Oral Physiology Department of Prosthodontics 2014.3

Oral Physiology Department of Prosthodontics 2014.3

INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION WHAT IS ORAL PHYSIOLOGY? Physiology is the branch of biology that deals with the study of functions of livingmatter.ral is the study of functions of the mouth and structures. For most organisms,beginning with those consisting of single cells,the fundamental function of the mouth is feeding.Because the oral cavity is the portal to the gastrointestinal tract,food materials are taken into the mouth. and swallowed.However,before these basic events occur,food has le rompt sources inte envromenann ta in the oral cavity it must be analyzed as suitable for entry into the gastrointestinal tract.A central focus of this book is to understand how the oral cavity performs the primary feeding functions of guiding food intake and preparing the food for swallowing and digestion. Another important function of the human mouth is speech production Although many animals use their mouths to produce various sounds,only humans use speech to communicate through language.This very important function involves sophisticated control of many oral,pharyngeal,and laryngeal structures to generate various sounds involved in speech production. humans;therefore,the role of the oral cavity as a prehensile organ and other more minor functions will not be considered in this course. HOW THE FUNCTIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY ARE ORGANIZED mplex ction like fe ding involves many different b dy areas,and at the level of the mouth,feeding consists of several basic levels of organization. First,food is selected and analyzed by a number of sensory systems including those involved in taste,smell,touch,and temperature perception of enters in the central nervous system.Based on central integration,saliva is secreted. chewing movements begin,and swallowing eventually occurs.Each of these basic levels of organization involves additional phases of complexity.For example,additional sensory systems are needed in the control of muscle rotect of the oral struct om tissue rereor walling.These basic levelsof ee fr dar while taste perception,neuromuscular control of mastication,and salivary secretion are themselves complex functions.To understand these behaviors requires an in-depth analysis of each system including receptor mechanisms,central -1-

INTRODUCTION - 1 - INTRODUCTION WHAT IS ORAL PHYSIOLOGY? Physiology is the branch of biology that deals with the study of functions of livingmatter. Oral physiology, therefore, is the study of functions of the mouth and associated structures. For most organisms, beginning with those consisting of single cells, the fundamental function of the mouth is feeding. Because the oral cavity is the portal to the gastrointestinal tract, food materials are taken into the mouth, chewed, and swallowed. However, before these basic events occur, food has to be selected from potential sources in the environment, and when taken into the oral cavity it must be analyzed as suitable for entry into the gastrointestinal tract. A central focus of this book is to understand how the oral cavity performs the primary feeding functions of guiding food intake and preparing the food for swallowing and digestion. Another important function of the human mouth is speech production. Although many animals use their mouths to produce various sounds, only humans use speech to communicate through language. This very important function involves sophisticated control of many oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal structures to generate various sounds involved in speech production. Other possible functions of the oral cavity could be suggested, such as holding objects; while this function is quite important in animals, it is trivial in humans; therefore, the role of the oral cavity as a prehensile organ and other more minor functions will not be considered in this course. HOW THE FUNCTIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY ARE ORGANIZED A complex function like feeding involves many different body areas, and, at the level of the mouth, feeding consists of several basic levels of organization. First, food is selected and analyzed by a number of sensory systems including those involved in taste, smell, touch, and temperature perception of the food. This sensory information is then integrated by various centers in the central nervous system. Based on central integration, saliva is secreted, chewing movements begin, and swallowing eventually occurs. Each of these basic levels of organization involves additional phases of complexity. For example, additional sensory systems are needed in the control of muscle movements and protection of the oral structures from tissue damage while food is prepared for swallowing. These basic levels of organization such as taste perception, neuromuscular control of mastication, and salivary secretion are themselves complex functions. To understand these behaviors requires an in-depth analysis of each system including receptor mechanisms, central

