NBER WORKING PAPERS SERIES NONRATIONAL ACTORS AND FINANCIAL MARKET BEHAVIOR Richard Zeckhauser Jayendu Patel Darryll Hendricks Working Paper No.3731 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge,MA 02138 June 1991 Zeckhauser is also affiliated with the National Bureau of Economic Research.Please direct correspondence to 79 JFK St., Cambridge,MA02138,U.s.A.(phone:617-495-1393,fax:617-495- 1972).The research was partially funded by the Decision,Risk, and Management Science Program of the National Science Foundation.This paper is forthcoming in Theory and Decision. This paper is part of NBER's research program in Financial Markets and Monetary Economics.Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research

NBER Working Paper #3731 June 1991 NONRATIONAL ACTORS AND FINANCIAL MARKET BEHAVIOR ABSTRACT The insights of descriptive decision theorists and psychologists,we believe,have much to contribute to our understanding of financial market macrophenomena.We propose an analytic agenda that distinguishes those individual idiosyncrasies that prove consequential at the macro-level from those that are neutralized by market processes such as poaching. We discuss five behavioral traits barn-door closing, expert/reliance effects,status quo bias,framing,and herding that we employ in explaining financial flows.Patterns in flows to mutual funds,to new equities,across national boundaries,as well as movements in debt-equity ratios are shown to be consistent with deviations from rationality. Richard Zeckhauser Jayendu Patel Darryll Hendricks John F.Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Cambridge,MA 02138

Nonrational Actors and Financial Market Behavior Are financial markets efficient?Do their participants behave rationally?Does a positive answer to the second question imply a positive answer to the first?And vice versa?These remain open questions despite decades of effort by economists and numerous claims that the issues have been resolved. Financial markets are extremely competitive (with near-instantaneous price adjustments and little room for strategic behavior),with virtually no externalities from participants' actions.Under such conditions,individual rationality can aggregate to collectively efficient outcomes.A body of work developing this view was honored by the Nobel Committee in Economics when it awarded its 1990 prize to modem finance's pioneers,Harry Markowitz, Merton Miller,and William Sharpe.But does this paradigm capture most financial market behavior? Clearly,some of the participants in financial markets do not act with perfect rationality; that is,they make mistakes.But more astute players stand ready to capitalize on their mistakes-for example,to buy when panic leads to speculative market crashes,to extract 1/8s and 1/4s from individuals who trade in and out in the mistaken belief that they can beat the market,or to take positions to bring mispriced stocks into line.Given this sort of "poaching" (which includes arbitrage),the collective outcome may be indistinguishable from the one that would result if all participants behaved with perfect rationality. Consequently,one might expect to find few instances of nonrational financial behavior at aggregate levels.But then how can we account for speculative fads,from the Dutch tulip mania of the seventeenth century to the rash of junk bonds in the 1980s (see Shiller,1989)?2 Equally puzzling