正在加载图片...

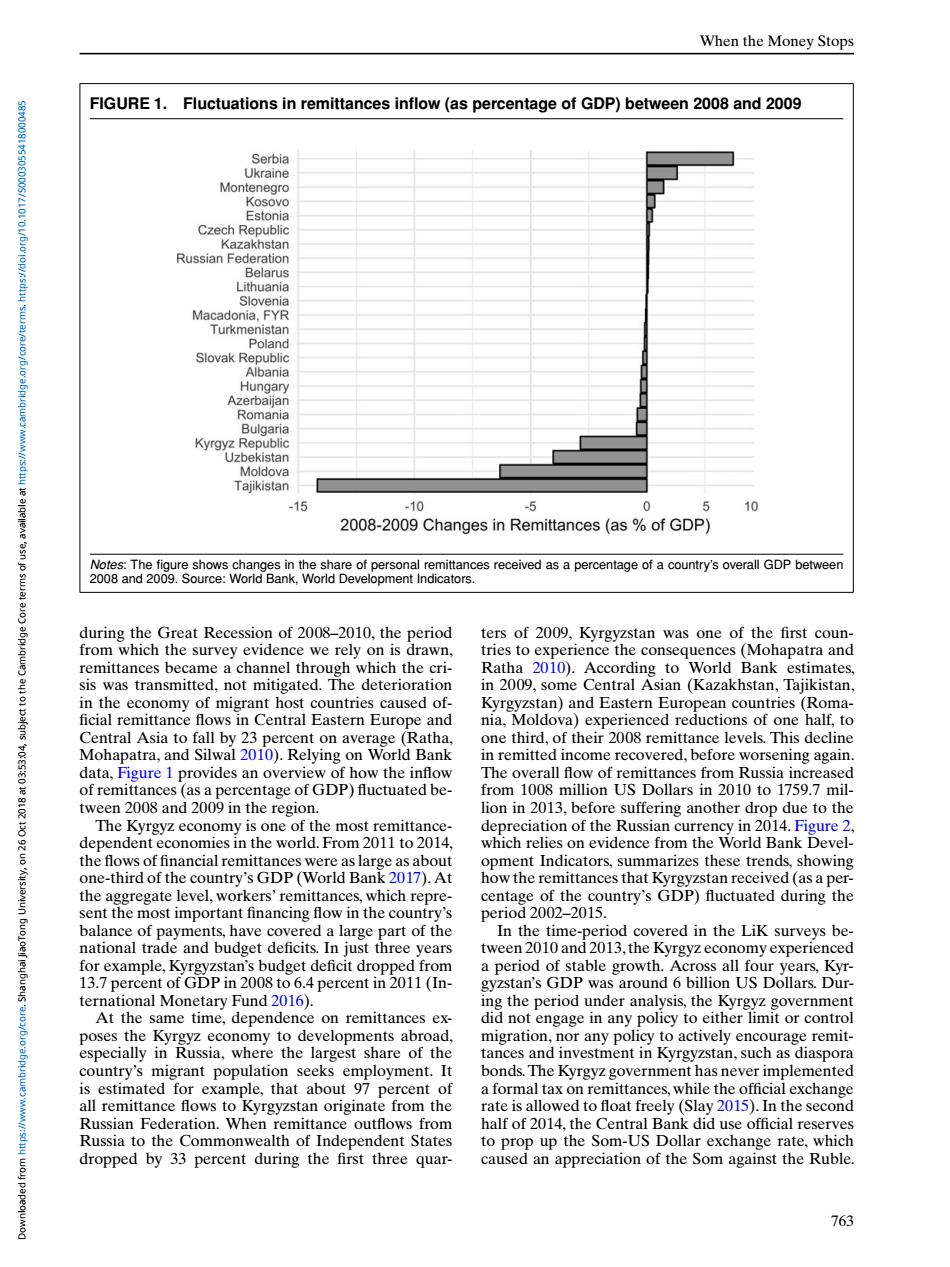

When the Money Stops FIGURE 1.Fluctuations in remittances inflow(as percentage of GDP)between 2008 and 2009 Serbia Ukraine Montenegro Kosovo Estonia Czech Republic Kazakhstan Russian Federation Belarus Lithuania Slovenia Macadonia,FYR Turkmenistan Poland Slovak Republic Albania Hungary Azerbaijan Romania Bulgaria Kyrgyz Republic Uzbekistan Moldova Tajikistan 4号 -15 -10 0 5 10 2008-2009 Changes in Remittances(as of GDP) Notes:The figure shows changes in the share of personal remittances received as a percentage of a country's overall GDP between 2008 and 2009.Source:World Bank,World Development Indicators. during the Great Recession of 2008-2010,the period ters of 2009,Kyrgyzstan was one of the first coun- from which the survey evidence we rely on is drawn tries to experience the consequences (Mohapatra and remittances became a channel through which the cri- Ratha 2010).According to World Bank estimates, 是 sis was transmitted,not mitigated.The deterioration in 2009,some Central Asian (Kazakhstan,Tajikistan, in the economy of migrant host countries caused of- Kyrgyzstan)and Eastern European countries(Roma- ficial remittance flows in Central Eastern Europe and nia,Moldova)experienced reductions of one half,to Central Asia to fall by 23 percent on average (Ratha, one third,of their 2008 remittance levels.This decline Mohapatra,and Silwal 2010).Relying on World Bank in remitted income recovered,before worsening again. data,Figure 1 provides an overview of how the inflow The overall flow of remittances from Russia increased of remittances(as a percentage of GDP)fluctuated be- from 1008 million US Dollars in 2010 to 1759.7 mil- tween 2008 and 2009 in the region. lion in 2013,before suffering another drop due to the The Kyrgyz economy is one of the most remittance- depreciation of the Russian currency in 2014.Figure 2, dependent economies in the world.From 2011 to 2014, which relies on evidence from the World Bank Devel- the flows of financial remittances were as large as about opment Indicators,summarizes these trends,showing one-third of the country's GDP (World Bank 2017).At how the remittances that Kyrgyzstan received(as a per- the aggregate level,workers'remittances,which repre- centage of the country's GDP)fluctuated during the sent the most important financing flow in the country's period2002-2015. balance of payments,have covered a large part of the In the time-period covered in the LiK surveys be- national trade and budget deficits.In just three years tween 2010 and 2013,the Kyrgyz economy experienced for example,Kyrgyzstan's budget deficit dropped from a period of stable growth.Across all four years,Kyr- eys 13.7 percent of GDP in 2008 to 6.4 percent in 2011(In- gyzstan's GDP was around 6 billion US Dollars.Dur- ternational Monetary Fund 2016). ing the period under analysis,the Kyrgyz government At the same time,dependence on remittances ex- did not engage in any policy to either limit or control poses the Kyrgyz economy to developments abroad. migration,nor any policy to actively encourage remit- especially in Russia,where the largest share of the tances and investment in Kyrgyzstan,such as diaspora country's migrant population seeks employment.It bonds.The Kyrgyz government has never implemented is estimated for example,that about 97 percent of a formal tax on remittances,while the official exchange all remittance flows to Kyrgyzstan originate from the rate is allowed to float freely (Slay 2015).In the second Russian Federation.When remittance outflows from half of 2014.the Central Bank did use official reserves Russia to the Commonwealth of Independent States to prop up the Som-US Dollar exchange rate,which dropped by 33 percent during the first three quar- caused an appreciation of the Som against the Ruble. 