正在加载图片...

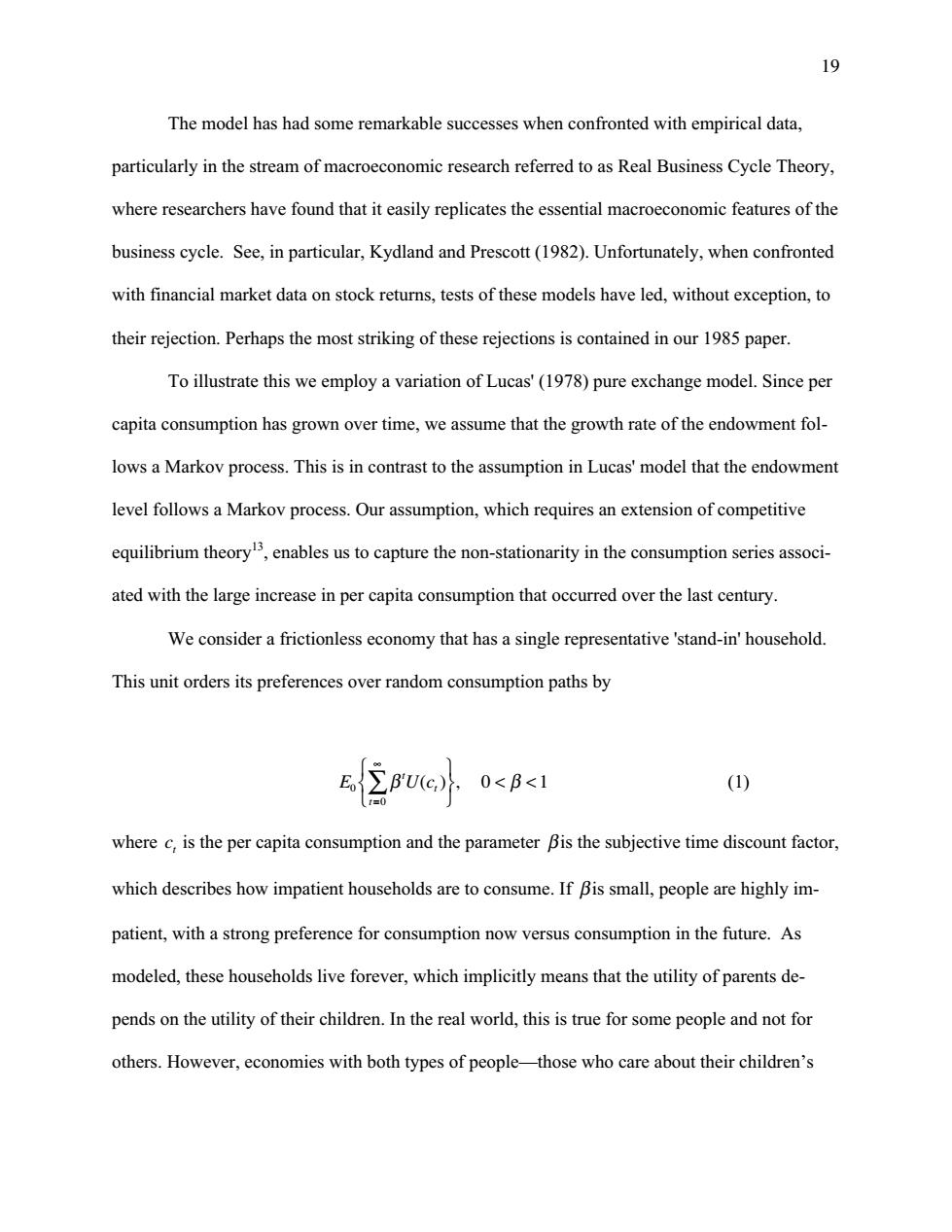

19 The model has had some remarkable successes when confronted with empirical data, particularly in the stream of macroeconomic research referred to as Real Business Cycle Theory, where researchers have found that it easily replicates the essential macroeconomic features of the business cycle.See,in particular,Kydland and Prescott (1982).Unfortunately,when confronted with financial market data on stock returns,tests of these models have led,without exception,to their rejection.Perhaps the most striking of these rejections is contained in our 1985 paper. To illustrate this we employ a variation of Lucas'(1978)pure exchange model.Since per capita consumption has grown over time,we assume that the growth rate of the endowment fol- lows a Markov process.This is in contrast to the assumption in Lucas'model that the endowment level follows a Markov process.Our assumption,which requires an extension of competitive equilibrium theory,enables us to capture the non-stationarity in the consumption series associ- ated with the large increase in per capita consumption that occurred over the last century. We consider a frictionless economy that has a single representative 'stand-in'household. This unit orders its preferences over random consumption paths by 0<B<1 (1) where c,is the per capita consumption and the parameter Bis the subjective time discount factor, which describes how impatient households are to consume.If Bis small,people are highly im- patient,with a strong preference for consumption now versus consumption in the future.As modeled,these households live forever,which implicitly means that the utility of parents de- pends on the utility of their children.In the real world,this is true for some people and not for others.However,economies with both types of people-those who care about their children's19 The model has had some remarkable successes when confronted with empirical data, particularly in the stream of macroeconomic research referred to as Real Business Cycle Theory, where researchers have found that it easily replicates the essential macroeconomic features of the business cycle. See, in particular, Kydland and Prescott (1982). Unfortunately, when confronted with financial market data on stock returns, tests of these models have led, without exception, to their rejection. Perhaps the most striking of these rejections is contained in our 1985 paper. To illustrate this we employ a variation of Lucas' (1978) pure exchange model. Since per capita consumption has grown over time, we assume that the growth rate of the endowment follows a Markov process. This is in contrast to the assumption in Lucas' model that the endowment level follows a Markov process. Our assumption, which requires an extension of competitive equilibrium theory13, enables us to capture the non-stationarity in the consumption series associated with the large increase in per capita consumption that occurred over the last century. We consider a frictionless economy that has a single representative 'stand-in' household. This unit orders its preferences over random consumption paths by E Uc t t 0 t 0 b b 0 1 = • Â Ï Ì Ó ¸ ˝ ˛ ( ) , < < (1) where ct is the per capita consumption and the parameter bis the subjective time discount factor, which describes how impatient households are to consume. If bis small, people are highly impatient, with a strong preference for consumption now versus consumption in the future. As modeled, these households live forever, which implicitly means that the utility of parents depends on the utility of their children. In the real world, this is true for some people and not for others. However, economies with both types of people—those who care about their children’s