INTRODUCTION pathways convevina information to the brain neural connections used in integrating sensory information,neurotransmitters for synaptic transmission, motor inte and mechanisms.By systems,we can understand the more complex behavior of the role of the oral cavity in feeding. THE IMPORTANCE OF THE STUDY OF ORAL PHYSIOLOGY Most of the information contained in this course derives from work of in basicbio mechanisms their findings nave resulted in remarkable progress in understanding orofacial function.These major advances are not only interesting in themselves,but also lead to explanations of orofacial dysfunctions and suggest better methods of diagnosis and treatment strategies.Many examples could be mentioned here. one interesting study centered on the very familiar phenomenon commonly referred to as a "sweet tooth.' In more technical terms a "sweet tooth"is the exaggerated preference behavior resulting from stimulation of taste receptors with certain classes of chemicals.Sweet foods motivate consumption,so sweeteners are added to a broad variety of prep foods to age pu and Unfortunately.this behavior can lad to severe heath pro ems including obesity and dental decay.It is therefore important to study the basic mechanisms of this phenomenon,and this has taken place at several levels. Neuroscientists have studied sweet taste receptor mechanisms and explored the coding of sweet taste by the central nervous system.Psychologists have experiments toexp aspects of sweet ta aste.As a rof these and other mulidspnay studies.I ha b posible to design sweeteners that have little or no caloric content,that do not act as a substrate for fermentation by oral bacteria,and that therefore do not result in tooth decay.In recent years,these alterative sweeteners have become common in m any so- alle diet fo ods.By fooling the taste system that evolved select swe sting,nutritious foods,we can experience the indulgence of sweet-tasting foods without some of the health-related consequences.In this example,scientists interested in how the taste system processes neural signals from chemicals placed on the tongue have contributed to major snov halth probicms and haveomed eetener industry as well Other examples could be given to detail how basic research has contributed to the understanding of clinical problems.Until the elementary biology of the orofacial region and the central nervous system control of orofacial structures is better understood,progress in clinical diagnosis and treatment of ny disorders wil al.This is anin troduction to the exciting work that has occurred in the study of the function of the mouth and associated structures. -2

INTRODUCTION - 2 - pathways conveying information to the brain, neural connections used in integrating sensory information, neurotransmitters for synaptic transmission, motor integrating systems, and peripheral effector mechanisms. By analyzing these fundamental systems, we can understand the more complex behavior of the role of the oral cavity in feeding. THE IMPORTANCE OF THE STUDY OF ORAL PHYSIOLOGY Most of the information contained in this course derives from work of investigators interested in basic biologic mechanisms; their findings have resulted in remarkable progress in understanding orofacial function. These major advances are not only interesting in themselves, but also lead to explanations of orofacial dysfunctions and suggest better methods of diagnosis and treatment strategies. Many examples could be mentioned here, but one interesting study centered on the very familiar phenomenon commonly referred to as a "sweet tooth." In more technical terms a "sweet tooth" is the exaggerated preference behavior resulting from stimulation of taste receptors with certain classes of chemicals. Sweet foods motivate consumption, so sweeteners are added to a broad variety of prepared foods to encourage purchase and consumption. Unfortunately, this behavior can lead to severe health problems including obesity and dental decay. It is therefore important to study the basic mechanisms of this phenomenon, and this has taken place at several levels. Neuroscientists have studied sweet taste receptor mechanisms and explored the coding of sweet taste by the central nervous system. Psychologists have designed experiments to explore the motivational aspects of sweet taste. As a result of these and other multidisciplinary studies, it has become possible to design sweeteners that have little or no caloric content, that do not act as a substrate for fermentation by oral bacteria, and that therefore do not result in tooth decay. In recent years, these alternative sweeteners have become common in many so-called diet foods. By fooling the taste system that evolved to select sweet-tasting, nutritious foods, we can experience the indulgence of sweet-tasting foods without some of the health-related consequences. In this example, scientists interested in how the taste system processes neural signals from chemicals placed on the tongue have contributed to major progress in controlling at least two serious health problems and have spawned a multimillion dollar artificial sweetener industry as well. Other examples could be given to detail how basic research has contributed to the understanding of clinical problems. Until the elementary biology of the orofacial region and the central nervous system control of orofacial structures is better understood, progress in clinical diagnosis and treatment of many disorders will remain empirical.This is an introduction to the exciting work that has occurred in the study of the function of the mouth and associated structures

