THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE.VOL.LIII,NO.6.DECEMBER 1998 Investor Psychology and Security Market Under-and Overreactions KENT DANIEL,DAVID HIRSHLEIFER,and AVANIDHAR SUBRAHMANYAM ABSTRACT We propose a theory of securities market under-and overreactions based on two well-known psychological biases:investor overconfidence about the precision of private information;and biased self-attribution,which causes asymmetric shifts in investors'confidence as a function of their investment outcomes.We show that overconfidence implies negative long-lag autocorrelations,excess volatility,and, when managerial actions are correlated with stock mispricing,public-event-based return predictability.Biased self-attribution adds positive short-lag autocorrela- tions ("momentum"),short-run earnings "drift,"but negative correlation between future returns and long-term past stock market and accounting performance.The theory also offers several untested implications and implications for corporate fi- nancial policy. IN RECENT YEARS A BODY OF evidence on security returns has presented a sharp challenge to the traditional view that securities are rationally priced to re- flect all publicly available information.Some of the more pervasive anoma- lies can be classified as follows (Appendix A cites the relevant literature): 1.Event-based return predictability (public-event-date average stock re- turns of the same sign as average subsequent long-run abnormal per- formance) 2.Short-term momentum (positive short-term autocorrelation of stock re- turns,for individual stocks and the market as a whole) *Daniel is at Northwestern University and NBER,Hirshleifer is at the University of Mich- igan,Ann Arbor,and Subrahmanyam is at the University of California at Los Angeles.We thank two anonymous referees,the editor (Rene Stulz),Michael Brennan,Steve Buser,Werner DeBondt,Eugene Fama,Simon Gervais,Robert Jones,Blake LeBaron,Tim Opler,Canice Pren- dergast,Andrei Shleifer,Matt Spiegel,Siew Hong Teoh,and Sheridan Titman for helpful com- ments and discussions,Robert Noah for excellent research assistance,and participants in the National Bureau of Economic Research 1996 Asset Pricing Meeting,and 1997 Behavioral Fi- nance Meeting,the 1997 Western Finance Association Meetings,the 1997 University of Chicago Economics of Uncertainty Workshop,and finance workshops at the Securities and Exchange Commission and the following universities:University of California at Berkeley,University of California at Los Angeles,Columbia University,University of Florida,University of Houston, University of Michigan,London Business School,London School of Economics,Northwestern University,Ohio State University,Stanford University,and Washington University at St.Louis for helpful comments.Hirshleifer thanks the Nippon Telephone and Telegraph Program of Asian Finance and Economics for financial support. 1839

1840 The Journal of Finance 3.Long-term reversal(negative autocorrelation of short-term returns sep arated by long lags,or "overreaction") 4.High volatility of asset prices relative to fundamentals 5.Short-run post-earnings announcement stock price "drift"in the direc- tion indicated by the earnings surprise,but abnormal stock price per- formance in the opposite direction of long-term earnings changes. There remains disagreement over the interpretation of the above evidence of predictability.One possibility is that these anomalies are chance devia- tions to be expected under market efficiency (Fama (1998)).We believe the evidence does not accord with this viewpoint because some of the return patterns are strong and regular.The size,book-to-market,and momentum effects are present both internationally and in different time periods.Also, the pattern mentioned in (1)above obtains for the great majority of event studies. Alternatively,these patterns could represent variations in rational risk premia.However,based on the high Sharpe ratios (relative to the market) apparently achievable with simple trading strategies (MacKinlay (1995)), any asset pricing model consistent with these patterns would have to have extremely variable marginal utility across states.Campbell and Cochrane (1994)find that a utility function with extreme habit persistence is required to explain the predictable variation in market returns.To be consistent with cross-sectional predictability findings(e.g.,on size,book-to-market,and mo- mentum),a model would presumably require even more extreme variation in marginal utilities.Also,the model would require that marginal utilities covary strongly with the returns on the size,book-to-market,and momen- tum portfolios.But when the data are examined,no such correlation is ob- vious.Given this evidence,it seems reasonable to consider explanations for the observed return patterns based on imperfect rationality. Moreover,there are important corporate financing and payout