is the crash of October 1987,which reduced the stock market's value by one- third,although no significant bad news had broken.Such events hint that the rationality paradigm may not be universally applicable,but since each case is unique in important respects,their true cumulative significance is difficult to interpret. Academic attempts to identify inefficient aggregate behavior,or to refute the assumption of a rational representative agent,have focused predominantly on asset prices.Shiller's(1981, For our purposes.anonrational or irrational agent is simply one who differs from the neclassical homo cconomicus prototype characterized by Von Neumann-Morgenstern utility.optimal expectations.Bayesian updating rules for probability revision,and so on.The yualifier "behavioral."in our paper.is interchangeable with "nonrational,"and carries no pejorative connotations. 2Bad overall outcomes can result from good individual choices as well as from poor ones.In this spirit.the economist explains various undesirable social phenomena.from unemplyment to traffic congestion.as collectively suboptimal outcomes that result from rational individual choices(Schelling.1978)

-2- 1989)work,arguing that the equity prices are excessively volatile relative to dividend streams, is a hotly debated example.3 In this paper,we focus instead on the evidence from financial flows,which like asset prices are regular(not idiosyncratic)and therefore provide a usable database.From a policy standpoint such flows are of vital concem since they represent the investment patterns of our economy.4 We will argue that patters in various types of flows-to mutual funds,to new equities, across national boundaries-are consistent with deviations from rationality.The insights of descriptive decision theorists and psychologists,we believe,have much to contribute to our understanding of such financial market macrophenomena.We propose an analytic agenda that distinguishes those individual idiosyncrasies that prove consequential at the macro-level from those that are neutralized by market processes such as poaching. The plan of the paper is as follows.5 Section I sketches the current state of the efficient markets paradigm,and contrasts it with behavioral phenomena relevant to the study of financial market outcomes.Section 2 highlights selected empirical results that show these behavioral factors at work.Section 3 discusses further applications of the behavioral approach in finance,and section 4 concludes. 1.Behavioral foundations of financial macrophenomena We focus on behavior as it is revealed in market outcomes,rather than approach our subject through surveys or controlled experiments.6 One would expect financial market outcomes to avoid certain kinds of nonrationality that might appear under experimental conditions,because investors play for significant stakes and have sustained opportunities for practice.In experimental markets that permit practice and significant payment,Camerer (1987)has found that many anomalies vanish,although individuals continue to suffer from 3Also see the anomalies columns in the Journal of Economie Perspectives Vol.1,1987,and subscquent issuesl. and references in Leroy,1989,section VIl. The finance academy sheepishly acknowledges the relative lack of work on this topic.For example,Ross (1989. p.94)admits that"there can be nothing more embarrassing to an ecoomist than the ability