Why Do We Need the Liberal Arts?Because It Gives Us Sci-fi JUDITH SHULEVITZ The liberal arts are very old and very distinguished,and those who teach them are among the bitterest people I know.University presidents,trustees,and state legislatures are slashing their funding or getting rid of their subjects altogether. (French,German,Italian,and the classics will likely be the first to go.)Governor Rick Scott of Florida thinks that state universities should charge higher tuition to students who choose majors in fields that don't lead directly to jobs.Even the social sciences are endangered:Republicans in Congress have been trying to pass an amendment to an appropriations bill that would forbid the National Science Foundation from funding any research in the human sciences not considered essential for America's security or economic interests.Meanwhile,in their pristine new laboratories,the natural sciences thrive."Spending for the humanities research in 2011 amounted to less than half of one percent of the amount dedicated to science and engineering research and development in the United States,"English professor Homi Bhabha said at a gloomy conference on the future of the humanities at Harvard in April,2013. umes Illustration by Joe Wilson How does one make the "clear and compelling case for the liberal arts?"asked an alarmed report submitted to Congress a couple weeks ago.It's not hard.The most popular case,at the moment,is the preservationist one:The job of the humanities is "understanding,curating,and transmitting the first four thousand five hundred years of human consciousness,"as Columbia Sanskrit professor Sheldon Pollock put it at the Harvard gathering.Cultivating political character is another defense.The liberal