patterns that seem potentially related to market anomalies.Firms tend to issue eq- uity (rather than debt)after rises in market value and when the firm or industry book-to-market ratio is low.There are industry-specific financing and repurchase booms,perhaps designed to exploit industry-level mispric- ings.Transactions such as takeovers that often rely on securities financing are also prone to industry booms and quiet periods. Although it is not obvious how the empirical securities market phenomena can be captured plausibly in a model based on perfect investor rationality,no psychological ("behavioral")theory for these phenomena has won general acceptance.Some aspects of the patterns seem contradictory,such as appar- ent market underreaction in some contexts and overreaction in others.Ex- planations have been offered for particular anomalies,but we have lacked both an integrated theory to explain these phenomena and out-of-sample empirical implications to test proposed explanations. A general criticism often raised by economists against psychological theo- ries is that,in a given economic setting,the universe of conceivable irratio- nal behavior patterns is essentially unrestricted.Thus,it is sometimes claimed

Investor Psychology and Market Reactions 1841 that allowing for irrationality opens a Pandora's box of ad hoc stories that will have little out-of-sample predictive power.However,DeBondt and Tha- ler(1995)argue that a good psychological finance theory will be grounded on psychological evidence about how people actually behave.We concur,and also believe that such a theory should allow for the rational side of investor decisions.To deserve consideration a theory should be parsimonious,explain a range of anomalous patterns in different contexts,and generate new em- pirical implications.The goal of this paper is to develop such a theory of security markets. Our theory is based on investor overconfidence,and variations in confi- dence arising from biased self-attribution.The premise of investor overcon- fidence is derived from a large body of evidence from cognitive psychological experiments and surveys (summarized in Section 1)which shows that indi- viduals overestimate their own abilities in various contexts. In financial markets,analysts and investors generate information for trad- ing through means,such as interviewing management,verifying rumors, and analyzing financial statements,that can be executed with varying de- grees of skill.If an investor overestimates his ability to generate informa- tion,or to identify the significance of existing data that others neglect,he will underestimate his forecast errors.If he is more overconfident about signals or assessments with which he has greater personal involvement,he will tend to be overconfident about the information he has generated but not about public signals.Thus,we define an overconfident investor as one who overestimates the precision of his private information signal,but not of in- formation signals publicly received by all. We find that the overconfident-informed overweight the private signal rel- ative to the prior,causing the stock price to overreact.When noisy public information signals arrive,the inefficient deviation of the price is partially corrected,on average.On subsequent dates,as more public information ar- rives,the price,on average,moves still closer to the full-information value. Thus,a central theme of this paper is that stock prices overreact to private information signals and underreact to public signals.We show that this overreaction-correction pattern is consistent with long-run negative autocor- relation in stock returns,with unconditional excess volatility (in excess of what would obtain with fully rational investors),and with further implica- tions for volatility conditional on the type of signal. The market's tendency to over-or underreact to different types of infor- mation allows us to address the remarkable pattern that the average an- nouncement date returns in virtually all event studies are of the same sign as the average post-event abnormal returns.Suppose that the market ob- serves a public action taken by an informed party such as a firm at least partly in response to market mispricing.For example,a rationally managed firm may tend to buy back more of its stock when managers believe their stock is undervalued by the market.In such cases,the corporate event will reflect the managers'belief about the market valuation error,and will there- fore predict future abnormal returns.In particular,repurchases,reflecting undervaluation,will predict positive abnormal returns,and equity offerings

