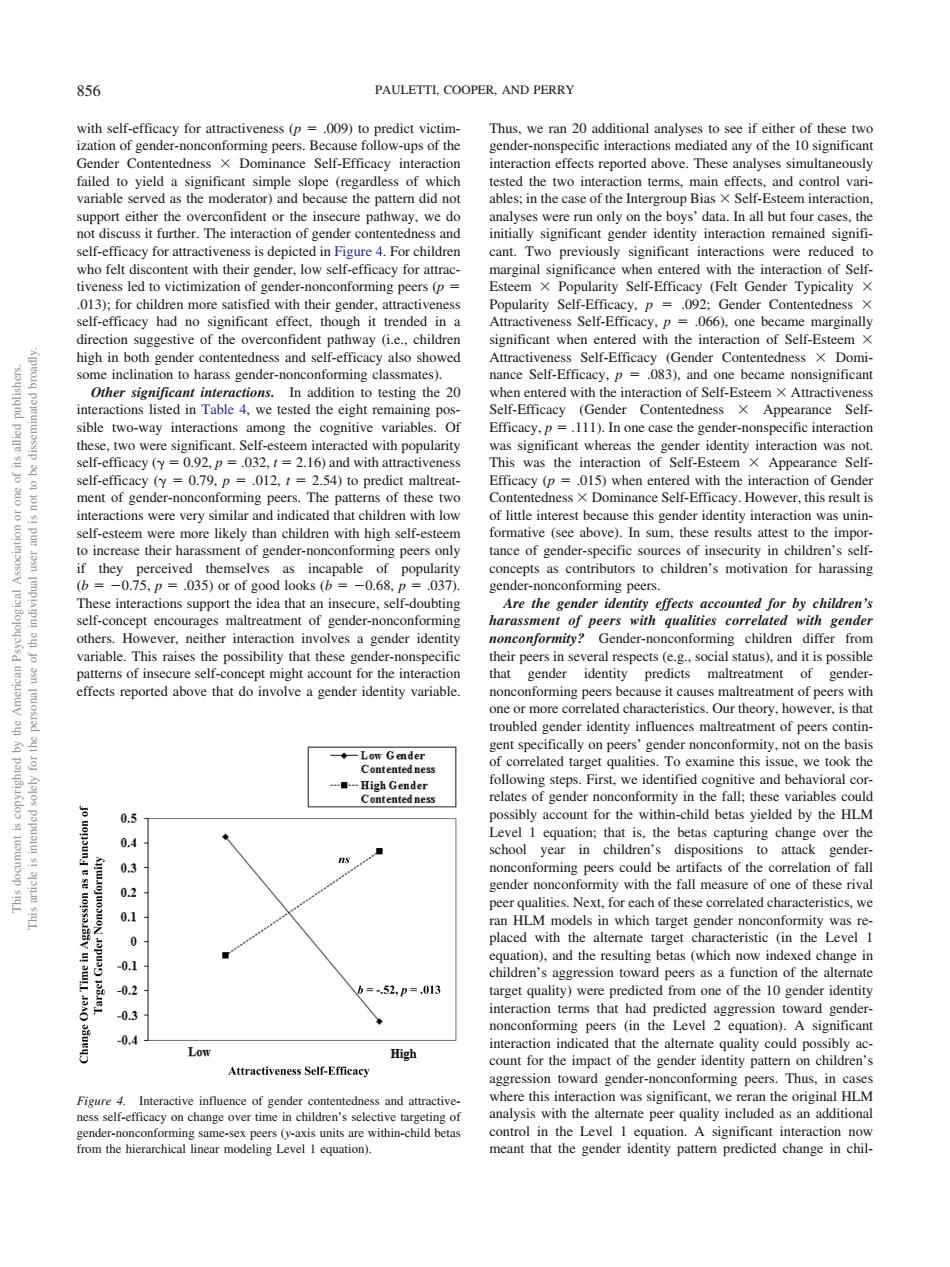

PAULETTL COOPER.AND PERRY hself-efficacy for (p) Self-Efficac orted abov yiek ope nd c upport either the confident or the we do re run only on the bovs In all but four For chil- marginal with the 13):for children more satisfied with their gender,attracti Popularity Self-Fff .092: Gender Conte tedne fficacy had no ss Self-Eff dith he) igh in both ntedness and self-effica Self-Emcacy (Gender Contentedne s gen cy.p 3 2 po Sel-Emc p way inte acy.p efficacy (Y=0.92.p= interaction Self-Est The Con cl-E very sim ted th his gender identity child their h of urity 027 inte pport the idea that an self-do re the gend effects ccounted for by children' 9 ab possibility that these gender ral respec ssibl e that do involye a gender identity variable ning peers on D Low Gemder s of o all-th 05 ◆ yea children' dispositio ender nonco rmity with the fall measu of one of the 0.1 with th evel of the 82 b=-52.p-.013 target quality)were predicted from one of the 10 gender identity 01 -04 High action venes Sclf-Efficacy on toward eender-nonconformine peers Thus.in Figure 4.Interactive influence of gender s ntentedne n was significant,we self-effic ontrol in the Lev ficant interaction near mod ling Level I equation) with self-efficacy for attractiveness (p .009) to predict victimization of gender-nonconforming peers. Because follow-ups of the Gender Contentedness Dominance Self-Efficacy interaction failed to yield a significant simple slope (regardless of which variable served as the moderator) and because the pattern did not support either the overconfident or the insecure pathway, we do not discuss it further. The interaction of gender contentedness and self-efficacy for attractiveness is depicted in Figure 4. For children who felt discontent with their gender, low self-efficacy for attractiveness led to victimization of gender-nonconforming peers (p .013); for children more satisfied with their gender, attractiveness self-efficacy had no significant effect, though it trended in a direction suggestive of the overconfident pathway (i.e., children high in both gender contentedness and self-efficacy also showed some inclination to harass gender-nonconforming classmates). Other significant interactions. In addition to testing the 20 interactions listed in Table 4, we tested the eight remaining possible two-way interactions among the cognitive variables. Of these, two were significant. Self-esteem interacted with popularity self-efficacy ( 0.92, p .032, t 2.16) and with attractiveness self-efficacy ( 0.79, p .012, t 2.54) to predict maltreatment of gender-nonconforming peers. The patterns of these two interactions were very similar and indicated that children with low self-esteem were more likely than children with high self-esteem to increase their harassment of gender-nonconforming peers only if they perceived themselves as incapable of popularity (b 0.75, p .035) or of good looks (b 0.68, p .037). These interactions support the idea that an insecure, self-doubting self-concept encourages maltreatment of gender-nonconforming others. However, neither interaction involves a gender identity variable. This raises the possibility that these gender-nonspecific patterns of insecure self-concept might account for the interaction effects reported above that do involve a gender identity variable. Thus, we ran 20 additional analyses to see if either of these two gender-nonspecific interactions mediated any of the 10 significant interaction effects reported above. These analyses simultaneously tested the two interaction terms, main effects, and control variables; in the case of the Intergroup Bias Self-Esteem interaction, analyses were run only