to explain the price in a market while being completely silent on the quantity."He suggests that the only way to explain the volume of financial trade is with a model that.while rational,permits divergent and changing opinions. SPatel,Zeckhauser,and Hendricks(1991a)briefly review a portion of the material discussed here. we sidestep the philosophical debate on whether models should be judged by the realism of their assumptions or the accuracy of their predictions-for instance.see Friedman (1953)and the vast subsequent literature.In the present context,this debate would focus on whether good models must make realistic assumptions about individual behavior.or need only make accurate predictions about aggregate outcomes

-3- representativeness bias(Kahneman,Slovic and Tversky,1982;Arrow,1982).7 Camerer concludes that "a program of empirical work...could establish what kinds of nonrationality seem to persist under the incentives and leaming opportunities present in natural markets. Such data might lead to economic theory that uses evidence of systematic nonrationality to make better predictions."We accept this challenge and ask:what decision-making biases remain in operating financial markets,where payoffs are significant,poaching is frequently possible,information is extensive and material,and most players participate repeatedly? Section 1.1 briefly reviews the status of the efficient markets paradigm.In section 1.2, we consider a typology of markets that sheds light on the conditions under which the model of efficient markets may have to give way to behavioral explanations.In section 1.3,we discuss four behavioral hypotheses,which are subsequently used to explain a range of selected financial market flows. 1.1 The efficient markets paradigm Financial economists assess the efficiency of a market in terms of its ability to incorporate relevant information,rather than to minimize transactions costs or to attain social welfare desiderata such as Pareto efficiency.More exactly,a market is said to be efficient with respect to an information set if no participant with access to that information can make systematic excess retums.Note that this definition does not require that prices be a sufficient statistic for the information.For example,individuals may need to spend resources to avail themselves of the information3 impounded in prices in order to form optimal portfolios,even if information acquisition costs can not be justified by the likelihood of discovering mispriced assets.9 An efficient market implies that there should be no arbitrage opportunities;that it,it should not be possible to make a sure profit with a zero-risk zero-investment strategy.This seemingly trifling condition led to interesting and empirically successful pricing relations for TThebeuristicssig probability onhe basis of simirityignoring relvann as hase rates (prior unconditional prohahilities)and sample sizes. SIf individuals can kam others'information by observing prices,that information will have a public goods aspect: too little of it will be privately provided.If securities may be mispriced,on the other hand,there is a competitive advantage in securing information not possessed by others:too much expenditures on information may be consequence(Hirshleifer,1971). While simple models of financialqugenerniveoimorfolio (the"etportfolio in the context of the Capital Asset Pricing Model.for instance).recent models that accommodate differences between individual investors in the breadth of knowledge about assets imply optimal portfolios that must be individually tailored see Merton (1987a)