1842 The Journal of Finance will predict the opposite.More generally,actions taken by any informed party (such as a manager or analyst)in response to mispricing will predict future returns.Consistent with this implication,many events studied in the em- pirical literature can reasonably be viewed as being responsive to mispric- ing,and have the abnormal return pattern discussed above.Section II.B.4 offers several additional implications about the occurrence of and price pat- terns around corporate events and for corporate policy that are either un- tested or have been confirmed only on a few specific events. The empirical psychology literature reports not just overconfidence,but that as individuals observe the outcomes of their actions,they update their confidence in their own ability in a biased manner.According to attribution theory (Bem (1965)),individuals too strongly attribute events that confirm the validity of their actions to high ability,and events that disconfirm the action to external noise or sabotage.(This relates to the notion of cognitive dissonance,in which individuals internally suppress information that con- flicts with past choices.) If an investor trades based on a private signal,we say that a later public sig- nal confirms the trade if it has the same sign(good news arrives after a buy, or bad news after a sell).We assume that when an investor receives confirm- ing public information,his confidence rises,but disconfirming information causes confidence to fall only modestly,if at all.Thus,if an individual begins with un- biased beliefs about his ability,new public signals on average are viewed as confirming the validity of his private signal.This suggests that public infor- mation can trigger further overreaction to a preceding private signal.We show that such continuing overreaction causes momentum in security prices,but that such momentum is eventually reversed as further public information gradu- ally draws the price back toward fundamentals.Thus,biased self-attribution implies short-run momentum and long-term reversals. The dynamic analysis based on biased self-attribution can also lead to a lag-dependent response to corporate events.Cash flow or earnings surprises at first tend to reinforce confidence,causing a same-direction average stock price trend.Later reversal of overreaction can lead to an opposing stock price trend.Thus,the analysis is consistent with both short term post- announcement stock price trends in the same direction as earnings sur- prises and later reversals. In our model,investors are quasi-rational in that they are Bayesian opti- mizers except for their overassessment of valid private information,and their biased updating of this precision.A frequent objection to models that explain price anomalies as market inefficiencies is that fully rational investors should be able to profit by trading against the mispricing.If wealth flows from quasi-rational to smart traders,eventually the smart traders may dominate price-setting.However,for several reasons,we do not find this argument to be compelling,as discussed in the conclusion. Several other papers model overconfidence in various contexts.De Long et al.(1991)examine the profits of traders who underestimate risk when prices are exogenous.Hirshleifer,Subrahmanyam,and Titman(1994)exam- ine how analyst/traders who overestimate the probability that they receive

Investor Psychology and Market Reactions 1843 information before others will tend to herd in selecting stocks to study.Kyle and Wang (1997),Odean (1998),and Wang (1998)provide specifications of overconfidence as overestimation of information precision,but do not distin- guish between private and public signals in this regard(see also Caballe and Sakovics (1996)).Odean (1998)examines overconfidence about,and conse- quent overreaction to,a private signal,which results in excess volatility and negative return autocorrelation.Because our model assumes that investors are overconfident only about private signals,we obtain underreaction as well as overreaction effects.Furthermore,because we consider time-varying confidence,there is continuing overreaction to private signals over time. Thus,in contrast to Odean,we find forces toward positive as well as nega- tive autocorrelation;and we argue that overconfidence can decrease volatil- ity around public news events.1 Daniel,Hirshleifer,and Subrahmanyam (1998)show that our specifica- tion of overconfidence can help explain several empirical puzzles regarding cross-sectional patterns of security return predictability and investor behav- ior.These puzzles include the ability of price-based measures(dividend yield, earnings/price,book-to-market,and firm market value)to predict future stock returns,possible domination of B as a predictor of returns by price- based variables,and differences in the relative ability of different price- based measures to predict returns. A few other recent studies have addressed both overreaction and under- reaction in an integrated fashion.Shefrin(1997)discusses how base rate underweighting can shed light on the anomalous behavior of implied vola- tilities in options markets.In a