正在加载图片...

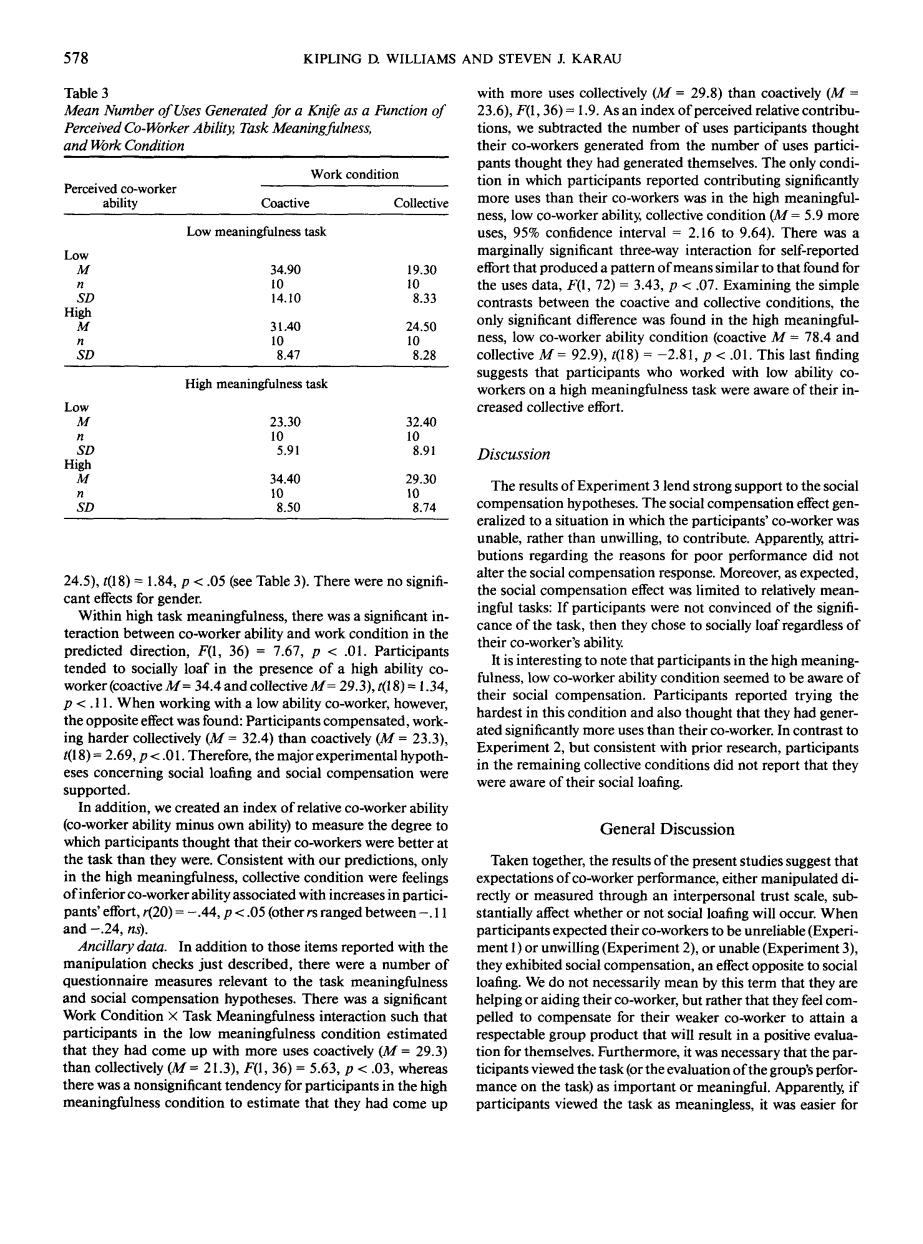

578 KIPLING D.WILLIAMS AND STEVEN J KARAU Table3 and Work Condition their co- mber of uses parti Work condition Coactive Collective more uses than theirc Low meaningfulness task uses.95%confidence interval =2.16 to 9.64).There was a nt three-way intera 34.90 14.10 8.33 the uses data.F(l,72).43,07.Examining the simpl etw and colle 6 ne condition (coa 78.4and 0 is last finding High meaningfulness task creased co ective effor 沿0 5.91 891 Discussion 0 得0 The results of Experiment3 lend strong support to the social "s0 850 8.74 ation cffect gen hich th cial comper 24.5),t(18)=1.84,p<.05 (see Table 3).There were no signifi- the social compensation effect was limited to relatively me teraction bew rke ability and work condition in the PrdicteddirectionnF in the 7.67,p witha lowabil ay co Participant eported trying the a, nthy more uses than their co. ntrast to 受m ively (M 32.4)than coactively (=23.3) dsignifca E supported. were aware of their social loafing. General Discussion o-workers in the high mean rectly sured th ugh an inter nal trust scale sub veen and -.24,ns) ted their n to tho ems reported with the questionnaire measures fing.We do not necessarily mean by this term that they are a signi ingor aiding ther er,bu that they ee estim ctable group product that will result in a positive evalua than collectively.).Fd.36)5.63.03.wh 9. the task sary that the pa pants in the high mance on the t sk)as imp tant or meaningful Apparently if Iness cor they had come up participants viewed the task as meaningless,it was easier for578 KIPLING D. WILLIAMS AND STEVEN J. KARAU Table 3 Mean Number of Uses Generated for a Knife as a Function of Perceived Co-Worker Ability, Task Meaningfulness, and Work Condition Work condition Perceived co-worker ability Coactive Collective Low M n SD High M n SD Low meaningfulness task 34.90 10 14.10 31.40 10 8.47 19.30 10 8.33 24.50 10 8.28 Low M n SD High M n SD High meaningfulness task 23.30 10 5.91 34.40 10 8.50 32.40 10 8.91 29.30 10 8.74 24.5), £(18) = 1.84, p < .05 (see Table 3). There were no significant effects for gender. Within high task meaningfulness, there was a significant interaction between co-worker ability and work condition in the predicted direction, F(l, 36) = 7.67, p < .01. Participants tended to socially loaf in the presence of a high ability coworker (coactive M= 34.4 and collective M= 29.3), t(\ 8) = 1.34, /><.!!. When working with a low ability co-worker, however, the opposite effect was found: Participants compensated, working harder collectively (M = 32.4) than coactively (M = 23.3), t({ 8) = 2.69, p < .01. Therefore, the major experimental hypotheses concerning social loafing and social compensation were supported. In addition, we created an index of relative co-worker ability (co-worker ability minus own ability) to measure the degree to which participants thought that their co-workers were better at the task than they were. Consistent with our predictions, only in the high meaningfulness, collective condition were feelings of inferior co-worker ability associated with increases in participants' effort, r(20) = -.44, p < .05 (other rs ranged between -.11 and —.24, ns). Ancillary data. In addition to those items reported with the manipulation checks just described, there were a number of questionnaire measures relevant to the task meaningfulness and social compensation hypotheses. There was a significant Work Condition X Task Meaningfulness