正在加载图片...

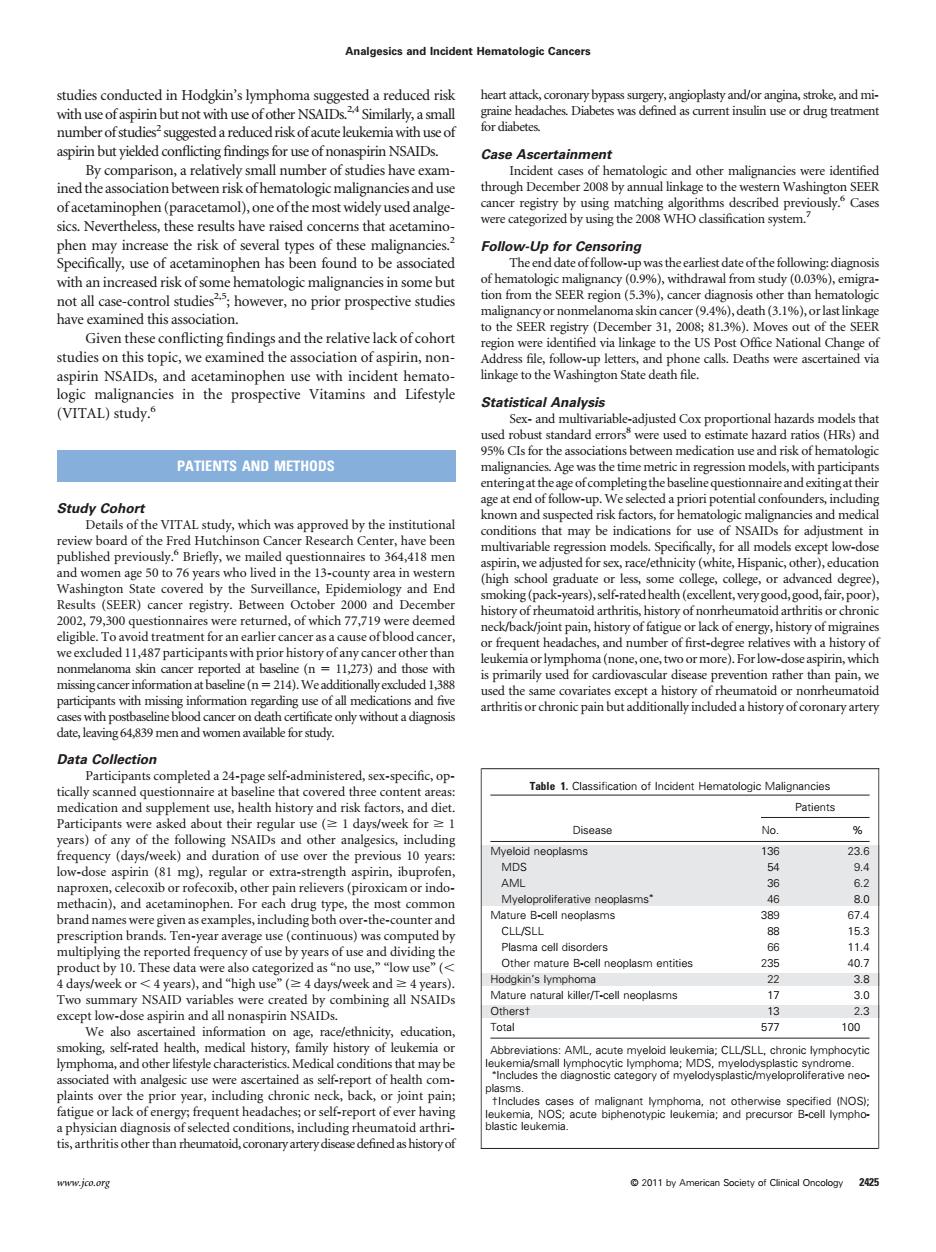

Analgesics and Incident Hematologic Cancers te wa n use or drug treatmer numbe By comparison.a relatively small umber of studies have am kage to th hrconcm产 Follow-Up for Ce )cancer di Given these conflicting findings and the relative lack of cohort the association of aspinn,non (VITAL)study. Statistical Analysis PATIENTS AND METHODS the time m he ne h partic Study Cohort which rd of the c ppro that may be indic ed for se the 13- c(he Hi v.Betw 2000 and De ,slfratedhealh(lexcaiy od good fai (SEER) ack ofer treatmcemtfor rasa the s id or nonrher Patients analgesics indudin 136 击一 a coll disorders n'ure neoplasm entities natural killer/T-cell neoplasms all nona 577 100 EE AML,acut s that m oronary artery dise 2011 by Amstudies conducted in Hodgkin’s lymphoma suggested a reduced risk with use of aspirin but not with use of other NSAIDs.2,4 Similarly, a small number of studies2 suggested a reduced risk of acuteleukemiawith use of aspirin but yielded conflicting findings for use of nonaspirin NSAIDs. By comparison, a relatively small number of studies have examined the association between risk of hematologicmalignancies and use of acetaminophen (paracetamol), one of the most widely used analgesics. Nevertheless, these results have raised concerns that acetaminophen may increase the risk of several types of these malignancies.2 Specifically, use of acetaminophen has been found to be associated with an increased risk of some hematologic malignancies in some but not all case-control studies2,5; however, no prior prospective studies have examined this association. Given these conflicting findings and the relative lack of cohort studies on this topic, we examined the association of aspirin, nonaspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen use with incident hematologic malignancies in the prospective Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) study.6 PATIENTS AND METHODS Study Cohort Details of the VITAL study, which was approved by the institutional review board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, have been published previously.6 Briefly, we mailed questionnaires to 364,418 men and women age 50 to 76 years who lived in the 13-county area in western Washington State covered by the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry. Between October 2000 and December 2002, 79,300 questionnaires were returned, of which 77,719 were deemed eligible. To avoid treatment for an earlier cancer as a cause of blood cancer, we excluded 11,487 participants with prior history of any cancer other than nonmelanoma skin cancer reported at baseline (n 11,273) and those with missing cancerinformation at baseline (n214).We additionally excluded 1,388 participants with missing information regarding use of all medications and five cases with postbaseline blood cancer on death certificate only without a diagnosis date, leaving 64,839 men and women available for study. Data Collection Participants completed a 24-page self-administered, sex-specific, optically scanned questionnaire at baseline that covered three content areas: medication and supplement use, health history and risk factors, and diet. Participants were asked about their regular use ( 1 days/week for 1 years) of any of the following NSAIDs and other analgesics, including frequency (days/week) and duration of use over the previous 10 years: low-dose aspirin (81 mg), regular or extra-strength aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib or rofecoxib, other pain relievers (piroxicam or indomethacin), and acetaminophen. For each drug type, the most common brand names were given as examples, including both over-the-counter and prescription brands. Ten-year average use (continuous) was computed by multiplying the reported frequency of use by years of use and dividing the product by 10. These data were also categorized as “no use,” “low use” ( 4 days/week or 4 years), and “high use” ( 4 days/week and 4 years). Two summary NSAID variables were created by combining all NSAIDs except low-dose aspirin and