正在加载图片...

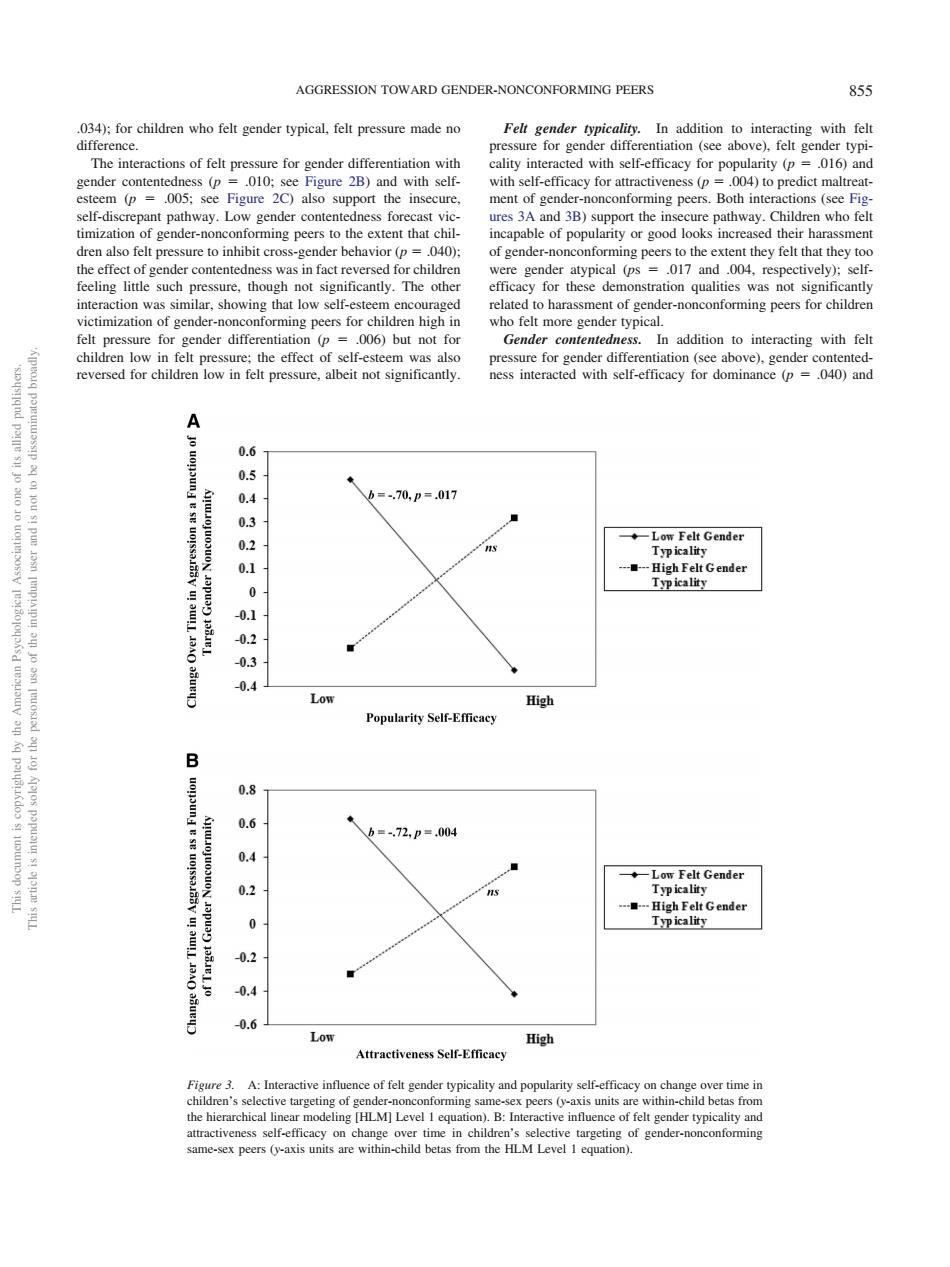

AGGRESSION TOWARD GENDER-NONCONFORMING PEERS 855 u咖佳pee mol Felt gender typicality.In addition to interacting with felt tions of felt differentiation with ton (see ender content ss (p 010 2B)an with self h efficacy for attractiv ness (n 04)to predict maltrea and 3B)s the pee of gender-noncon rming peers to the extent that pable of populanty or good looks increas sed he men was in fact reversed for childre 017 and 004 respectively self eling little ho e f the tion qua ictimization of gend who felt moregend ypica der differ 006)but not reversed for children ow in felt pressure albeit not significantly. self-efficacy for dominance(p4)and =-70,p=.017 Low Felt Gender High Popularity Self-Efficacy .004 Felt Gender Autractiveness Self-Efficacy High he hie [HLM]Level 1 equa of felt.034); for children who felt gender typical, felt pressure made no difference. The interactions of felt pressure for gender differentiation with gender contentedness (p .010; see Figure 2B) and with selfesteem (p .005; see Figure 2C) also support the insecure, self-discrepant pathway. Low gender contentedness forecast victimization of gender-nonconforming peers to the extent that children also felt pressure to inhibit cross-gender behavior (p .040); the effect of gender contentedness was in fact reversed for children feeling little such pressure, though not significantly. The other interaction was similar, showing that low self-esteem encouraged victimization of gender-nonconforming peers for children high in felt pressure for gender differentiation (p .006) but not for children low in felt pressure; the effect of self-esteem was also reversed for children low in felt pressure, albeit not significantly. Felt gender typicality. In addition to interacting with felt pressure for gender differentiation (see above), felt gender typicality interacted with self-efficacy for popularity (p .016) and with self-efficacy for attractiveness (p .004) to predict maltreatment of gender-nonconforming peers. Both interactions (see Figures 3A and 3B) support the insecure pathway. Children who felt incapable of popularity or good looks increased their harassment of gender-nonconforming peers to the extent they felt that they too were gender atypical (ps .017 and .004, respectively); selfefficacy for these demonstration qualities was not significantly related to harassment of gender-nonconforming peers for children who felt more gender typical. Gender contentedness. In addition to interacting with felt pressure for gender differentiation (see above), gender contentedness interacted with self-efficacy for dominance (p .040) and Figure 3. A: Interactive influence of felt gender typicality and popularity self-efficacy on change over time in children’s selective targeting of gender-nonconforming same-sex peers (y-axis units are within-child betas from the hierarchical linear modeling [HLM] Level 1 equation). B: Interactive influence of felt gender typicality and attractiveness self-efficacy on change over time in children’s selective targeting of gender-nonconforming same-sex peers (y-axis units are within-child betas from the HLM Level 1 equation). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. AGGRESSION TOWARD GENDER-NONCONFORMING PEERS 855��������