interaction such that participants in the low meaningfulness condition estimated that they had come up with more uses coactively (M = 29.3) than collectively (M= 21.3), F(\, 36) = 5.63, p < .03, whereas there was a nonsignificant tendency for participants in the high meaningfulness condition to estimate that they had come up with more uses collectively (M = 29.8) than coactively (M = 23.6), F(l, 36) = 1.9. As an index of perceived relative contributions, we subtracted the number of uses participants thought their co-workers generated from the number of uses participants thought they had generated themselves. The only condition in which participants reported contributing significantly more uses than their co-workers was in the high meaningfulness, low co-worker ability, collective condition (M= 5.9 more uses, 95% confidence interval = 2.16 to 9.64). There was a marginally significant three-way interaction for self-reported effort that produced a pattern of means similar to that found for the uses data, F(l, 72) = 3.43, p < .07. Examining the simple contrasts between the coactive and collective conditions, the only significant difference was found in the high meaningfulness, low co-worker ability condition (coactive M= 78.4 and collective M= 92.9), t(l&) = -2.81, p < .01. This last finding suggests that participants who worked with low ability coworkers on a high meaningfulness task were aware of their increased collective effort. Discussion The results of Experiment 3 lend strong support to the social compensation hypotheses. The social compensation effect generalized to a situation in which the participants' co-worker was unable, rather than unwilling, to contribute. Apparently, attributions regarding the reasons for poor performance did not alter the social compensation response. Moreover, as expected, the social compensation effect was limited to relatively meaningful tasks: If participants were not convinced of the significance of the task, then they chose to socially loaf regardless of their co-worker's ability. It is interesting to note that participants in the high meaningfulness, low co-worker ability condition seemed to be aware of their social compensation. Participants reported trying the hardest in this condition and also thought that they had generated significantly more uses than their co-worker. In contrast to Experiment 2, but consistent with prior research, participants in the remaining collective conditions did not report that they were aware of their social loafing. General Discussion Taken together, the results of the present studies suggest that expectations of co-worker performance, either manipulated directly or measured through an interpersonal trust scale, substantially affect whether or not social loafing will occur. When participants expected their co-workers to be unreliable (Experiment 1) or unwilling (Experiment 2), or unable (Experiment 3), they exhibited social compensation, an effect opposite to social loafing. We do not necessarily mean by this term that they are helping or aiding their co-worker, but rather that they feel compelled to compensate for their weaker co-worker to attain a respectable group product that will result in a positive evaluation for themselves. Furthermore, it was necessary that the participants viewed the task (or the evaluation of the group's performance on the task) as important or meaningful. Apparently, if participants viewed the task as meaningless, it was easier for