763When the Money Stops FIGURE 1. Fluctuations in remittances inflow (as percentage of GDP) between 2008 and 2009 Notes: The figure shows changes in the share of personal remittances received as a percentage of a country’s overall GDP between 2008 and 2009. Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators. during the Great Recession of 2008–2010, the period from which the survey evidence we rely on is drawn, remittances became a channel through which the crisis was transmitted, not mitigated. The deterioration in the economy of migrant host countries caused official remittance flows in Central Eastern Europe and Central Asia to fall by 23 percent on average (Ratha, Mohapatra, and Silwal 2010). Relying on World Bank data, Figure 1 provides an overview of how the inflow of remittances (as a percentage of GDP) fluctuated between 2008 and 2009 in the region. The Kyrgyz economy is one of the most remittancedependent economies in the world. From 2011 to 2014, the flows of financial remittances were as large as about one-third of the country’s GDP (World Bank 2017). At the aggregate level, workers’ remittances, which represent the most important financing flow in the country’s balance of payments, have covered a large part of the national trade and budget deficits. In just three years for example, Kyrgyzstan’s budget deficit dropped from 13.7 percent of GDP in 2008 to 6.4 percent in 2011 (International Monetary Fund 2016). At the same time, dependence on remittances exposes the Kyrgyz economy to developments abroad, especially in Russia, where the largest share of the country’s migrant population seeks employment. It is estimated for example, that about 97 percent of all remittance flows to Kyrgyzstan originate from the Russian Federation. When remittance outflows from Russia to the Commonwealth of Independent States dropped by 33 percent during the first three quarters of 2009, Kyrgyzstan was one of the first countries to experience the consequences (Mohapatra and Ratha 2010). According to World Bank estimates, in 2009, some Central Asian (Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan) and Eastern European countries (Romania, Moldova) experienced reductions of one half, to one third, of their 2008 remittance levels. This decline in remitted income recovered, before worsening again. The overall flow of remittances from Russia increased from 1008 million US Dollars in 2010 to 1759.7 million in 2013, before suffering another drop due to the depreciation of the Russian currency in 2014. Figure 2, which relies on evidence from the World Bank Development Indicators, summarizes these trends, showing how the remittances that Kyrgyzstan received (as a percentage of the country’s GDP) fluctuated during the period 2002–2015. In the time-period covered in the LiK surveys between 2010 and 2013, the Kyrgyz economy experienced a period of stable growth. Across all four years, Kyrgyzstan’s GDP was around 6 billion US Dollars. During the period under analysis, the Kyrgyz government did not engage in any policy to either limit or control migration, nor any policy to actively encourage remittances and investment in Kyrgyzstan, such as diaspora bonds.The Kyrgyz government has never implemented a formal tax on remittances, while the official exchange rate is allowed to float freely (Slay 2015). In the second half of 2014, the Central Bank did use official reserves to prop up the Som-US Dollar exchange rate, which caused an appreciation of the Som against the Ruble. 763 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Shanghai JiaoTong University, on 26 Oct 2018 at 03:53:04, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000485