4- derivative securities such as options and collateralized mortgage obligations,for which arbitrage strategies entail complex dynamic trading.The celebrated Black-Scholes option pricing formula spawned a large derivative asset-pricing industry,within which the lines between academia and practice have blurred.No-arbitrage conditions pin down relative prices (e.g.,how the price of a call option on IBM shares should be linked to the share price). Whether the price level of the share itself is correct is more difficult to establish,since a model of equilibrium pricing must be invoked.Black(1986)-a pioneer of the efficient markets model-observes that the empirical tests to date may not reject the market efficiency hypothesis even if the price levels are off by a factor of 100%. Of course,as Fama(1990)notes,"The market efficiency hypothesis is an extreme null hypothesis,a point on a continuum,and so almost surely false.The interesting task is...to measure the extent to which behavior of returns departs from its predictions."After nearly four decades of intensive empirical investigation of investment market prices,the gross evidence generally supports the hypothesis-see recent surveys in Merton(1987b)and Fama (1990).The evidence from firm behavior and the market for corporate control is more controversial:witness the raging debates about whether junk bonds or hostile acquisitions promote efficiency,and whether associated transaction prices are ex-ante appropriate.We know that some cities fail to discount for time in choosing capital projects.And there are myriad stories of firms making uncritical and incorrect use of weighted average cost-of-capital figures in their capital budgeting. The power of the market efficiency principle provoked ingenious efforts to explain anomalies.These efforts yielded insights in agency theory,asymmetric information equilibria, signaling,and game theory.Clearly,the field gained by maintaining an intuitively wise organizing principle as a null hypothesis.Compare the similar success of the genetic-fitness paradigm for evolutionary modeling,which spawned a vast literature on evolutionary psychology (with ripple effects in philosophy and sociology). After the early battles in academia,the efficiency benchmark has become a valuable null hypothesis for organizing lessons and studies about financial behavior.Models that purport to violate this principle have to be explicitly articulated and subjected to rigorous testing. Unfortunately,many studies placed such a large prior probability on the market efficiency hypothesis that falsifying findings were almost precluded.For example,the academic consensus about exchange rates is that they are uncorrelated and unpredictable.Nevertheless sophisticated speculators and technical advisors claim to consistently observe and take Te Dawkins (9)onhe genetic fitess principle which shres overoes with theriosfishess principle in neoclassical economies and methodological individualism in sociology.Dupre(1987)has edited a more recent collection of related essays

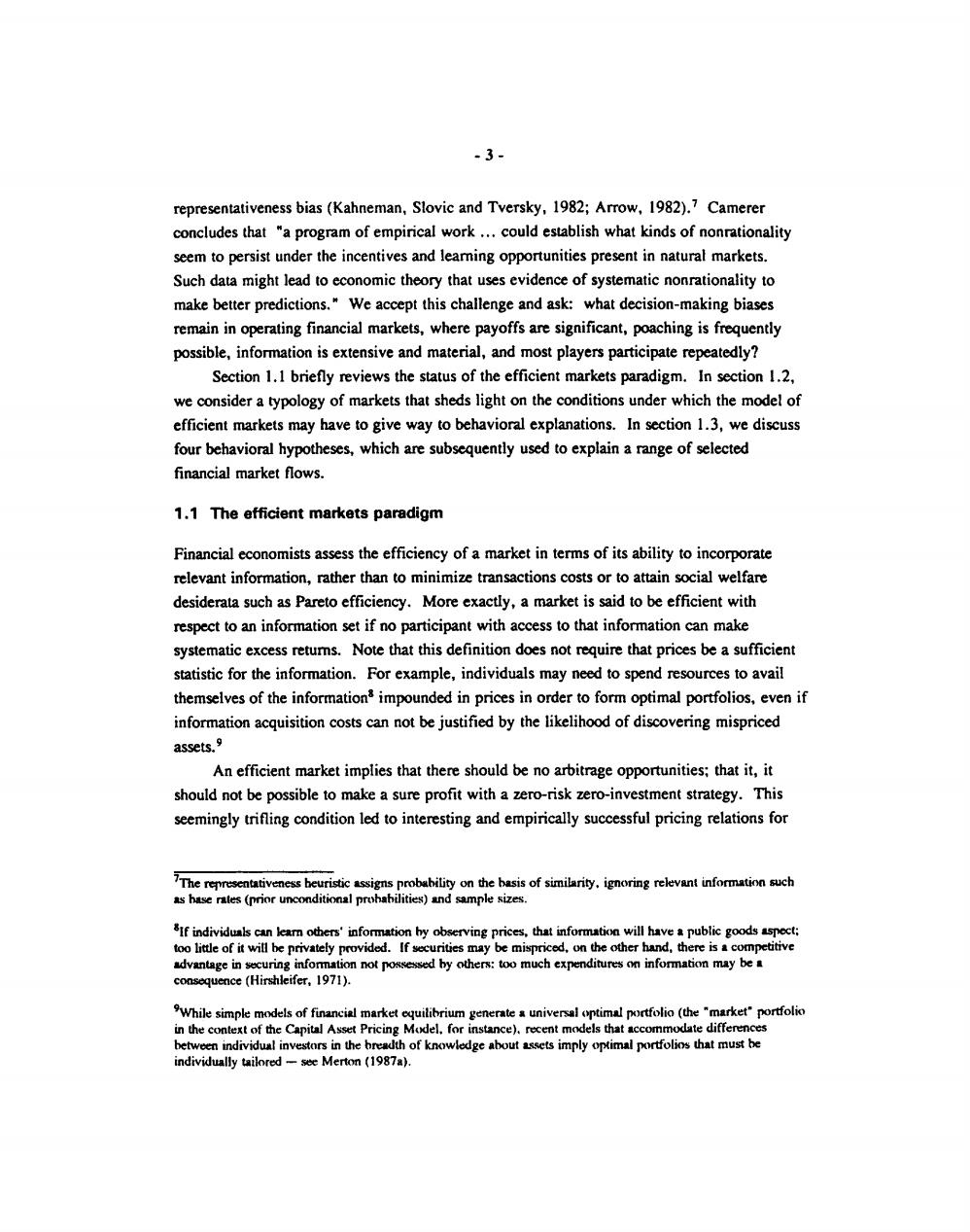

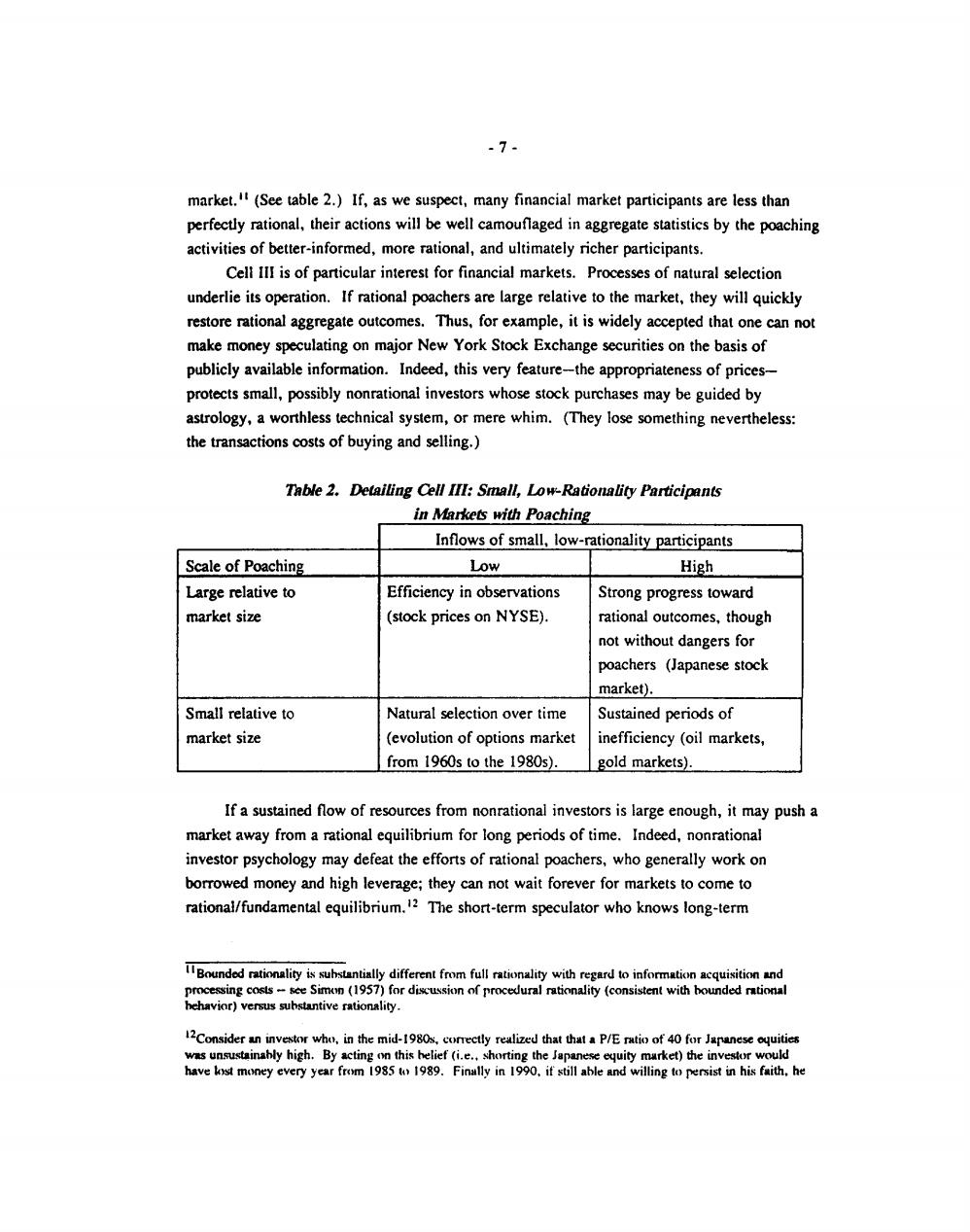

