正在加载图片...

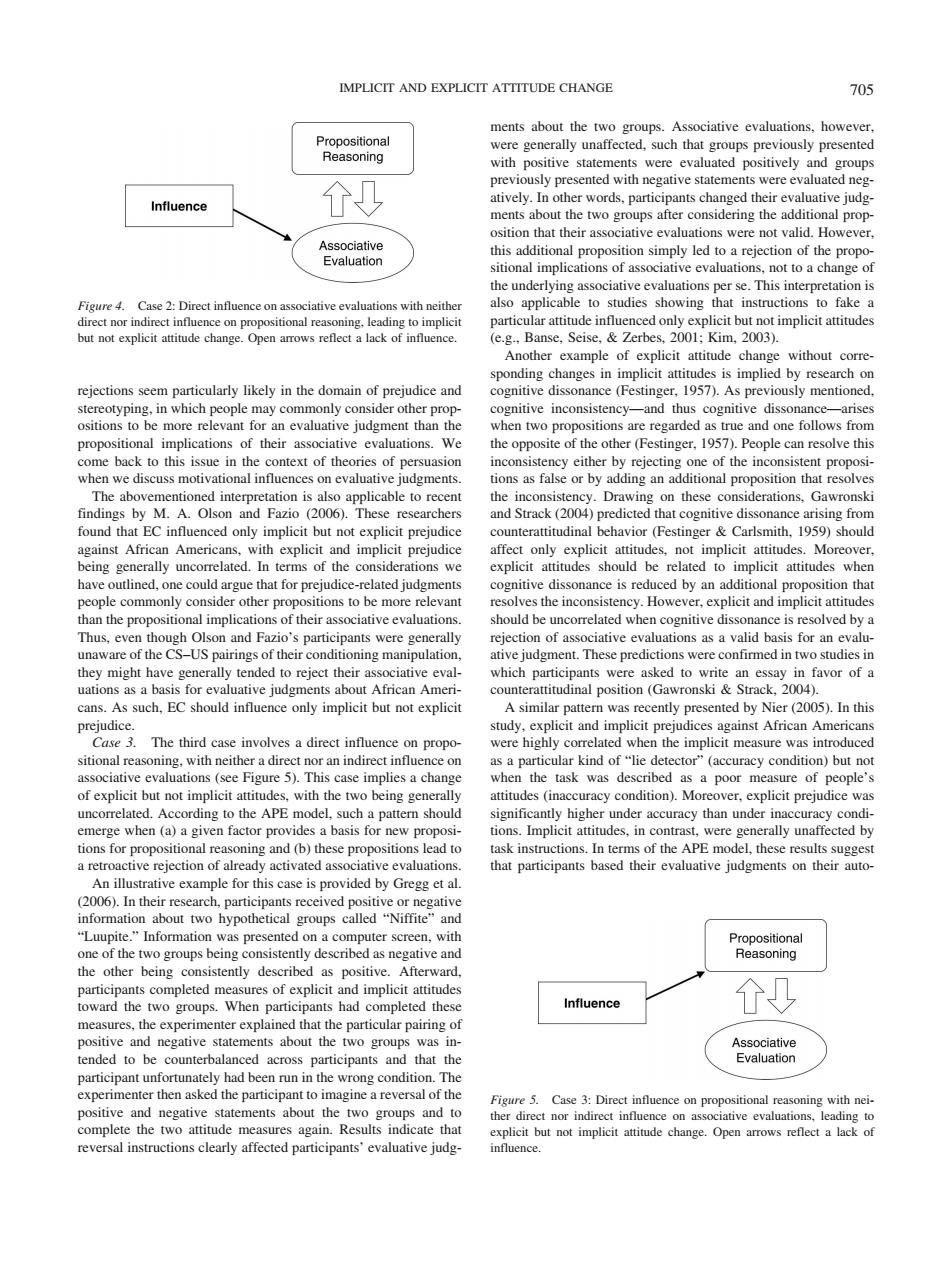

IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDE CHANGE 105 Ppeonog wh positiv staten Influence osition simply led to a rejection of the prop not to a change with to fake nothe xample of explicit attitude change without corre eiections seem particularly likely in the domain of prejudice and implications of their associative evaluations. the op back to this issue in the tent propos he a ion is als Dra wing on these co ed on atfectonlycplictatiutg implicit attitud itive diss ance is red e vesthe inconsisteney.However.explicit and Thus,even thoughson and Fazio's participants were n of as ative evalu sas a valid bas alu of the S pairingso on ning m s as a basis for evalu n (Ga 2004 As such,ECs动 influence only implicit but not explic it and The third case involves a direct influence on propo when the task was de da poor me with the two being generally ).M ver.explicit prejudice wa emerge when (a)a given factor pr des a basis for new Implicit attitudes.in c tra vere generally unaffected b soning d (b) Information was presente the other beins consistently described as r itive Influence 个0 the explained that the particular pairi tive about the two group to be artici n.The and to ning with nci ative complete the two attitud mea sures again.Resul e.Ope reversal instructions clearly affected participants'e ive judg rejections seem particularly likely in the domain of prejudice and stereotyping, in which people may commonly consider other propositions to be more relevant for an evaluative judgment than the propositional implications of their associative evaluations. We come back to this issue in the context of theories of persuasion when we discuss motivational influences on evaluative judgments. The abovementioned interpretation is also applicable to recent findings by M. A. Olson and Fazio (2006). These researchers found that EC influenced only implicit but not explicit prejudice against African Americans, with explicit and implicit prejudice being generally uncorrelated. In terms of the considerations we have outlined, one could argue that for prejudice-related judgments people commonly consider other propositions to be more relevant than the propositional implications of their associative evaluations. Thus, even though Olson and Fazio’s participants were generally unaware of the CS–US pairings of their conditioning manipulation, they might have generally tended to reject their associative evaluations as a basis for evaluative judgments about African Americans. As such, EC should influence only implicit but not explicit prejudice. Case 3. The third case involves a direct influence on propositional reasoning, with neither a direct nor an indirect influence on associative evaluations (see Figure 5). This case implies a change of explicit but not implicit attitudes, with the two being generally uncorrelated. According to the APE model, such a pattern should emerge when (a) a given factor provides a basis for new propositions for propositional reasoning and (b) these propositions lead to a retroactive rejection of already activated associative evaluations. An illustrative example for this case is provided by Gregg et al. (2006). In their research, participants received positive or negative information about two hypothetical groups called “Niffite” and “Luupite.” Information was presented on a computer screen, with one of the two groups being consistently described as negative and the other being consistently described as positive. Afterward, participants completed measures of explicit and implicit attitudes toward the two groups. When participants had completed these measures, the experimenter explained that the particular pairing of positive and negative statements