正在加载图片...

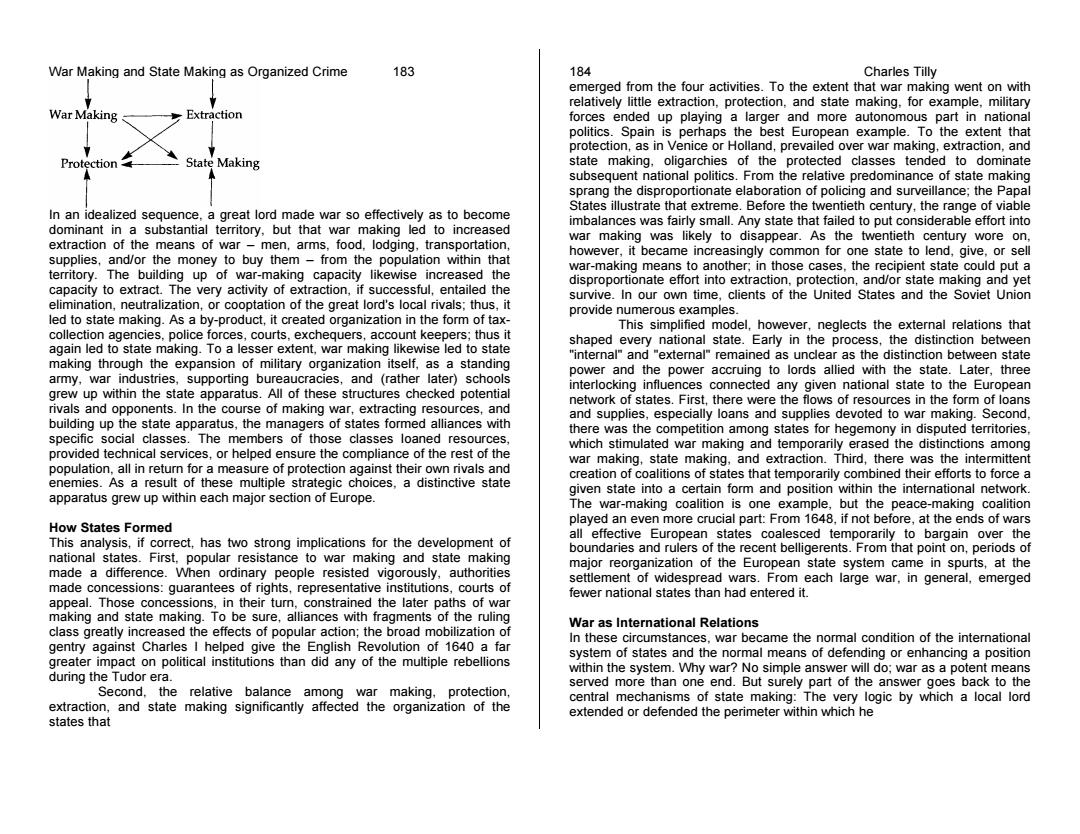

War Making and State Making as Organized Crime 183 184 Charles Tilly emerged from the four activities.To the extent that war making went on with relatively little extraction,protection,and state making,for example,military War Making Extraction forces ended up playing a larger and more autonomous part in national politics.Spain is perhaps the best European example.To the extent that protection,as in Venice or Holland,prevailed over war making,extraction,and Protection State Making state making,oligarchies of the protected classes tended to dominate subsequent national politics.From the relative predominance of state making sprang the disproportionate elaboration of policing and surveillance;the Papal In an idealized sequence,a great lord made war so effectively as to become States illustrate that extreme.Before the twentieth century,the range of viable imbalances was fairly small.Any state that failed to put considerable effort into dominant in a substantial territory,but that war making led to increased extraction of the means of war-men,arms,food,lodging,transportation, war making was likely to disappear.As the twentieth century wore on, however,it became increasingly common for one state to lend,give,or sell supplies,and/or the money to buy them-from the population within that territory.The building up of war-making capacity likewise increased the war-making means to another;in those cases,the recipient state could put a disproportionate effort into extraction,protection,and/or state making and yet capacity to extract.The very activity of extraction,if successful,entailed the survive.In our own time,clients of the United States and the Soviet Union elimination,neutralization,or cooptation of the great lord's local rivals;thus,it provide numerous examples. led to state making.As a by-product,it created organization in the form of tax- This simplified model,however,neglects the external relations that collection agencies,police forces,courts,exchequers,account keepers;thus it shaped every national state.Early in the process,the distinction between again led to state making.To a lesser extent,war making likewise led to state making through the expansion of military organization itself,as a standing "internal"and "external"remained as unclear as the distinction between state army,war industries,supporting bureaucracies,and (rather later)schools power and the power accruing to lords allied with the state.Later,three grew up within the state apparatus.All of these structures checked potential interlocking influences connected any given national state to the European network of states.First,there were the flows of resources in the form of loans rivals and opponents.In the course of making war,extracting resources,and and supplies,especially loans and supplies devoted to war making.Second. building up the state apparatus,the managers of states formed alliances with there was the competition among states for hegemony in disputed territories. specific social classes.The members of those classes loaned resources, which stimulated war making and temporarily erased the distinctions among provided technical services,or helped ensure the compliance of the rest of the war making,state making,and extraction.Third,there was the intermittent population,all in return for a measure of protection against their own rivals and creation of coalitions of states that temporarily combined their efforts to force a enemies.As a result of these multiple strategic choices,a distinctive state given state into a certain form and position within the international network. apparatus grew up within each major section of Europe. The war-making coalition is one example,but the peace-making coalition How States Formed played an even more crucial part:From 1648,if not before,at the ends of wars This analysis,if correct,has two strong implications for the development of all effective European states coalesced temporarily to bargain over the boundaries and rulers of the recent belligerents.From that point on,periods of national states.First,popular resistance to war making and state making major reorganization of the European state system came in spurts,at the made a difference.When ordinary people resisted vigorously,authorities settlement of widespread wars.From each large war,in general,emerged made concessions:guarantees of rights,representative institutions,courts of fewer national states than had entered it. appeal.Those concessions,in their tum,constrained the later paths of war making and state making.To be sure,alliances with fragments of the ruling War as International Relations class greatly increased the effects of popular action;the broad mobilization of In these circumstances,war became the normal condition of the international gentry against Charles I helped give the English Revolution of 1640 a far greater impact on political institutions than did any of the multiple rebellions system of states and the normal means of defending or enhancing a position within the system.Why war?No simple answer will do;war as a potent means during the Tudor era. served more than one end.But surely part of the answer goes back to the Second,the relative balance among war making,protection, central mechanisms of state making:The very logic by which a local lord extraction,and state making significantly affected the organization of the extended or defended the perimeter within which he states thatWar Making