-5. advantage of subtle nonlinear patterns-see Goodman(1982),Engel and Hamilton(1990), and Bilson(1990).Finally,the problem of joint hypothesis testing has led to some tests that have very low power to reject plausible deviations from market efficiency.A priori faith in the power of no-arbitrage has probably clouded the common sense recognition that human errors might persist or even compound rather than cancel each other. Nonetheless the efficient markets hypothesis provides a natural benchmark,and thus financial markets are a promising arena in which to investigate deviations from rational behavior.The research is facilitated by the facts that financial markets are liquid,and individual motivations are relatively straightforward,in accord with wealth-maximizing hypotheses (possibly modified by risk aversion).Moreover,the operation of these markets is thoroughly recorded,with rich price and volume data readily available. 1.2 Typology of markets The nonrational behaviors of individuals,although well documented,may not be apparent at the market level because many financial markets offer poaching potential(that is,players can take advantage of poor decisions made by others).More generally,aggregate social outcomes reflect both prevailing levels of individual rationality and opportunities for poaching,as table 1 shows schematically.Poachability will play an important role in determining which macro outcomes we study to draw inferences about levels of individual rationality. Table I.Models for Outcomes of Social Interactions: Poachability and Rationality Poachability/Arbitrage Potential Individual High Low Rationality Substantial/Full I.Efficient markets. II.Deviations due to sluggish information flow (e.g., mispriced open-end mutual funds). Bounded/Low III.Continual movement IV.Gross behavioral (behavioral to restore efficiency (see outcomes (e.g.,marriages- anomalies observed) Table 2). poor fits frequent;bargains -beneficial deals not struck; finance-inadequate personal savings)

-6- When individuals are rational and there are many opportunities for arbitrage,we expect the efficient markets paradigm to be dominant(cell I in Table 1).At the other extreme(cell IV)behavioral models should provide a better description of aggregate outcomes.For example,because of long lead times,poor institutional planning,and individual failures of foresight,we observe cycles of excess-and under-production of teachers.The situation is akin to the corn-hog cycle familiar to economists,with the crucial difference that in the agricultural arena,futures markets facilitate an efficient smoothing of suboptimal swings.Many of the least happy areas of human activity fall into cell IV.The mischosen marriage partner or poorly fitting job is prototypical.So too are patterns of preferences-such as excessive attention to one's relative as to opposed to one's absolute position-that are inconsistent with what we normally assume for rationality.For example,the inadequate levels of personal savings in the United States may be due to excessive competition in consumption levels,as a means to signal one's status(Frank,1985). Cell IV is also the sad domain where many an advantageous exchange is not made, perhaps because of greed or desire to do better than the other party,or merely because of the intractability of bargaining.One of the undersung virtues of the market is that by putting many participants on each side of bargaining situations,it defines the way the surplus from