DENTITION CHAPTER 1.DENTITION DENTITION CONCEPTS DENTITION:the teeth in the dental arch. PRIMARY DENTITION:the teeth that erupt first and are normally shed and replaced by permanent (succedaneous)teeth.Also called:DECIDUOUS ENTITION PERMANENT DENTITION:the teeth that erupt after the primary dentition that do not shed under normal conditions. MIXED DENTITION:a stage of development during which the primary and permanent teeth function together in the mouth.Also called:TRANSITIONAL ON Humans have two sets of teeth in their lifetime.The first set of teeth to be seen in the mouth is the primary or deciduous dentition,which begins to prenatally at about 14 weeks in utero and is co m leted postnatally at f age.In the absenc of congenital disorders,dental disease or trauma,the first teeth in this dentition begin to appear in the oral cavity at the mean age of 6.and the last emerge at a mean age of 28t4 months.The deciduous dentition remains intact(barring loss from dental caries or trauma) until the child is about 6 years of age At about that time the first succeda neous or permanent teeth begin to emerge into the mouth.The emergence of these teeth begins the transitional or mixed dentition period in which there is a mixture of deciduous and succedaneous teeth present.The transition period lasts from about 6 to 12 years of age and ends when all the deciduous teeth have been shed.At that time the pe nanent dentition pe od be gins Thus,t transition from h primary dentition to the permanent dentition begins with the emergence of the first permanent molars,shedding of the deciduous incisors,and emergence of the permanent incisors.The mixed dentition period is often a difficult time for the young child because of habits,missing teeth,teeth of different colors and wding of the teeth,and malpose teeth The permanent,or suc edaneous,teeth replace the exfoliated deciduous teeth in a sequence of eruption that exhibits some variance.After the shedding of the deciduous canines and molars,emergence of the permanent canines and premolars,and emergence of the second permanent molars,the -3-