about the two groups was intended to be counterbalanced across participants and that the participant unfortunately had been run in the wrong condition. The experimenter then asked the participant to imagine a reversal of the positive and negative statements about the two groups and to complete the two attitude measures again. Results indicate that reversal instructions clearly affected participants’ evaluative judgments about the two groups. Associative evaluations, however, were generally unaffected, such that groups previously presented with positive statements were evaluated positively and groups previously presented with negative statements were evaluated negatively. In other words, participants changed their evaluative judgments about the two groups after considering the additional proposition that their associative evaluations were not valid. However, this additional proposition simply led to a rejection of the propositional implications of associative evaluations, not to a change of the underlying associative evaluations per se. This interpretation is also applicable to studies showing that instructions to fake a particular attitude influenced only explicit but not implicit attitudes (e.g., Banse, Seise, & Zerbes, 2001; Kim, 2003). Another example of explicit attitude change without corresponding changes in implicit attitudes is implied by research on cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957). As previously mentioned, cognitive inconsistency—and thus cognitive dissonance—arises when two propositions are regarded as true and one follows from the opposite of the other (Festinger, 1957). People can resolve this inconsistency either by rejecting one of the inconsistent propositions as false or by adding an additional proposition that resolves the inconsistency. Drawing on these considerations, Gawronski and Strack (2004) predicted that cognitive dissonance arising from counterattitudinal behavior (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959) should affect only explicit attitudes, not implicit attitudes. Moreover, explicit attitudes should be related to implicit attitudes when cognitive dissonance is reduced by an additional proposition that resolves the inconsistency. However, explicit and implicit attitudes should be uncorrelated when cognitive dissonance is resolved by a rejection of associative evaluations as a valid basis for an evaluative judgment. These predictions were confirmed in two studies in which participants were asked to write an essay in favor of a counterattitudinal position (Gawronski & Strack, 2004). A similar pattern was recently presented by Nier (2005). In this study, explicit and implicit prejudices against African Americans were highly correlated when the implicit measure was introduced as a particular kind of “lie detector” (accuracy condition) but not when the task was described as a poor measure of people’s attitudes (inaccuracy condition). Moreover, explicit prejudice was significantly higher under accuracy than under inaccuracy conditions. Implicit attitudes, in contrast, were generally unaffected by task instructions. In terms of the APE model, these results suggest that participants based their evaluative judgments on their autoFigure 4. Case 2: Direct influence on associative evaluations with neither direct nor indirect influence on propositional reasoning, leading to implicit but not explicit attitude change. Open arrows reflect a lack of influence. Figure 5. Case 3: Direct influence on propositional reasoning with neither direct nor indirect influence on associative evaluations, leading to explicit but not implicit attitude change. Open arrows reflect a lack of influence. IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT ATTITUDE CHANGE 705