striking a deal should be divided,and thereby avoids costly impasses.Thus market outcomes establish a price for carrots;as buyers we accept it when it is below our reservation price,or else move on to the rutabaga stand,without wasting our time trying to cajole the carrot seller into lowering his price. It is in cells II and III that a merger of behavioral considerations and economic market analysis can be most fruitful.In situations that are characterized by low poachability but in which rational choice conditions predominate (cell II),we expect economic paradigms to succeed,albeit with behavioral residues leading to periodic observable anomalies(see section 2).For example,if most drivers are rational,we would expect them to choose the most economical route for commuting.This assumption is fruitfully invoked in transport models even though rational commuter A can not derive any advantage for herself from(poach upon) misguided B whose "shortcut"adds 10 minutes to his trip.Even if individuals are fully rational,they may not possess all relevant information,and those with superior information may not be able to capitalize upon it.Thus,open-end mutual funds can sell at inappropriate prices,and firms with market power may produce inappropriate products.Rationality,by itself,provides little guidance as to what outcomes are appropriate.If it did,the participants would immediately gravitate to such outcomes. The expected patters for situations corresponding to cell IlI depend crucially on the dynamics of the situation and the magnitude of flows that nonrational participants bring to the

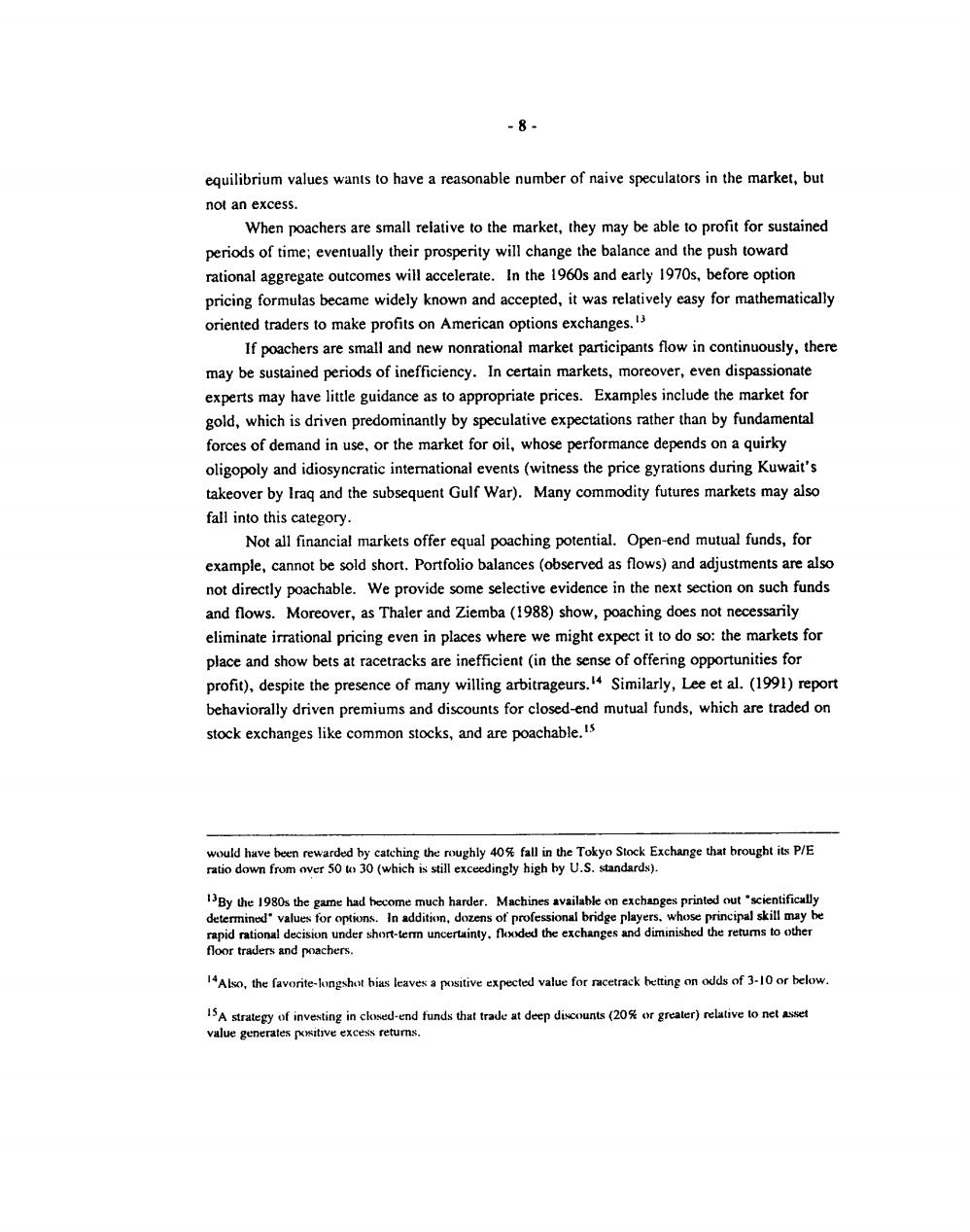

-7- market.(See table 2.)If,as we suspect,many financial market participants are less than perfectly rational,their actions will be well camouflaged in aggregate statistics by the poaching activities of better-informed,more rational,and ultimately richer participants. Cell III is of particular interest for financial markets.Processes of natural selection underlie its operation.If rational poachers are large relative to the market,they will quickly restore rational aggregate outcomes.Thus,for example,it is widely accepted that one can not make money speculating on major New York Stock Exchange securities on the basis of publicly available information.Indeed,this very feature-the appropriateness of prices- protects small,possibly nonrational investors whose stock purchases may be guided by astrology,a worthless technical system,or mere whim.(They lose something nevertheless: the transactions costs of buying and selling. Table 2.Detailing Cell III:Small,Low-Rationality Participants in Markets with Poaching Inflows of small,low-rationality participants Scale of Poaching Low High Large relative to Efficiency in observations Strong progress toward market size (stock prices on NYSE). rational outcomes,though not without dangers for poachers (Japanese stock market). Small relative to Natural selection over time Sustained periods of market size (evolution of options market inefficiency (oil markets, from 1960s to the 1980s). gold markets). If a sustained flow of resources from nonrational investors is large enough,it may push a market away from a rational equilibrium for long periods of time.Indeed,nonrational investor psychology may defeat the efforts of rational poachers,who generally work on borrowed money and high leverage;they can not wait forever for markets to come to rational/fundamental equilibrium.12 The short-term speculator who knows long-term Bounded rationlity is sustntilly different from full rationity withetoinformtion acqsition nd processing costs-see Simon (1957)for discussion of procedural rationality (consistent with bounded rational hehavior)versus suhstantive rationality. 