all nonaspirin NSAIDs. We also ascertained information on age, race/ethnicity, education, smoking, self-rated health, medical history, family history of leukemia or lymphoma, and other lifestyle characteristics. Medical conditions that may be associated with analgesic use were ascertained as self-report of health complaints over the prior year, including chronic neck, back, or joint pain; fatigue or lack of energy; frequent headaches; or self-report of ever having a physician diagnosis of selected conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, arthritis other than rheumatoid, coronary artery disease defined as history of heart attack, coronary bypass surgery, angioplasty and/or angina, stroke, and migraine headaches. Diabetes was defined as current insulin use or drug treatment for diabetes. Case Ascertainment Incident cases of hematologic and other malignancies were identified through December 2008 by annual linkage to the western Washington SEER cancer registry by using matching algorithms described previously.6 Cases were categorized by using the 2008 WHO classification system.7 Follow-Up for Censoring The end date offollow-upwas the earliest date of thefollowing: diagnosis of hematologic malignancy (0.9%), withdrawal from study (0.03%), emigration from the SEER region (5.3%), cancer diagnosis other than hematologic malignancy or nonmelanoma skin cancer (9.4%), death (3.1%), or last linkage to the SEER registry (December 31, 2008; 81.3%). Moves out of the SEER region were identified via linkage to the US Post Office National Change of Address file, follow-up letters, and phone calls. Deaths were ascertained via linkage to the Washington State death file. Statistical Analysis Sex- and multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models that used robust standard errors8 were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for the associations between medication use and risk of hematologic malignancies. Age was the time metric in regression models, with participants entering at the age of completing the baseline questionnaire and exiting at their age at end of follow-up. We selected a priori potential confounders, including known and suspected risk factors, for hematologic malignancies and medical conditions that may be indications for use of NSAIDs for adjustment in multivariable regression models. Specifically, for all models except low-dose aspirin, we adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity (white, Hispanic, other), education (high school graduate or less, some college, college, or advanced degree), smoking (pack-years), self-rated health (excellent, very good, good,fair, poor), history of rheumatoid arthritis, history of nonrheumatoid arthritis or chronic neck/back/joint pain, history of fatigue or lack of energy, history of migraines or frequent headaches, and number of first-degree relatives with a history of leukemia or lymphoma (none, one, two ormore). For low-dose aspirin,which is primarily used for cardiovascular disease prevention rather than pain, we used the same covariates except a history of rheumatoid or nonrheumatoid arthritis or chronic pain but additionally included a history of coronary artery Table 1. Classification of Incident Hematologic Malignancies Disease Patients No. % Myeloid neoplasms 136 23.6 MDS 54 9.4 AML 36 6.2 Myeloproliferative neoplasms 46 8.0 Mature B-cell neoplasms 389 67.4 CLL/SLL 88 15.3 Plasma cell disorders 66 11.4 Other mature B-cell neoplasm entities 235 40.7 Hodgkin’s lymphoma 22 3.8 Mature natural killer/T-cell neoplasms 17 3.0 Others† 13 2.3 Total 577 100 Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL/SLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome. Includes the diagnostic category of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. †Includes cases of malignant lymphoma, not otherwise specified (NOS); leukemia, NOS; acute biphenotypic leukemia; and precursor B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. Analgesics and Incident Hematologic Cancers www.jco.org © 2011 by American Society of Clinical Oncology 2425��