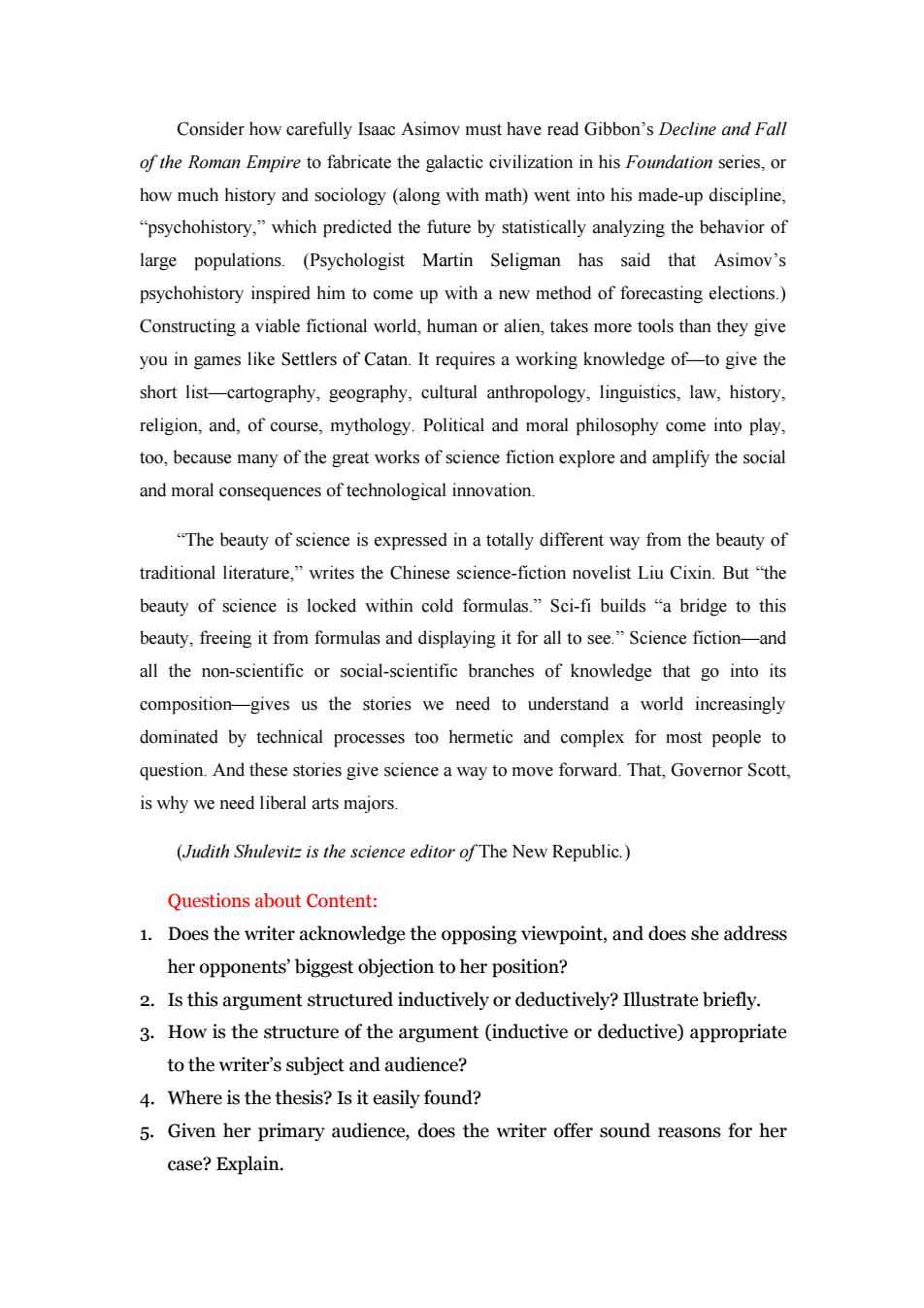

Why Do We Need the Liberal Arts? Because It Gives Us Sci-fi JUDITH SHULEVITZ The liberal arts are very old and very distinguished, and those who teach them are among the bitterest people I know. University presidents, trustees, and state legislatures are slashing their funding or getting rid of their subjects altogether. (French, German, Italian, and the classics will likely be the first to go.) Governor Rick Scott of Florida thinks that state universities should charge higher tuition to students who choose majors in fields that don’t lead directly to jobs. Even the social sciences are endangered: Republicans in Congress have been trying to pass an amendment to an appropriations bill that would forbid the National Science Foundation from funding any research in the human sciences not considered essential for America’s security or economic interests. Meanwhile, in their pristine new laboratories, the natural sciences thrive. “Spending for the humanities research in 2011 amounted to less than half of one percent of the amount dedicated to science and engineering research and development in the United States,” English professor Homi Bhabha said at a gloomy conference on the future of the humanities at Harvard in April, 2013. Illustration by Joe Wilson How does one make the “clear and compelling case for the liberal arts?” asked an alarmed report submitted to Congress a couple weeks ago. It’s not hard. The most popular case, at the moment, is the preservationist one: The job of the humanities is “understanding, curating, and transmitting the first four thousand five hundred years of human consciousness,” as Columbia Sanskrit professor Sheldon Pollock put it at the Harvard gathering. Cultivating political character is another defense. The liberal

arts education is said to give future citizens the historical perspective and ethical bent required to uphold democracy and avert totalitarianism.Then there's the answer that flips the question on its head:The humanities are good for questioning whether knowledge has to be good for anything.Personally,I find all of these arguments "clear and compelling,"but I worry that budget-conscious politicians and the heads of cash-starved institutions won't.If the criterion for funding areas of study must be that they add to American wealth and competitiveness,then I'd like to offer my own only half-unserious case for the liberal arts.I propose that they should survive,and thrive, because they give us science fiction,and science fiction creates jobs and makes us rich. Take any world-altering feat of engineering from the past century or so and science fiction probably dreamed it up first.Smithsonian Magazine recently published a list of ten such inventions.There's the submarine,one of whose most important architects was inspired by Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. (He received a congratulatory letter from Verne after he built the first vessel to operate successfully in open seas.)There's the modern helicopter,also inspired by a Verne novel (Clipper of the Clouds).The liquid-fueled rocket,invented by a man whose passion for interplanetary travel came from reading H.G.Wells's The War of the Worlds as a child.The nuclear chain reaction underlying atomic power,first envisioned in Wells's The World Set Free.The cell phone,modeled on the flip-top communicator used in Star Trek.And the inventor of Second Life has said that, although he'd been thinking about virtual worlds for years,Neal Stephenson's 1992 novel,Snow Crash,showed him what they might look like. The Smithsonian list left out a few other key collaborations between the literary and scientific imaginations.The most famous one is cyberspace,a term coined by William Gibson and fleshed out in his cyberpunk novel Neuromancer,which quickly expanded until it became virtually synonymous with the Internet.(The prescient Gibson also foresaw the rise of reality television.)Real computer networks weren't preceded by fictional ones,exactly-they were first suggested in an obscure 1963 memo describing an "Intergalactic Computer Network"-but they were given form by Ursula Le Guin,whose 1966 Rocannon's World introduced the "ansible,"a box-shaped instantaneous intergalactic communications device.Ansibles caught on