12Consider a investor who.in the mid-1980s,comrectly realized that thatP/E ratio of 40 forJaesequities was unsustainably high.By acting on this helief(i.e..shorting the Japanese equity market)the investor would have kst money every year from 19851989.Finally in 1990.if still able and willing to persist in his faith,he

-8- equilibrium values wants to have a reasonable number of naive speculators in the market,but not an excess. When poachers are small relative to the market,they may be able to profit for sustained periods of time;eventually their prosperity will change the balance and the push toward rational aggregate outcomes will accelerate.In the 1960s and early 1970s,before option pricing formulas became widely known and accepted,it was relatively easy for mathematically oriented traders to make profits on American options exchanges.3 If poachers are small and new nonrational market participants flow in continuously,there may be sustained periods of inefficiency.In certain markets,moreover,even dispassionate experts may have little guidance as to appropriate prices.Examples include the market for gold,which is driven predominantly by speculative expectations rather than by fundamental forces of demand in use,or the market for oil,whose performance depends on a quirky oligopoly and idiosyncratic interational events(witness the price gyrations during Kuwait's takeover by Iraq and the subsequent Gulf War).Many commodity futures markets may also fall into this category. Not all financial markets offer equal poaching potential.Open-end mutual funds,for example,cannot be sold short.Portfolio balances (observed as flows)and adjustments are also not directly poachable.We provide some selective evidence in the next section on such funds and flows.Moreover,as Thaler and Ziemba (1988)show,poaching does not necessarily eliminate irrational pricing even in places where we might expect it to do so:the markets for place and show bets at racetracks are inefficient(in the sense of offering opportunities for profit),despite the presence of many willing arbitrageurs.4 Similarly,Lee et al.(1991)report behaviorally driven premiums and discounts for closed-end mutual funds,which are traded on stock exchanges like common stocks,and are poachable.ts would have been rewarded by catching the roughly 40%fall in the Tokyo Stock Exchange that brought its P/E ratio down from over 50 to 30(which is still exceedingly high by U.S.standards). iBy the 1980s the game had become much harder.Machines available on exchanges printed out"scientifically determined"values for options.In addition,dozens of professional bridge players.whose principal skill may be rapid rational decision under short-term uncertainty.flooded the exchanges and diminished the retums to other floor traders and poachers. 14Also,the favorite-longshot bias leaves a positive expected value for racetrack betting on odds of 3-10 or below. 15A strategy of investing in closed-end funds that trade at deep discounts(20or greater)relative to net asset value generates positive excess returns