contemporaneous paper,Barberis,Shleifer, and Vishny (1998)offer an explanation for under-and overreactions based on a learning model in which actual earnings follow a random walk,but individuals believe that earnings either follow a steady growth trend or are mean-reverting.Because their focus is on learning about the time-series process of a performance measure such as earnings,they do not address the sporadic events examined in most event studies.In another recent paper, Hong and Stein (1998)examine a setting where under-and overreactions arise from the interaction of momentum traders and news watchers.Mo- mentum traders make partial use of the information contained in recent price trends and ignore fundamental news.News watchers rationally use fundamental news but ignore prices.Our paper differs in focusing on psychological evidence as a basis for assumptions about investor behavior. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.Section I describes psychological evidence of overconfidence and self-attribution bias.Section II develops the basic model of overconfidence,and here we describe the eco- nomic setting and define overconfidence.We analyze the equilibrium to de- rive implications about stock price reactions to public versus private news, short-term versus long-term autocorrelations,and volatility.Section III ex- 1A recent revision of Odean's paper offers a modified model that allows for underreaction. This is developed in a static setting with no public signals,and therefore does not address issues such as short-term versus long-term return autocorrelations,and event-study anomalies

1844 The Journal of Finance amines time variation in overconfidence to derive implications about the signs of short-term versus long-term return autocorrelations.Section IV con- cludes by summarizing our findings,relating our analysis to the literature on exogenous noise trading,and discussing issues related to the survival of overconfident traders in financial markets. I.Overconfidence and Biased Self-Attribution Our theory relies on two psychological regularities:overconfidence and attribution bias.In their summary of the microfoundations of behavioral finance,DeBondt and Thaler (1995)state that "perhaps the most robust finding in the psychology of judgment is that people are overconfident."Ev- idence of overconfidence has been found in several contexts.Examples in- clude psychologists,physicians and nurses,engineers,attorneys,negotiators, entrepreneurs,managers,investment bankers,and market professionals such as security analysts and economic forecasters.2Further,some evidence sug- gests that experts tend to be more overconfident than relatively inexperi- enced individuals (Griffin and Tversky (1992)).Psychological evidence also indicates that overconfidence is more severe for diffuse tasks (e.g.,making diagnoses of illnesses),which require judgment,than for mechanical tasks (e.g.,solving arithmetic problems);and more severe for tasks with delayed feedback as opposed to tasks that provide immediate and conclusive outcome feedback (see Einhorn (1980)).Fundamental valuation of securities (fore- casting long-term cash flows)requires judgment about open-ended issues, and feedback is noisy and deferred.We therefore focus on the implications of overconfidence for financial markets.3 Our theory assumes that investors view themselves as more able to value securities than they actually are,so that they underestimate their forecast error variance.This is consistent with evidence that people overestimate their own abilities,and perceive them- selves more favorably than they are viewed by others. Several experimental studies find that individuals underestimate their error variance in making predictions,and overweight their own forecasts relative to those of others.5 The second aspect of our theory is biased self-attribution:The confidence of the investor in our model grows when public information is in agreement with his information,but it does not fall commensurately when public information 2 See respectively:Oskamp (1965);Christensen-Szalanski and Bushyhead,(1981),Bau- mann,Deber,Thompson,(1991);(Kidd (1970);Wagenaar and Keren(1986);Neale and Bazer- man (1990);Cooper,Woo,and Dunkelberg (1988);Russo and Schoemaker (1992);Vonholstein (1972);Ahlers and Lakonishok (1983),Elton,Gruber,and Gultekin (1984),Froot and Frankel (1989),DeBondt and Thaler (1990),DeBondt (1991).See Odean(1998)for a good summary of empirical research on overconfidence. Odean (1998)(Sec.II.D)also makes a good argument for why overconfidence should dom- inate in financial markets.Also,Bernardo and Welch(1998)offer an evolutionary explanation for why individuals should be overconfident. 4 Greenwald (1980),Svenson (1981),Cooper et al.1988,and Taylor and Brown (1988). 5 See Alpert and Raiffa(1982),Fischhoff,Slovic,and Lichtenstein(1977),Batchelor and Dua (1992),and the discussions of Lichtenstein,Fischhoff,and Phillips(1982)and Yates(1990)