arts education is said to give future citizens the historical perspective and ethical bent required to uphold democracy and avert totalitarianism. Then there’s the answer that flips the question on its head: The humanities are good for questioning whether knowledge has to be good for anything. Personally, I find all of these arguments “clear and compelling,” but I worry that budget-conscious politicians and the heads of cash-starved institutions won’t. If the criterion for funding areas of study must be that they add to American wealth and competitiveness, then I’d like to offer my own only half-unserious case for the liberal arts. I propose that they should survive, and thrive, because they give us science fiction, and science fiction creates jobs and makes us rich. Take any world-altering feat of engineering from the past century or so and science fiction probably dreamed it up first. Smithsonian Magazine recently published a list of ten such inventions. There’s the submarine, one of whose most important architects was inspired by Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. (He received a congratulatory letter from Verne after he built the first vessel to operate successfully in open seas.) There’s the modern helicopter, also inspired by a Verne novel (Clipper of the Clouds). The liquid-fueled rocket, invented by a man whose passion for interplanetary travel came from reading H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds as a child. The nuclear chain reaction underlying atomic power, first envisioned in Wells’s The World Set Free. The cell phone, modeled on the flip-top communicator used in Star Trek. And the inventor of Second Life has said that, although he’d been thinking about virtual worlds for years, Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel, Snow Crash, showed him what they might look like. The Smithsonian list left out a few other key collaborations between the literary and scientific imaginations. The most famous one is cyberspace, a term coined by William Gibson and fleshed out in his cyberpunk novel Neuromancer, which quickly expanded until it became virtually synonymous with the Internet. (The prescient Gibson also foresaw the rise of reality television.) Real computer networks weren’t preceded by fictional ones, exactly—they were first suggested in an obscure 1963 memo describing an “Intergalactic Computer Network”—but they were given form by Ursula Le Guin, whose 1966 Rocannon’s World introduced the “ansible,” a box-shaped instantaneous intergalactic communications device. Ansibles caught on

and other authors put them into their own stories,including Orson Scott Card in Ender's Game (1985).That novel arguably also anticipated the use of computer games to teach,evaluate,and maybe manipulate students.Card's eerie"mind game," played by child cadets as part of their training at a grim"Battle School,"was designed both to grade their ability to think strategically and to sharpen their wits,although some students were pretty sure it was also meant to spy on and control them. "There is no science without fancy and no art without fact,"said Vladimir Nabokov,who was also a scientist (a self-taught butterfly expert and curator of lepidoptera at Harvard's zoology museum whose theories about the evolutionary history of a particular species of butterfly,once dismissed by better-credentialed colleagues,were recently vindicated by geneticists).Obviously,advances in science and technology take more than fancy.Constrained by the possible,scientists must work with heroic determination and settle for tiny steps forward amid the endless steps back.The novelist,on the other hand,may leap boldly into the future without regard for fact.But a great many science-fiction writers voluntarily hew to the laws of science,even while pushing them to their limits;it's fantasy writers who use magic, and even then,their magic has rules.And all science fiction,if it's any good,has to be plausible,if not in the sense that it might be true,then in the sense that it must feel true.Whether that happens has a lot to do with whether the writer can bring the characters to life,of course,but in science fiction,more perhaps than in other literary genres,suspension of disbelief depends on the quality of the author's"world-building," as sci-fi aficionados call it. HUMAMTIES RESEARCH 2011 24nTANKALs ES RESEARCH Illustration by Joe Wilson

