正在加载图片...

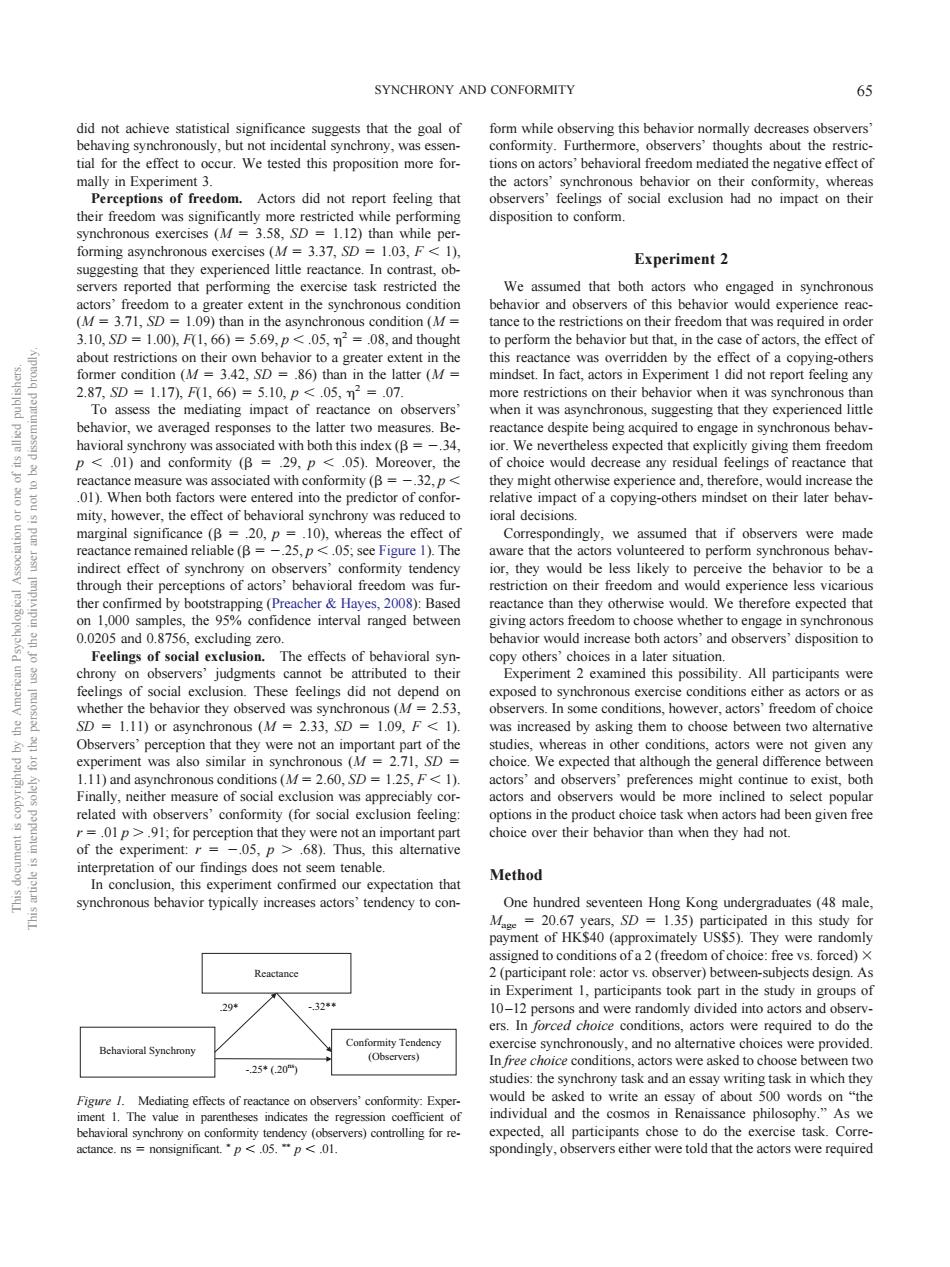

SYNCHRONY AND CONFORMITY for the effeet to ur.We tested this propsition more for- onsonaciorsbehaviorlficedommcdiaicdihenegatiecfectol he actors Actors did n Experiment 2 d the extent in the s ence reac edinord was overridden by the g an freed 01)and 29、D .05).Mor choice would decre se any residual fee ings c 25,p05;sce Figure 1).The d that if ered to sh their nfimed by b nce than they othe wise would.We therefore expected that weer Feelings of social exclusion The behv rtic of social on Thes e feelings did not de d nchronous exercise conditi s either as actors or as (M 2.33 ns,F ever actors'free ers n that the not an whereas in other h lusion ppreciably cor would b p>.9Lo een given fre of the 68 In conelus Method synchronous behavior typically increases actors'tendency to con- tely USS5).They were random imen.participants took part in the study in groups of 25*2 igure Mediating effects of reactance on observers'conform words or d s the regr ected.all p lline for m participants chose to do the did not achieve statistical significance suggests that the goal of behaving synchronously, but not incidental synchrony, was essential for the effect to occur. We tested this proposition more formally in Experiment 3. Perceptions of freedom. Actors did not report feeling that their freedom was significantly more restricted while performing synchronous exercises (M 3.58, SD 1.12) than while performing asynchronous exercises (M 3.37, SD 1.03, F 1), suggesting that they experienced little reactance. In contrast, observers reported that performing the exercise task restricted the actors’ freedom to a greater extent in the synchronous condition (M 3.71, SD 1.09) than in the asynchronous condition (M 3.10, SD 1.00), F(1, 66) 5.69, p .05, 2 .08, and thought about restrictions on their own behavior to a greater extent in the former condition (M 3.42, SD .86) than in the latter (M 2.87, SD 1.17), F(1, 66) 5.10, p .05, 2 .07. To assess the mediating impact of reactance on observers’ behavior, we averaged responses to the latter two measures. Behavioral synchrony was associated with both this index (.34, p .01) and conformity ( .29, p .05). Moreover, the reactance measure was associated with conformity (.32, p .01). When both factors were entered into the predictor of conformity, however, the effect of behavioral synchrony was reduced to marginal significance ( .20, p .10), whereas the effect of reactance remained reliable (.25, p .05; see Figure 1). The indirect effect of synchrony on observers’ conformity tendency through their perceptions of actors’ behavioral freedom was further confirmed by bootstrapping (Preacher & Hayes, 2008): Based on 1,000 samples, the 95% confidence interval ranged between 0.0205 and 0.8756, excluding zero. Feelings of social exclusion. The effects of behavioral synchrony on observers’ judgments cannot be attributed to their feelings of social exclusion. These feelings did not depend on whether the behavior they observed was synchronous (M 2.53, SD 1.11) or asynchronous (M 2.33, SD 1.09, F 1). Observers’ perception that they were not an important part of the experiment was also similar in synchronous (M 2.71, SD 1.11) and asynchronous conditions (M 2.60, SD 1.25, F 1). Finally, neither measure of social exclusion was appreciably correlated with observers’ conformity (for social exclusion feeling: r .01 p .91; for perception that they were not an important part of the experiment: r .05, p .68). Thus, this alternative interpretation of our findings does not seem tenable. In conclusion, this experiment confirmed our expectation that synchronous behavior typically increases actors’ tendency to conform while observing this