Investor Psychology and Market Reactions 1845 contradicts his private information.The psychological evidence indicates that people tend to credit themselves for past success,and blame external factors for failure (Fischhoff(1982),Langer and Roth(1975),Miller and Ross(1975), Taylor and Brown(1988)).As Langer and Roth(1975)put it,"Heads I win,tails it's chance";see also the discussion of De Long et al.(1991). II.The Basic Model:Constant Confidence This section develops the model with static confidence.Section III consid- ers time-varying confidence.Each member of a continuous mass of agents is overconfident in the sense that if he receives a signal,he overestimates its precision.We refer to those who receive the signal as the informed,I,and those who do not as the uninformed,U.For tractability,we assume that the informed are risk neutral and that the uninformed are risk averse. Each individual is endowed with a basket containing security shares,and a risk-free numeraire that is a claim to one unit of terminal-period wealth There are four dates.At date 0,individuals begin with their endowments and identical prior beliefs,and trade solely for optimal risk-transfer pur- poses.At date 1,I receives a common noisy private signal about underlying security value and trades with U.At date 2,a noisy public signal arrives, and further trade occurs.At date 3,conclusive public information arrives, the security pays a liquidating dividend,and consumption occurs.All ran- dom variables are independent and normally distributed. The risky security generates a terminal value of 0,which is assumed to be normally distributed with mean and variance o.For most of the paper we set 0=0 without loss of generality.The private information signal received by I at date 1 is S1=0+∈, (1) where e~N(0,2)(so the signal precision is 1/02).U correctly assesses the error variance,but I underestimates it to be o<o2.The differing beliefs about the noise variance are common knowledge to all.?Similarly,the date 2 public signal is S2=0+7, (2) 6 Some previous models with common private signals include Grossman and Stiglitz(1980), Admati and Pfleiderer(1988),and Hirshleifer et al.(1994).If some analysts and investors use the same information sources to assess security values,and interpret them in similar ways,the error terms in their signals will be correlated.For simplicity,we assume this correlation is unity;how- ever,similar results would obtain under imperfect(but nonzero)correlation in signal noise terms. 7 It is not crucial for the analysis that the uninformed correctly assesses the private signal variance,only that he does not underestimate it as much as the informed does.Also,because U does not possess a signal to be overconfident about,he could alternatively be interpreted as a fully rational trader who trades to exploit market mispricing.Furthermore,most of the results will obtain even if investors are symmetrical both in their overconfidence and their signals. Results similar to those we derive would apply in a setting where identical overconfident in- dividuals receive correlated private signals

1846 The Journal of Finance where the noise term n-N(0,p)is independent of 0 and e.Its variance op is correctly estimated by all investors. Our simplifying assumption that all private information precedes all pub- lic information is not needed for the model's implications.It is essential that at least some noisy public information arrives after a private signal.The model's implications stand if,more realistically,additional public informa- tion precedes or is contemporaneous with the private signal. The formal role of the uninformed in this paper is minimal because prices are set by the risk-neutral informed traders.The rationale for the assump- tion of overconfidence is that the investor has a personal attachment to his own signal.This implies some other set of investors who do not receive the same signal.Also,similar results will hold if both groups of investors are risk averse,so that both groups influence price.We have verified this ana- lytically in a simplified version of the model.So long as the uninformed are not risk-neutral price setters,the overconfident informed will push price away from fully rational values in the direction described here. A.Equilibrium Prices and Trades Because the informed traders are risk neutral,prices at each date satisfy P1=Ec[00+e] (3) P2=Ec[00+∈,0+n], (4) where the subscript C denotes the fact that the expectation operator is cal- culated based on the informed traders'confident beliefs.Trivially,Pa=6.By standard properties of normal variables (Anderson (1984),Chap.2), P1= 02 (0+e) (5) 子+8 B=io哈+哈g+听吃。ui呢 -0+ De+、 D, (6) D where D≡o(o呢+o)+o尼c2 B.Implications for Price Behavior This section examines the implications of static confidence for over-and underreactions to information and empirical securities returns patterns.Sub- section B.1 examines price reactions to public and private information,sub- section B.2 examines the implications for price-change autocorrelations,and subsection B.3 examines implications for event-studies.Subsection B.4 dis- cusses some as-yet-untested empirical implications of the model