and other authors put them into their own stories, including Orson Scott Card in Ender’s Game (1985). That novel arguably also anticipated the use of computer games to teach, evaluate, and maybe manipulate students. Card’s eerie “mind game,” played by child cadets as part of their training at a grim “Battle School,” was designed both to grade their ability to think strategically and to sharpen their wits, although some students were pretty sure it was also meant to spy on and control them. “There is no science without fancy and no art without fact,” said Vladimir Nabokov, who was also a scientist (a self-taught butterfly expert and curator of lepidoptera at Harvard’s zoology museum whose theories about the evolutionary history of a particular species of butterfly, once dismissed by better-credentialed colleagues, were recently vindicated by geneticists). Obviously, advances in science and technology take more than fancy. Constrained by the possible, scientists must work with heroic determination and settle for tiny steps forward amid the endless steps back. The novelist, on the other hand, may leap boldly into the future without regard for fact. But a great many science-fiction writers voluntarily hew to the laws of science, even while pushing them to their limits; it’s fantasy writers who use magic, and even then, their magic has rules. And all science fiction, if it’s any good, has to be plausible, if not in the sense that it might be true, then in the sense that it must feel true. Whether that happens has a lot to do with whether the writer can bring the characters to life, of course, but in science fiction, more perhaps than in other literary genres, suspension of disbelief depends on the quality of the author’s “world-building,” as sci-fi aficionados call it. Illustration by Joe Wilson WHAT THE FEDS FUND AT UNIVERSITIES

Consider how carefully Isaac Asimov must have read Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire to fabricate the galactic civilization in his Foundation series,or how much history and sociology (along with math)went into his made-up discipline, "psychohistory,"which predicted the future by statistically analyzing the behavior of large populations.(Psychologist Martin Seligman has said that Asimov's psychohistory inspired him to come up with a new method of forecasting elections.) Constructing a viable fictional world,human or alien,takes more tools than they give you in games like Settlers of Catan.It requires a working knowledge ofto give the short list-cartography,geography,cultural anthropology,linguistics,law,history, religion,and,of course,mythology.Political and moral philosophy come into play, too,because many of the great works of science fiction explore and amplify the social and moral consequences of technological innovation. "The beauty of science is expressed in a totally different way from the beauty of traditional literature,"writes the Chinese science-fiction novelist Liu Cixin.But "the beauty of science is locked within cold formulas."Sci-fi builds "a bridge to this beauty,freeing it from formulas and displaying it for all to see."Science fiction-and all the non-scientific or social-scientific branches of knowledge that go into its composition-gives us the stories we need to understand a world increasingly dominated by technical processes too hermetic and complex for most people to question.And these stories give science a way to move forward.That,Governor Scott, is why we need liberal arts majors. (Judith Shulevitz is the science editor ofThe New Republic.) Questions about Content: 1.Does the writer acknowledge the opposing viewpoint,and does she address her opponents'biggest objection to her position? 2.Is this argument structured inductively or deductively?Illustrate briefly. 3.How is the structure of the argument (inductive or deductive)appropriate to the writer's subject and audience? 4.Where is the thesis?Is it easily found? 5.Given her primary audience,does the writer offer sound reasons for her case?Explain

Consider how carefully Isaac Asimov must have read Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire to fabricate the galactic civilization in his Foundation series, or how much history and sociology (along with math) went into his made-up discipline, “psychohistory,” which predicted the future by statistically analyzing the behavior of large populations. (Psychologist Martin Seligman has said that Asimov’s psychohistory inspired him to come up with a new method of forecasting elections.) Constructing a viable fictional world, human or alien, takes more tools than they give you in games like Settlers of Catan. It requires a working knowledge of—to give the short list—cartography, geography, cultural anthropology, linguistics, law, history, religion, and, of course, mythology. Political and moral philosophy come into play, too, because many of the great works of science fiction explore and amplify the social and moral consequences of technological innovation. “The beauty of science is expressed in a totally different way from the beauty of traditional literature,” writes the Chinese science-fiction novelist Liu Cixin. But “the beauty of science is locked within cold formulas.” Sci-fi builds “a bridge to this beauty, freeing it from formulas and displaying it for all to see.” Science fiction—and all the non-scientific or social-scientific branches of knowledge that go into its composition—gives us the stories we need to understand a world increasingly dominated by technical processes too hermetic and complex for most people to question. And these stories give science a way to move forward. That, Governor Scott, is why we need liberal arts majors. (Judith Shulevitz is the science editor of The New Republic.) Questions about Content: 1. Does the writer acknowledge the opposing viewpoint, and does she address her opponents’ biggest objection to her position? 2. Is this argument structured inductively or deductively? Illustrate briefly. 3. How is the structure of the argument (inductive or deductive) appropriate to the writer’s subject and audience? 4. Where is the thesis? Is it easily found? 5. Given her primary audience, does the writer offer sound reasons for her case? Explain