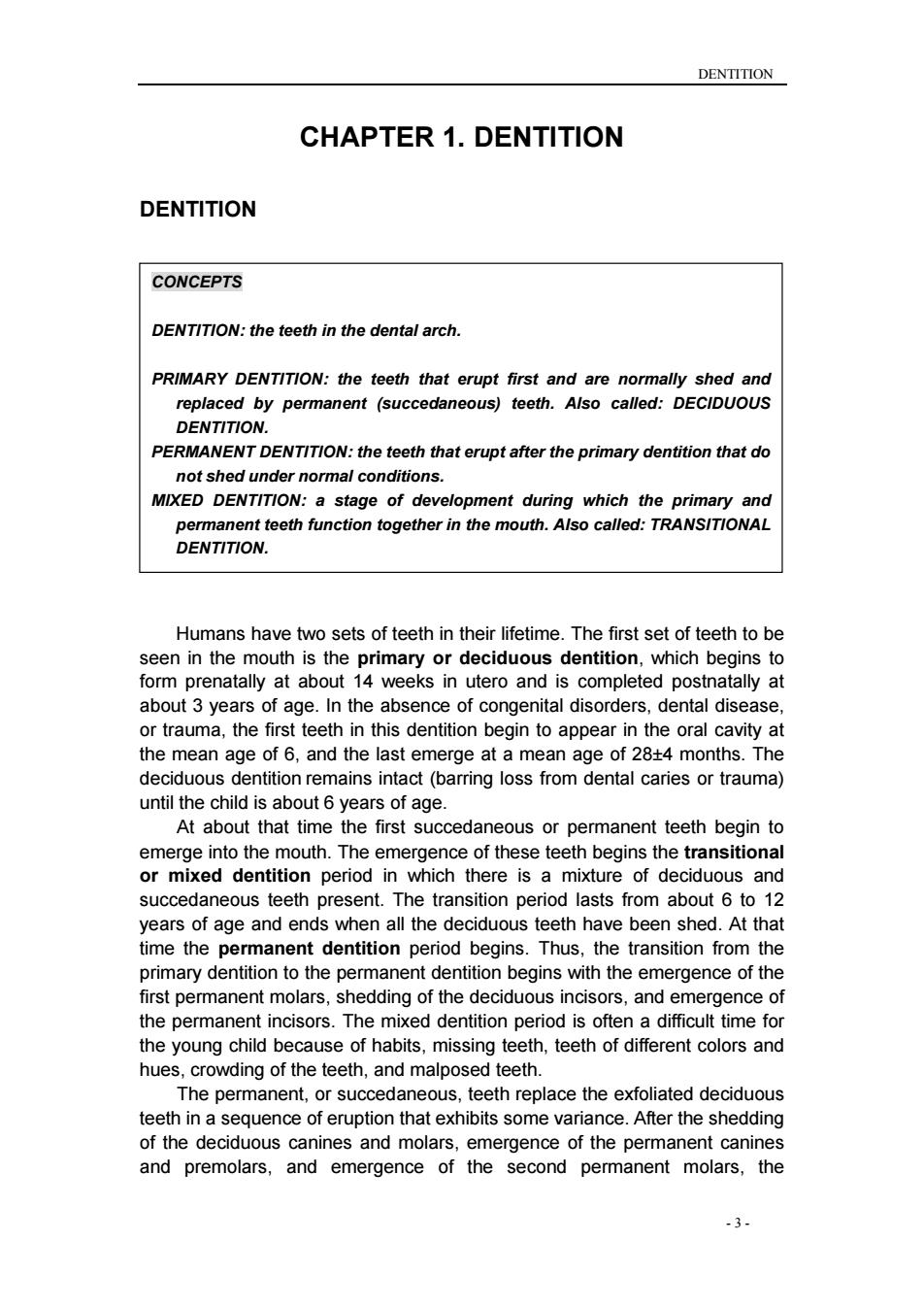

DENTITION - 3 - CHAPTER 1. DENTITION DENTITION Humans have two sets of teeth in their lifetime. The first set of teeth to be seen in the mouth is the primary or deciduous dentition, which begins to form prenatally at about 14 weeks in utero and is completed postnatally at about 3 years of age. In the absence of congenital disorders, dental disease, or trauma, the first teeth in this dentition begin to appear in the oral cavity at the mean age of 6, and the last emerge at a mean age of 28±4 months. The deciduous dentition remains intact (barring loss from dental caries or trauma) until the child is about 6 years of age. At about that time the first succedaneous or permanent teeth begin to emerge into the mouth. The emergence of these teeth begins the transitional or mixed dentition period in which there is a mixture of deciduous and succedaneous teeth present. The transition period lasts from about 6 to 12 years of age and ends when all the deciduous teeth have been shed. At that time the permanent dentition period begins. Thus, the transition from the primary dentition to the permanent dentition begins with the emergence of the first permanent molars, shedding of the deciduous incisors, and emergence of the permanent incisors. The mixed dentition period is often a difficult time for the young child because of habits, missing teeth, teeth of different colors and hues, crowding of the teeth, and malposed teeth. The permanent, or succedaneous, teeth replace the exfoliated deciduous teeth in a sequence of eruption that exhibits some variance. After the shedding of the deciduous canines and molars, emergence of the permanent canines and premolars, and emergence of the second permanent molars, the CONCEPTS DENTITION: the teeth in the dental arch. PRIMARY DENTITION: the teeth that erupt first and are normally shed and replaced by permanent (succedaneous) teeth. Also called: DECIDUOUS DENTITION. PERMANENT DENTITION: the teeth that erupt after the primary dentition that do not shed under normal conditions. MIXED DENTITION: a stage of development during which the primary and permanent teeth function together in the mouth. Also called: TRANSITIONAL DENTITION

DENTITION permanent dentition is completed(including the roots)at about 14 to 15 years of age,except for the third molars.which are completed at 18 to 25 years of age.durain of the isyears.The missing,which may be the case.(See figure 1-1) MAXILLARY Centralincisor (first incisor Second mole Second mola First molar (second incisor Central incisor(first incisor) MANDIBULAR Central incisor (first incisor) ateral incisor(second incisor) Canine (cuspid) (c) Second premolar (second bic First molar Second mola FIGURE1-1.A.Casts of primary dentition.B.Casts of per nt dentition -4