and State Making as Organized Crime 183 In an idealized sequence, a great lord made war so effectively as to become dominant in a substantial territory, but that war making led to increased extraction of the means of war – men, arms, food, lodging, transportation, supplies, and/or the money to buy them – from the population within that territory. The building up of war-making capacity likewise increased the capacity to extract. The very activity of extraction, if successful, entailed the elimination, neutralization, or cooptation of the great lord's local rivals; thus, it led to state making. As a by-product, it created organization in the form of taxcollection agencies, police forces, courts, exchequers, account keepers; thus it again led to state making. To a lesser extent, war making likewise led to state making through the expansion of military organization itself, as a standing army, war industries, supporting bureaucracies, and (rather later) schools grew up within the state apparatus. All of these structures checked potential rivals and opponents. In the course of making war, extracting resources, and building up the state apparatus, the managers of states formed alliances with specific social classes. The members of those classes loaned resources, provided technical services, or helped ensure the compliance of the rest of the population, all in return for a measure of protection against their own rivals and enemies. As a result of these multiple strategic choices, a distinctive state apparatus grew up within each major section of Europe. How States Formed This analysis, if correct, has two strong implications for the development of national states. First, popular resistance to war making and state making made a difference. When ordinary people resisted vigorously, authorities made concessions: guarantees of rights, representative institutions, courts of appeal. Those concessions, in their turn, constrained the later paths of war making and state making. To be sure, alliances with fragments of the ruling class greatly increased the effects of popular action; the broad mobilization of gentry against Charles I helped give the English Revolution of 1640 a far greater impact on political institutions than did any of the multiple rebellions during the Tudor era. Second, the relative balance among war making, protection, extraction, and state making significantly affected the organization of the states that 184 Charles Tilly emerged from the four activities. To the extent that war making went on with relatively little extraction, protection, and state making, for example, military forces ended up playing a larger and more autonomous part in national politics. Spain is perhaps the best European example. To the extent that protection, as in Venice or Holland, prevailed over war making, extraction, and state making, oligarchies of the protected classes tended to dominate subsequent national politics. From the relative predominance of state making sprang the disproportionate elaboration of policing and surveillance; the Papal States illustrate that extreme. Before the twentieth century, the range of viable imbalances was fairly small. Any state that failed to put considerable effort into war making was likely to disappear. As the twentieth century wore on, however, it became increasingly common for one state to lend, give, or sell war-making means to another; in those cases, the recipient state could put a disproportionate effort into extraction, protection, and/or state making and yet survive. In our own time, clients of the United States and the Soviet Union provide numerous examples. This simplified model, however, neglects the external relations that shaped every national state. Early in the process, the distinction between "internal" and "external" remained as unclear as the distinction between state power and the power accruing to lords allied with the state. Later, three interlocking influences connected any given national state to the European network of states. First, there were the flows of resources in the form of loans and supplies, especially loans and supplies devoted to war making. Second, there was the competition among states for hegemony in disputed territories, which stimulated war making and temporarily erased the distinctions among war making, state making, and extraction. Third, there was the intermittent creation of coalitions of states that temporarily combined their efforts to force a given state into a certain form and position within the international network. The war-making coalition is one example, but the peace-making coalition played an even more crucial part: From 1648, if not before, at the ends of wars all effective European states coalesced temporarily to bargain over the boundaries and rulers of the recent belligerents. From that point on, periods of major reorganization of the European state system came in spurts, at the settlement of widespread wars. From each large war, in general, emerged fewer national states than had entered it. War as International Relations In these circumstances, war became the normal condition of the international system of states and the normal means of defending or enhancing a position within the system. Why war? No simple answer will do; war as a potent means served more than one end. But surely part of the answer goes back to the central mechanisms of state making: The very logic by which a local lord extended or defended the perimeter within which he