正在加载图片...

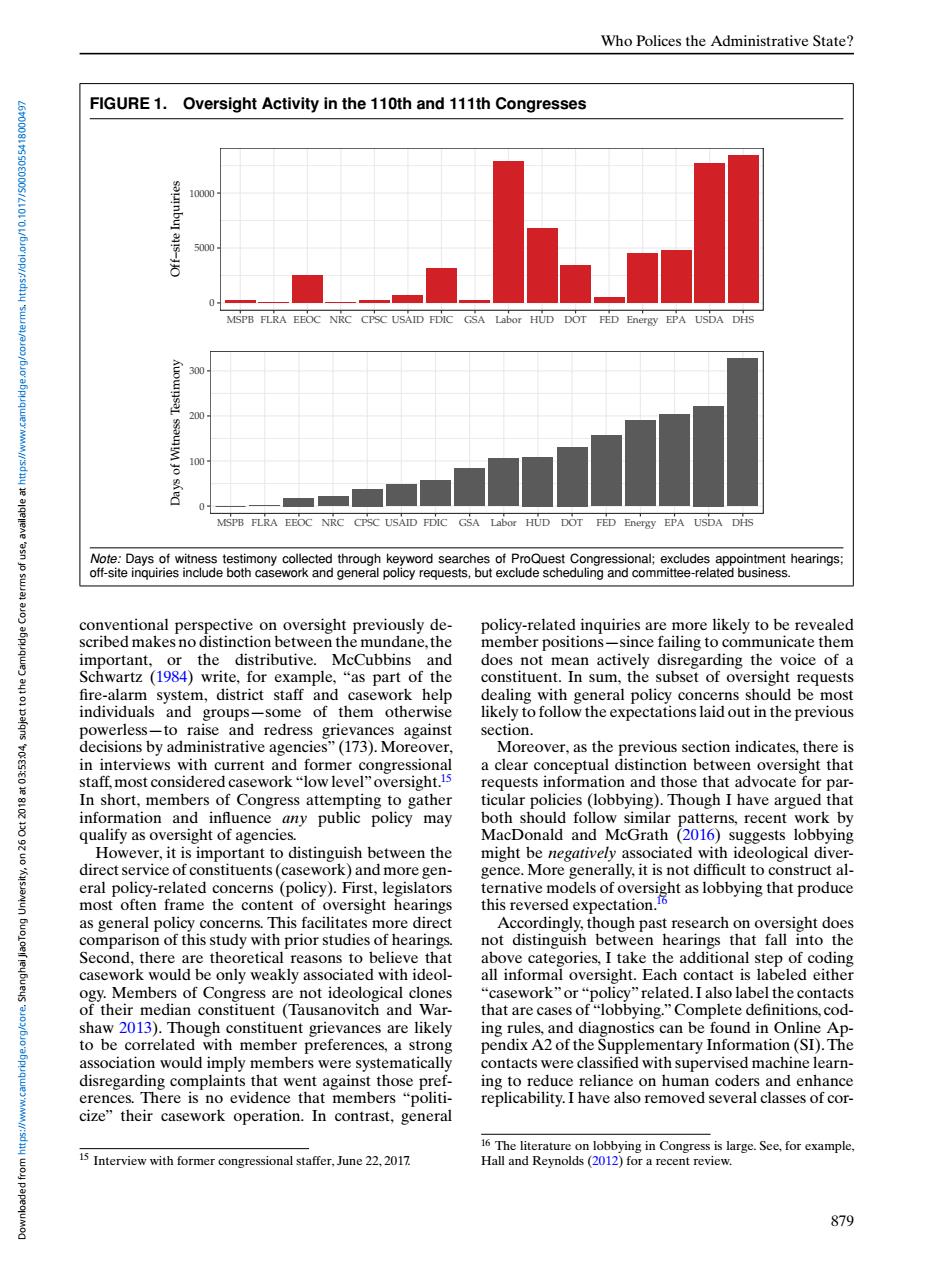

Who Polices the Administrative State? FIGURE 1.Oversight Activity in the 110th and 111th Congresses 10000 5000 MSPB FLRA EEOC NRC CPSC USAID FDIC GSA Labor HUD DOT FED Energy EPA USDA DHS 300 200 00 4号 MSPB FLRA EEOC NRC CPSC USAID FDIC GSA Labor HUD DOT FED Energy EPA USDA DHS Note:Days of witness testimony collected through keyword searches of ProQuest Congressional;excludes appointment hearings; off-site inquiries include both casework and general policy requests,but exclude scheduling and committee-related business. conventional perspective on oversight previously de- policy-related inquiries are more likely to be revealed scribed makes no distinction between the mundane,the member positions-since failing to communicate them important,or the distributive.McCubbins and does not mean actively disregarding the voice of a Schwartz (1984)write,for example,"as part of the constituent.In sum,the subset of oversight requests fire-alarm system,district staff and casework help dealing with general policy concerns should be most individuals and groups-some of them otherwise likely to follow the expectations laid out in the previous powerless-to raise and redress grievances against section. decisions by administrative agencies"(173).Moreover, Moreover,as the previous section indicates,there is in interviews with current and former congressional a clear conceptual distinction between oversight that staff,most considered casework"low level"oversight.15 requests information and those that advocate for par- In short,members of Congress attempting to gather ticular policies (lobbying).Though I have argued that information and influence any public policy may both should follow similar patterns,recent work by qualify as oversight of agencies. MacDonald and McGrath (2016)suggests lobbying However,it is important to distinguish between the might be negatively associated with ideological diver- direct service of constituents(casework)and more gen- gence.More generally,it is not difficult to construct al- eral policy-related concerns (policy).First,legislators ternative models of oversight as lobbying that produce most often frame the content of oversight hearings this reversed expectation. as general policy concerns.This facilitates more direct Accordingly,though past research on oversight does comparison of this study with prior studies of hearings not distinguish between hearings that fall into the Second,there are theoretical reasons to believe that above categories,I take the additional step of coding casework would be only weakly associated with ideol- all informal oversight.Each contact is labeled either ogy.Members of Congress are not ideological clones "casework"or"policy"related.I also label the contacts of their median constituent (Tausanovitch and War- that are cases of"lobbying."Complete definitions,cod- shaw 2013).Though constituent grievances are likely ing rules,and diagnostics can be found in Online Ap- to be correlated with member preferences,a strong pendix A2 of the Supplementary Information(SI).The association would imply members were systematically contacts were classified with supervised machine learn- disregarding complaints that went against those pref- ing to reduce reliance on human coders and enhance erences.There is no evidence that members "politi- replicability.I have also removed several classes of cor- cize"their casework operation.In contrast,general 16 The literature on lobbying in Congress is large.See,for example, 15 Interview with former congressional staffer,June 22,2017 Hall and Reynolds(2012)for a recent review. 