DENTITION - 4 - permanent dentition is completed (including the roots) at about 14 to 15 years of age, except for the third molars, which are completed at 18 to 25 years of age. In effect, the duration of the permanent dentition period is l2+ years. The completed permanent dentition consists of 32 teeth if none are congenitally missing, which may be the case. (See figure 1-1) FIGURE 1-1. A. Casts of primary dentition. B. Casts of permanent dentition

DENTITION Dental arch form The teeth are positioned on the maxilla and mandible in such a way as to produce a curved arch when viewed from the occlusal surface (Figure 1-2) This arch form is in large part determined by the shape of the underlying basal bone. The basic pattern of tooth position is the arch.on the basis of qualitative anth opologists general shape of the palatal ara being paraboioid.Usolipsoid.rotund.and have des horseshoe-shaped.An arch has long been known architecturally (as the word architecture itself implies)as a strong,stable arrangement with forces being transmitted normal to the apex of a catenary curve.The shape of the arch form of the facial surfaces of the teeth was thought by Currier to be a segment of an In the past,interest in arch form was directed toward finding an"ideal"or basic mean arch form pattern that functionally interrelates alveolar bone and teeth and could have clinical application.However,any ideal arch pattem tends toignore variance.a linical reality which suggests that adaptation mechanisms are more imp tant for occ sal stability than any ideal emplate Changes in arch form,within anatomical limits,do not have any significant effect on occlusion unless the change is in only one of the two dental arches. Discrepancies in arch form between the maxillary and mandibular arches positioned,as in severe mandibular retrognathism or rogathism.nsuch cases,the arch form distortion in one arch allows a better occlusion on the posterior aspect than is otherwise possible. Figure 1-2 The curvature of the maxillary (A)and 5

DENTITION - 5 - Dental arch form The teeth are positioned on the maxilla and mandible in such a way as to produce a curved arch when viewed from the occlusal surface (Figure 1-2). This arch form is in large part determined by the shape of the underlying basal bone. The basic pattern of tooth position is the arch. On the basis of qualitative observations, anthropologists have described the general shape of the palatal arch as being paraboloid, U-shaped, ellipsoid, rotund, and horseshoe-shaped. An arch has long been known architecturally (as the word architecture itself implies) as a strong, stable arrangement with forces being transmitted normal to the apex of a catenary curve. The shape of the arch form of the facial surfaces of the teeth was thought by Currier to be a segment of an ellipse. In the past, interest in arch form was directed toward finding an "ideal" or basic mean arch form pattern that functionally interrelates alveolar bone and teeth and could have clinical application. However, any ideal arch pattern tends to ignore variance, a clinical reality which suggests that adaptation mechanisms are more important for occlusal stability than any ideal template. Changes in arch form, within anatomical limits, do not have any significant effect on occlusion unless the change is in only one of the two dental arches. Discrepancies in arch form between the maxillary and mandibular arches generally result in poor occlusal relationships. Arch form distortion in only one arch can be advantageous when the basal bone structure is incorrectly positioned, as in severe mandibular retrognathism or prognathism. In such cases, the arch form distortion in one arch allows a better occlusion on the posterior aspect than is otherwise possible. Figure 1-2 The curvature of the maxillary (A) and

DENTITION mandibular(B)arches as seen from the occlusal (horizontal)plane. FIGURE1-3 The torms overjet and overbite are commonly used to describe horizontal and vertica overlap of teeth. Overlap of the teeth CONCEPTS OVERJET:the projection of teeth beyond their antagonists in the horizonta OVERBITE:the distance teeth lap over their antagonists as measured vertically. Also called:vertical overlap. The arch form of the maxilla tends to be larger than that of the mandible As a result,the eth "overh th dibular teeth when n the teeth are in centric occlusion(the position of maximal intercuspation).The lateral o anteroposterior aspect of this overhang is called overiet,a term that can be made more specific as indicated in Figure 1-3.This relationship of the arches and teeth has functional significance,including the possibility of increased duration of occlusal contacts in protrusive and lateral movements in incising mastication.The of vertica and horizon erlap has to be related to mastication,jaw mo ments,spe ech,type of diet,and esthetics Excessive vertical overlap of the anterior teeth may result in tissue impingement and is referred to as an impinging overbite.Correction is not a matter of trying to increase vertical dimension by restorations on posterior eeth. Orthodontics generally required and sometimes orthognathic surgery is recommended Gingivitis and periodontitis may occur from continued impinging overbite The degree of vertical and horizontal overlap should be sufficient to allow jaw movement in function without interference.There should be sufficient vertical overlap(with the cuspid providing the primary guidance)to enable the usion of the posterio eth.Such mo ovement in ma ticatory function is controlled by neuromuscular mechanisms developed out of past learning in relation to physical contact of the teeth.When protective reflexes are bypassed in parafunction.trauma from occlusion involving the teeth.supporting structures,and TMJs may occur.However,aside from cheek biting as a result of insufficient horizontal overlap of the molars and trau a to the iva fror an impinging overbite,no convincing evidence shows that a certain degree of overbite or overjet is optimal for effective mastication or stability of the occlusion.Providing the correct vertical and/or horizontal overlap requires .6-

