正在加载图片...

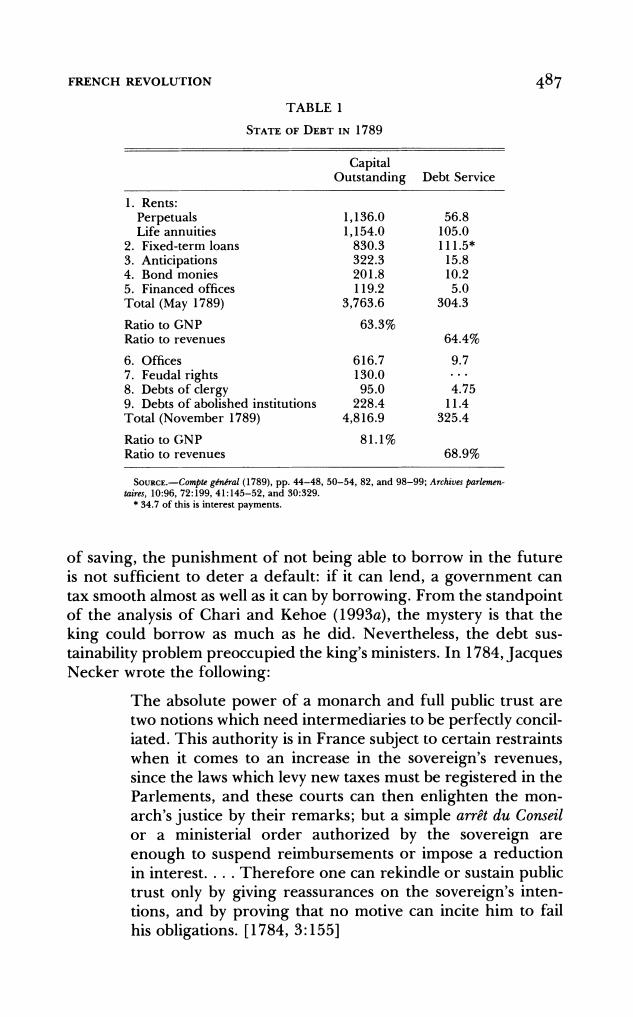

FRENCH REVOLUTION 487 TABLE 1 STATE OF DEBT IN 1789 Capital Outstanding Debt Service 1.Rents: Perpetuals 1,136.0 56.8 Life annuities 1,154.0 105.0 2.Fixed-term loans 830.3 111.5* 3.Anticipations 322.3 15.8 4.Bond monies 201.8 10.2 5.Financed offices 119.2 5.0 Total (May 1789) 3,763.6 304.3 Ratio to GNP 63.3% Ratio to revenues 64.4% 6.Offices 616.7 9.7 7.Feudal rights 130.0 。。。 8.Debts of clergy 95.0 4.75 9.Debts of abolished institutions 228.4 11.4 Total (November 1789) 4,816.9 325.4 Ratio to GNP 81.1% Ratio to revenues 68.9% SoURCE.-Compte general (1789),pp.44-48,50-54,82,and 98-99:Archives parlemen- ai5,10:96,72:i99,41:l45-52,and30:329. *34.7 of this is interest payments. of saving,the punishment of not being able to borrow in the future is not sufficient to deter a default:if it can lend,a government can tax smooth almost as well as it can by borrowing.From the standpoint of the analysis of Chari and Kehoe(1993a),the mystery is that the king could borrow as much as he did.Nevertheless,the debt sus- tainability problem preoccupied the king's ministers.In 1784,Jacques Necker wrote the following: The absolute power of a monarch and full public trust are two notions which need intermediaries to be perfectly concil- iated.This authority is in France subject to certain restraints when it comes to an increase in the sovereign's revenues, since the laws which levy new taxes must be registered in the Parlements,and these courts can then enlighten the mon- arch's justice by their remarks;but a simple arret du Conseil or a ministerial order authorized by the sovereign are enough to suspend reimbursements or impose a reduction in interest....Therefore one can rekindle or sustain public trust only by giving reassurances on the sovereign's inten- tions,and by proving that no motive can incite him to fail his obligations.[1784,3:155]FRENCH REVOLUTION 487 TABLE 1 STATE OF DEBT IN 1789 Capital Outstanding Debt Service 1. Rents: Perpetuals 1,136.0 56.8 Life annuities 1,154.0 105.0 2. Fixed-term loans 830.3 111.5* 3. Anticipations 322.3 15.8 4. Bond monies 201.8 10.2 5. Financed offices 119.2 5.0 Total (May 1789) 3,763.6 304.3 Ratio to GNP 63.3% Ratio to revenues 64.4% 6. Offices 616.7 9.7 7. Feudal rights 130.0 ... 8. Debts of clergy 95.0 4.75 9. Debts of abolished institutions 228.4 11.4 Total (November 1789) 4,816.9 325.4 Ratio to GNP 81.1% Ratio to revenues 68.9% SOURCE.-Compte gbdral (1789), pp. 44-48, 50-54, 82, and 98-99; Archives parlementaires, 10:96, 72:199, 41:145-52, and 30:329. * 34.7 of this is interest payments. of saving, the punishment of not being able to borrow in the future is not sufficient to deter a default: if it can lend, a government can tax smooth almost as well as it can by borrowing. From the standpoint of the analysis of Chari and Kehoe (1993a), the mystery is that the king could borrow as much as he did. Nevertheless, the debt sustainability problem preoccupied the king's ministers. In 1784, Jacques Necker wrote the following: The absolute power of a monarch and full public trust are two notions which need intermediaries to be perfectly conciliated. This authority is in France subject to certain restraints when it comes to an increase in the sovereign's revenues, since the laws which levy new taxes must be registered in the Parlements, and these courts can then enlighten the monarch's justice by their remarks; but a simple arr&t du Conseil or a ministerial order authorized by the sovereign are enough to suspend reimbursements or impose a reduction in interest.... Therefore one can rekindle or sustain public trust only by giving reassurances on the sovereign's intentions, and by proving that no motive can incite him to fail his obligations. [1784, 3:155]