6.Are you familiar with all those names mentioned in the essay?Please list at least one thing each individual is most famous for.You can refer to the Internet for information.List all new words to you. Questions about Organization 7.What strategy of expository development is used most in this essay? 8.Is the introduction effective for the intended audience?Explain. 9.What's the function of the chart and diagram in the essay?How do they contribute to the thesis? 10.By quoting Liu Cixin in the conclusion,what does the author want to deliver?Is it a good choice to quote in the end? Questions about Style 11.Comment on the quality of sentence variety in this essay. 12.How would you characterize the tone of the whole essay?And do you think it is appropriate for the intended audience? 13.Comment on the tone of the last sentence of this essay. Opinions for Essay Writing 14.To how much degree do you agree or disagree with the author's opinion? Use your own material to support your view,taking the specific Chinese conditions into consideration. 15.Which is your favorite sci-fi and why do you like it so much?How much is it possible for the imagination in that fiction to come into reality? Paraphrase 16.The job of the humanities is "understanding,curating,and transmitting the first four thousand five hundred years of human consciousness." 17.Then there's the answer that flips the question on its head:The humanities are good for questioning whether knowledge has to be good for anything. 18.There is no science without fancy and no art without fact. 19.Constrained by the possible,scientists must work with heroic determination and settle for tiny steps forward amid the endless steps

6. Are you familiar with all those names mentioned in the essay? Please list at least one thing each individual is most famous for. You can refer to the Internet for information. List all new words to you. Questions about Organization 7. What strategy of expository development is used most in this essay? 8. Is the introduction effective for the intended audience? Explain. 9. What’s the function of the chart and diagram in the essay? How do they contribute to the thesis? 10. By quoting Liu Cixin in the conclusion, what does the author want to deliver? Is it a good choice to quote in the end? Questions about Style 11. Comment on the quality of sentence variety in this essay. 12. How would you characterize the tone of the whole essay? And do you think it is appropriate for the intended audience? 13. Comment on the tone of the last sentence of this essay. Opinions for Essay Writing 14. To how much degree do you agree or disagree with the author’s opinion? Use your own material to support your view, taking the specific Chinese conditions into consideration. 15. Which is your favorite sci-fi and why do you like it so much? How much is it possible for the imagination in that fiction to come into reality? Paraphrase 16. The job of the humanities is “understanding, curating, and transmitting the first four thousand five hundred years of human consciousness.” 17. Then there’s the answer that flips the question on its head: The humanities are good for questioning whether knowledge has to be good for anything. 18. There is no science without fancy and no art without fact. 19. Constrained by the possible, scientists must work with heroic determination and settle for tiny steps forward amid the endless steps

back. 20.The novelist,on the other hand,may leap boldly into the future without regard for fact.But a great many science-fiction writers voluntarily hew to the laws of science,even while pushing them to their limits 21.Political and moral philosophy come into play,too,because many of the great works of science fiction explore and amplify the social and moral consequences of technological innovation

back. 20.The novelist, on the other hand, may leap boldly into the future without regard for fact. But a great many science-fiction writers voluntarily hew to the laws of science, even while pushing them to their limits 21. Political and moral philosophy come into play, too, because many of the great works of science fiction explore and amplify the social and moral consequences of technological innovation