DENTITION - 6 - mandibular (B) arches as seen from the occlusal (horizontal) plane. FIGURE 1-3 The terms overjet and overbite are commonly used to describe horizontal and vertical overlap of teeth. Overlap of the teeth The arch form of the maxilla tends to be larger than that of the mandible. As a result, the maxillary teeth "overhang" the mandibular teeth when the teeth are in centric occlusion (the position of maximal intercuspation). The lateral or anteroposterior aspect of this overhang is called overjet, a term that can be made more specific as indicated in Figure 1-3. This relationship of the arches and teeth has functional significance, including the possibility of increased duration of occlusal contacts in protrusive and lateral movements in incising and mastication. The significance of vertical and horizontal overlap has to be related to mastication, jaw movements, speech, type of diet, and esthetics. Excessive vertical overlap of the anterior teeth may result in tissue impingement and is referred to as an impinging overbite. Correction is not simply a matter of trying to increase vertical dimension by restorations on posterior teeth. Orthodontics is generally required, and sometimes orthognathic surgery is recommended. Gingivitis and periodontitis may occur from continued impinging overbite. The degree of vertical and horizontal overlap should be sufficient to allow jaw movement in function without interference. There should be sufficient vertical overlap (with the cuspid providing the primary guidance) to enable the disocclusion of the posterior teeth. Such movement in masticatory function is controlled by neuromuscular mechanisms developed out of past learning in relation to physical contact of the teeth. When protective reflexes are bypassed in parafunction, trauma from occlusion involving the teeth, supporting structures, and TMJs may occur. However, aside from cheek biting as a result of insufficient horizontal overlap of the molars and trauma to the gingiva from an impinging overbite, no convincing evidence shows that a certain degree of overbite or overjet is optimal for effective mastication or stability of the occlusion. Providing the correct vertical and/or horizontal overlap requires CONCEPTS OVERJET: the projection of teeth beyond their antagonists in the horizontal plane. Also called: horizontal overlap OVERBITE: the distance teeth lap over their antagonists as measured vertically. Also called: vertical overlap

DENTITION appropriate knowledge of dental morphology,esthetics,phonetics.restorative dentistry function and orthodontics The ove apping of the maxillary teeth over the mandibular teeth has a protective feature:during opening and closing movements of the jaws,the cheeks,lips,and tongue are less likely to be caught.Because the facial occlusal margins of the maxillary teeth extend beyond the facial occlusal margins of the mandibular teeth and the linguo-occlusal margins of the m dibular teeth e extend lingually in relation to linguo occ nargins of the maxillary teeth,the soft tissues are displaced during the act of closure unti the teeth have had an opportunity to come together in occlusal contact.Cheek biting is commonly associated with dental restorations of second permanent molars that have been made with an end-to-end occlusal relationship(i.e., without overjet). Curvatures of occlusal planes CONCEPTS CURVE OF SPEE:the anatomic curve established by the occlusal alignment of the teeth,as projected onto the median plane,beginning with the cusp tipo the mandibular canine and following the buccal cusp tips of the premola and molar teeth.continuing through the anterior border of the mandibulai ramus,ending with the anterior most portion of the mandibular condyle.First described by Ferdinand Graf Spee.German anatomist.in 1890. CURVE OF WILSON:in the man dibular arch,that curve(viewed in the frontal plane)which is concave above and contacts the buccal and lingual cusp tips of the mandibular molars:in the maxillary arch,that curve (viewed in the frontal plane)which is convex below and contacts the buccal and lingual cuso tios of the maxillary molars CURVE OF MONSON:a proposed ideal curve of occlusion in which each cusp and incisa edge touches or conforms to a segment of the s rfac e of sphere 8 inches in diameter with its center in the region of the glabella The occlusal surfaces of the dental arches do not generally conform to a flat plane (.g the mandibular arch has one or ved planes conforming to the arrangement of the te ethinthe dental arches).th most well known is the curve of Spee,who noted that the cusps and incisal ridges of the teeth tended to display a curved alignment when the arches were observed from a point opposite the first molars.This alignment(Figure 1-4)is -7