on the boys’ data. In all but four cases, the initially significant gender identity interaction remained significant. Two previously significant interactions were reduced to marginal significance when entered with the interaction of SelfEsteem Popularity Self-Efficacy (Felt Gender Typicality Popularity Self-Efficacy, p .092; Gender Contentedness Attractiveness Self-Efficacy, p .066), one became marginally significant when entered with the interaction of Self-Esteem Attractiveness Self-Efficacy (Gender Contentedness Dominance Self-Efficacy, p .083), and one became nonsignificant when entered with the interaction of Self-Esteem Attractiveness Self-Efficacy (Gender Contentedness Appearance SelfEfficacy, p .111). In one case the gender-nonspecific interaction was significant whereas the gender identity interaction was not. This was the interaction of Self-Esteem Appearance SelfEfficacy (p .015) when entered with the interaction of Gender Contentedness Dominance Self-Efficacy. However, this result is of little interest because this gender identity interaction was uninformative (see above). In sum, these results attest to the importance of gender-specific sources of insecurity in children’s selfconcepts as contributors to children’s motivation for harassing gender-nonconforming peers. Are the gender identity effects accounted for by children’s harassment of peers with qualities correlated with gender nonconformity? Gender-nonconforming children differ from their peers in several respects (e.g., social status), and it is possible that gender identity predicts maltreatment of gendernonconforming peers because it causes maltreatment of peers with one or more correlated characteristics. Our theory, however, is that troubled gender identity influences maltreatment of peers contingent specifically on peers’ gender nonconformity, not on the basis of correlated target qualities. To examine this issue, we took the following steps. First, we identified cognitive and behavioral correlates of gender nonconformity in the fall; these variables could possibly account for the within-child betas yielded by the HLM Level 1 equation; that is, the betas capturing change over the school year in children’s dispositions to attack gendernonconforming peers could be artifacts of the correlation of fall gender nonconformity with the fall measure of one of these rival peer qualities. Next, for each of these correlated characteristics, we ran HLM models in which target gender nonconformity was replaced with the alternate target characteristic (in the Level 1 equation), and the resulting betas (which now indexed change in children’s aggression toward peers as a function of the alternate target quality) were predicted from one of the 10 gender identity interaction terms that had predicted aggression toward gendernonconforming peers (in the Level 2 equation). A significant interaction indicated that the alternate quality could possibly account for the impact of the gender identity pattern on children’s aggression toward gender-nonconforming peers. Thus, in cases where this interaction was significant, we reran the original HLM analysis with the alternate peer quality included as an additional control in the Level 1 equation. A significant interaction now meant that the gender identity pattern predicted change in chilFigure 4. Interactive influence of gender contentedness and attractiveness self-efficacy on change over time in children’s selective targeting of gender-nonconforming same-sex peers (y-axis units are within-child betas from the hierarchical linear modeling Level 1 equation). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 856 PAULETTI, COOPER, AND PERRY�������������������