879Who Polices the Administrative State? FIGURE 1. Oversight Activity in the 110th and 111th Congresses 0 5000 10000 MSPB FLRA EEOC NRC CPSC USAID FDIC GSA Labor HUD DOT FED Energy EPA USDA DHS Off−site Inquiries 0 100 200 300 MSPB FLRA EEOC NRC CPSC USAID FDIC GSA Labor HUD DOT FED Energy EPA USDA DHS Days of Witness Testimony Note: Days of witness testimony collected through keyword searches of ProQuest Congressional; excludes appointment hearings; off-site inquiries include both casework and general policy requests, but exclude scheduling and committee-related business. conventional perspective on oversight previously described makes no distinction between the mundane, the important, or the distributive. McCubbins and Schwartz (1984) write, for example, “as part of the fire-alarm system, district staff and casework help individuals and groups—some of them otherwise powerless—to raise and redress grievances against decisions by administrative agencies” (173). Moreover, in interviews with current and former congressional staff,most considered casework “low level” oversight.15 In short, members of Congress attempting to gather information and influence any public policy may qualify as oversight of agencies. However, it is important to distinguish between the direct service of constituents (casework) and more general policy-related concerns (policy). First, legislators most often frame the content of oversight hearings as general policy concerns. This facilitates more direct comparison of this study with prior studies of hearings. Second, there are theoretical reasons to believe that casework would be only weakly associated with ideology. Members of Congress are not ideological clones of their median constituent (Tausanovitch and Warshaw 2013). Though constituent grievances are likely to be correlated with member preferences, a strong association would imply members were systematically disregarding complaints that went against those preferences. There is no evidence that members “politicize” their casework operation. In contrast, general 15 Interview with former congressional staffer, June 22, 2017. policy-related inquiries are more likely to be revealed member positions—since failing to communicate them does not mean actively disregarding the voice of a constituent. In sum, the subset of oversight requests dealing with general policy concerns should be most likely to follow the expectations laid out in the previous section. Moreover, as the previous section indicates, there is a clear conceptual distinction between oversight that requests information and those that advocate for particular policies (lobbying). Though I have argued that both should follow similar patterns, recent work by MacDonald and McGrath (2016) suggests lobbying might be negatively associated with ideological divergence. More generally, it is not difficult to construct alternative models of oversight as lobbying that produce this reversed expectation.16 Accordingly, though past research on oversight does not distinguish between hearings that fall into the above categories, I take the additional step of coding all informal oversight. Each contact is labeled either “casework” or “policy” related. I also label the contacts that are cases of “lobbying.” Complete definitions, coding rules, and diagnostics can be found in Online Appendix A2 of the Supplementary Information (SI). The contacts were classified with supervised machine learning to reduce reliance on human coders and enhance replicability. I have also removed several classes of cor- 16 The literature on lobbying in Congress is large. See, for example, Hall and Reynolds (2012) for a recent review. 879 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Shanghai JiaoTong University, on 26 Oct 2018 at 03:53:04, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000497