DENTITION - 7 - appropriate knowledge of dental morphology, esthetics, phonetics, restorative dentistry, function, and orthodontics. The overlapping of the maxillary teeth over the mandibular teeth has a protective feature: during opening and closing movements of the jaws, the cheeks, lips, and tongue are less likely to be caught. Because the facial occlusal margins of the maxillary teeth extend beyond the facial occlusal margins of the mandibular teeth and the linguo-occlusal margins of the mandibular teeth extend lingually in relation to the linguo-occlusal margins of the maxillary teeth, the soft tissues are displaced during the act of closure until the teeth have had an opportunity to come together in occlusal contact. Cheek biting is commonly associated with dental restorations of second permanent molars that have been made with an end-to-end occlusal relationship (i.e., without overjet). Curvatures of occlusal planes The occlusal surfaces of the dental arches do not generally conform to a flat plane (e.g., the mandibular arch has one or more curved planes conforming to the arrangement of the teeth in the dental arches). Perhaps the most well known is the curve of Spee, who noted that the cusps and incisal ridges of the teeth tended to display a curved alignment when the arches were observed from a point opposite the first molars. This alignment (Figure 1-4) is CONCEPTS CURVE OF SPEE: the anatomic curve established by the occlusal alignment of the teeth, as projected onto the median plane, beginning with the cusp tip of the mandibular canine and following the buccal cusp tips of the premolar and molar teeth, continuing through the anterior border of the mandibular ramus, ending with the anterior most portion of the mandibular condyle. First described by Ferdinand Graf Spee, German anatomist, in 1890. CURVE OF WILSON: in the mandibular arch, that curve (viewed in the frontal plane) which is concave above and contacts the buccal and lingual cusp tips of the mandibular molars; in the maxillary arch, that curve (viewed in the frontal plane) which is convex below and contacts the buccal and lingual cusp tips of the maxillary molars. CURVE OF MONSON: a proposed ideal curve of occlusion in which each cusp and incisal edge touches or conforms to a segment of the surface of a sphere 8 inches in diameter with its center in the region of the glabella

DENTITION spoken of as the curve or curve of Spee.This curvature is within the sagittal plane only.Monson visualized a three-dimensional spherical curvature invong both theight and bicuspid and moar cuspsa nd the right and lef condyles.It was supposed that the center of a sphere with an 8-inch diamete was the vector for converging lines of masticatory forces passing through the center of the teeth and that the occlusal surfaces of the molar teeth were conaruent with the surface of a sphere of some dimension.although the idea was incorporated into complete dentures and the design of some early articulators. uch curvature has not been accepted as a goal o of treatment ever for dentures.However,the curvature of the occlusal plane such as the curve of Spee does have clinical significance in relation to tooth guidance,that is, canine and/or incisal guidance as applied in orthodontics and restorative dentistry.In these,disocclusion of the posterior teeth is desired during anterior (protrusive)movements in protrusive movements and to decrease the frequency of relapse. FIGURE 1-4.Curve of Spee Inclination and angulation of the roots of the teeth The relationship of the axes of the maxillary and mandibular teeth to each other varies with each tooth group (ie incisors canines premolars and molars).as illustrated in Figure1 Knowing bout the relativeroo ange has several uses:(1)it aids in visualizing how the x-ray beam must be directed to obtain true normal projections of the roots of the teeth;(2)it helps relate the direction of occlusal forces in restorations along the long axis of the teeth;(3)it guides control of orthodontic forces for proper angulations of the teeth;(4)and with the right angulations No absolute rules may be assumed when describing the axial relations of maxillary and mandibular teeth in centric occlusion.Each tooth must be placed at the angle that best withstands the lines of force brought against it during -8-