behavior normally decreases observers’ conformity. Furthermore, observers’ thoughts about the restrictions on actors’ behavioral freedom mediated the negative effect of the actors’ synchronous behavior on their conformity, whereas observers’ feelings of social exclusion had no impact on their disposition to conform. Experiment 2 We assumed that both actors who engaged in synchronous behavior and observers of this behavior would experience reactance to the restrictions on their freedom that was required in order to perform the behavior but that, in the case of actors, the effect of this reactance was overridden by the effect of a copying-others mindset. In fact, actors in Experiment 1 did not report feeling any more restrictions on their behavior when it was synchronous than when it was asynchronous, suggesting that they experienced little reactance despite being acquired to engage in synchronous behavior. We nevertheless expected that explicitly giving them freedom of choice would decrease any residual feelings of reactance that they might otherwise experience and, therefore, would increase the relative impact of a copying-others mindset on their later behavioral decisions. Correspondingly, we assumed that if observers were made aware that the actors volunteered to perform synchronous behavior, they would be less likely to perceive the behavior to be a restriction on their freedom and would experience less vicarious reactance than they otherwise would. We therefore expected that giving actors freedom to choose whether to engage in synchronous behavior would increase both actors’ and observers’ disposition to copy others’ choices in a later situation. Experiment 2 examined this possibility. All participants were exposed to synchronous exercise conditions either as actors or as observers. In some conditions, however, actors’ freedom of choice was increased by asking them to choose between two alternative studies, whereas in other conditions, actors were not given any choice. We expected that although the general difference between actors’ and observers’ preferences might continue to exist, both actors and observers would be more inclined to select popular options in the product choice task when actors had been given free choice over their behavior than when they had not. Method One hundred seventeen Hong Kong undergraduates (48 male, Mage 20.67 years, SD 1.35) participated in this study for payment of HK$40 (approximately US$5). They were randomly assigned to conditions of a 2 (freedom of choice: free vs. forced) 2 (participant role: actor vs. observer) between-subjects design. As in Experiment 1, participants took part in the study in groups of 10 –12 persons and were randomly divided into actors and observers. In forced choice conditions, actors were required to do the exercise synchronously, and no alternative choices were provided. In free choice conditions, actors were asked to choose between two studies: the synchrony task and an essay writing task in which they would be asked to write an essay of about 500 words on “the individual and the cosmos in Renaissance philosophy.” As we expected, all participants chose to do the exercise task. Correspondingly, observers either were told that the actors were required Behavioral Synchrony Reactance Conformity Tendency (Observers) .29* -.32** -.25* (.20ns) Figure 1. Mediating effects of reactance on observers’ conformity: Experiment 1. The value in parentheses indicates the regression coefficient of behavioral synchrony on conformity tendency (observers) controlling for reactance. ns nonsignificant. p .05. p .01. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. SYNCHRONY AND CONFORMITY 65���������������������������������������