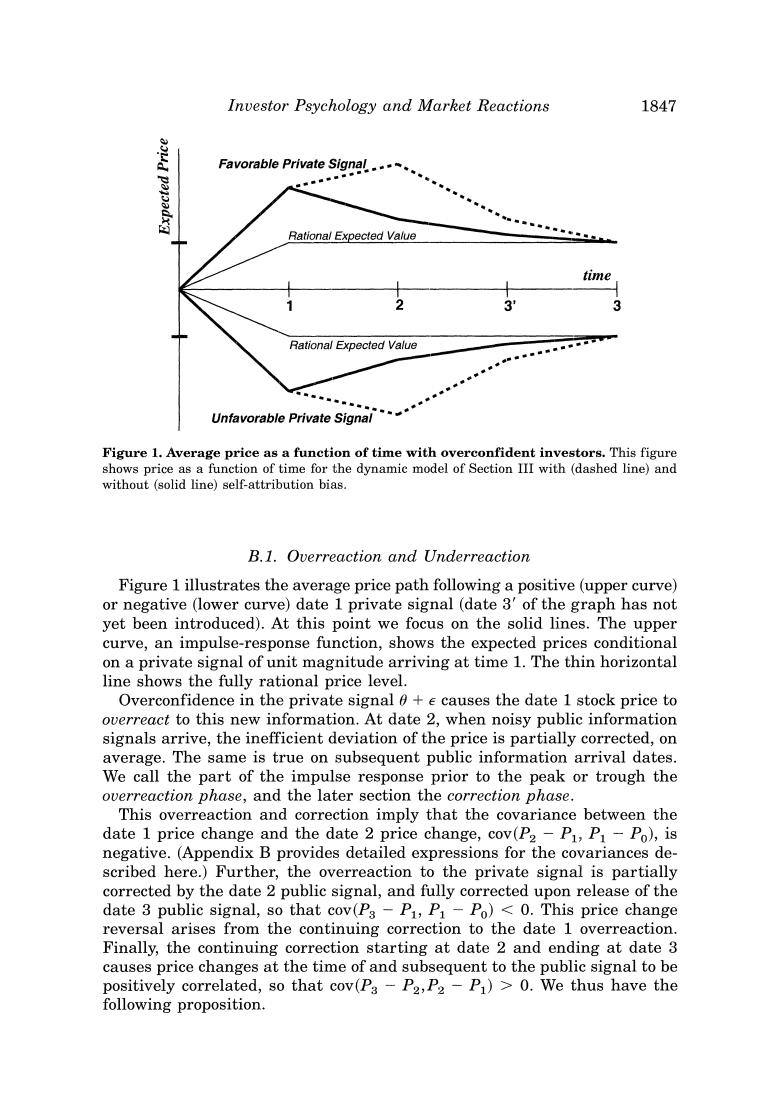

Investor Psychology and Market Reactions 1847 Favorable Private Signal Rational Expected Value time Rational Expected Value Unfavorable Private Signal Figure 1.Average price as a function of time with overconfident investors.This figure shows price as a function of time for the dynamic model of Section III with(dashed line)and without (solid line)self-attribution bias. B.1.Overreaction and Underreaction Figure 1 illustrates the average price path following a positive(upper curve) or negative (lower curve)date 1 private signal(date 3'of the graph has not yet been introduced).At this point we focus on the solid lines.The upper curve,an impulse-response function,shows the expected prices conditional on a private signal of unit magnitude arriving at time 1.The thin horizontal line shows the fully rational price level. Overconfidence in the private signal +e causes the date 1 stock price to overreact to this new information.At date 2,when noisy public information signals arrive,the inefficient deviation of the price is partially corrected,on average.The same is true on subsequent public information arrival dates. We call the part of the impulse response prior to the peak or trough the overreaction phase,and the later section the correction phase. This overreaction and correction imply that the covariance between the date 1 price change and the date 2 price change,cov(P2-P1,P1-Po),is negative.(Appendix B provides detailed expressions for the covariances de- scribed here.)Further,the overreaction to the private signal is partially corrected by the date 2 public signal,and fully corrected upon release of the date 3 public signal,so that cov(Ps-P1,P1-Po)0.We thus have the following proposition

1848 The Journal of Finance PROPOSITION 1:If investors are overconfident,then: 1.Price moves resulting from private information arrival are on average partially reversed in the long run. 2.Price moves in reaction to the arrival of public information are posi- tively correlated with later price changes. The pattern of correlations described in Proposition 1 is potentially testable by examining whether long-run reversals following days with public news events are smaller than reversals on days without such events.The price behavior around public announcements has implications for corporate event studies (see Subsection B.3). B.2.Unconditional Serial Correlations and Volatility Return autocorrelations in well-known studies of momentum and reversal are calculated without conditioning on the arrival of a public information signal.To calculate a return autocorrelation that does not condition on whether private versus public information has arrived,consider an experiment where the econometrician randomly picks consecutive dates for price changes(dates 1 and 2,versus dates 2 and 3).The date 2 and 3 price changes are positively correlated,but the date 1 and 2 price changes are negatively correlated. Suppose that the econometrician is equally likely to pick either pair of con- secutive dates.Then the overall autocorrelation is negative. PROPOSITION 2:If investors are overconfident,price changes are uncondition- ally negatively autocorrelated at both short and long lags. Thus,the constant-confidence model accords with long-run reversals(nega- tive long-lag autocorrelations)but not with short-term momentum(positive short-lag autocorrelation).However,the short-lag autocorrelation will be pos- itive in a setting where the extremum in the impulse response function is sufficiently smooth,because the negative autocovariance of price changes surrounding a smooth extremum will be low in absolute terms.Such a set- ting,based on biased self-attribution and outcome-dependent confidence,is considered in Section III. Overconfidence causes wider swings at date 1 away from fundamentals, thereby causing excess price volatility around private signals(var(PI-Po)), as in Odean(1998).Greater overconfidence also causes relative underweight- ing of the public signal,which tends to reduce date 2 variance.However,the wide date 1 swings create a greater need for corrective price moves at dates 2 and 3,so that greater overconfidence can either decrease or increase the volatility around public signals(var(P2-P)).(Explicit expressions for the variances of this section are contained in Appendix B.)Consider again an econometrician who does not condition on the occurrence of private or public news arrival.When calculating price change variances he gives equal weight to price changes P1-Po,P2-P1,and Ps-P2.The unconditional volatility