DENTITION - 8 - spoken of as the curve or curve of Spee. This curvature is within the sagittal plane only. Monson visualized a three-dimensional spherical curvature involving both the right and left bicuspid and molar cusps and the right and left condyles. It was supposed that the center of a sphere with an 8-inch diameter was the vector for converging lines of masticatory forces passing through the center of the teeth and that the occlusal surfaces of the molar teeth were congruent with the surface of a sphere of some dimension. Although the idea was incorporated into complete dentures and the design of some early articulators, such curvature has not been accepted as a goal of treatment even for dentures. However, the curvature of the occlusal plane such as the curve of Spee does have clinical significance in relation to tooth guidance, that is, canine and/or incisal guidance as applied in orthodontics and restorative dentistry. In these, disocclusion of the posterior teeth is desired during anterior (protrusive) movements in protrusive movements and to decrease the frequency of relapse. FIGURE 1-4. Curve of Spee. Inclination and angulation of the roots of the teeth The relationship of the axes of the maxillary and mandibular teeth to each other varies with each tooth group (i.e., incisors, canines, premolars, and molars), as illustrated in Figure 1-5. Knowing about the relative root angles has several uses: (1) it aids in visualizing how the x-ray beam must be directed to obtain true normal projections of the roots of the teeth; (2) it helps relate the direction of occlusal forces in restorations along the long axis of the teeth; (3) it guides control of orthodontic forces for proper angulations of the teeth; (4) and it aids in using templates to place dental implants with the right angulations. No absolute rules may be assumed when describing the axial relations of maxillary and mandibular teeth in centric occlusion. Each tooth must be placed at the angle that best withstands the lines of force brought against it during

DENTITION function.The angle at which it is placed depends on the function the tooth has laced atsanevity may beatisk Althoughitisone of the principles of clinical practice to cclusal fo aorghelong9soiieeipr9ctcalPenods9otapieaionlhai principle clinically by determining such a force vector have yet to be established.The anterior teeth seem to be placed at a disadvantage when viewed from mesial or distal aspects.The lines offeree during mastication or during the ot t cthestd that teine m openin jaws are tan gent generally to the momentary biting and shearing only and not for the assumption of the full force of the jaws.Neuromuscular control mechanisms are highly developed for the control of such transient forces.The mesiodistal and faciolingual axial between the ongaxis of a tooth and aline drawn perpendicular to a horiz ntal plane.The axial inclinations of the teeth and roots vary,but in general,they appear to correspond favorably to the data summarized in Box 1-1 UPPER MOLARS ROOTED TEETH R MOLARS Distal root FIGURE 1-5.Orientation of the crowns and roots

DENTITION - 9 - function. The angle at which it is placed depends on the function the tooth has to perform. If the tooth is placed at a disadvantage, its longevity may be at risk. Although it is one of the principles of clinical practice to direct occlusal forces along the long axis of the teeth, practical methods for application of that principle clinically by determining such a force vector have yet to be established. The anterior teeth seem to be placed at a disadvantage when viewed from mesial or distal aspects. The lines offeree during mastication or during the mere opening or closing of the jaws are tangent generally to the long axes of these teeth. It has been suggested that they are designed for momentary biting and shearing only and not for the assumption of the full force of the jaws. Neuromuscular control mechanisms are highly developed for the control of such transient forces. The mesiodistal and faciolingual axial inclinations of the teeth are usually described in terms of angles between the long axis of a tooth and a line drawn perpendicular to a horizontal plane. The axial inclinations of the teeth and roots vary, but in general, they appear to correspond favorably to the data summarized in Box 1-1 FIGURE 1-5. Orientation of the crowns and roots