Perceived Causes of Marriage Breakdown and Conditions of Life AILSA BURNS Macquarie University A large number of structural and attitudinal variables have been regularly found to be asso- ciated with marital dissolution.Fourteen such variables were located and related to the causes of breakdown as perceived by 335 divorced and separated men and women.Five perceived causes were associated with perceptions of the marriage as beginning to break down at particular time periods,but not with duration of marriage.Sex of respondent, SES,respondent's and spouse's religion,age at marriage,marital status (divorced or sepa- rated),parity of marriage,parental approval,stability of parents'and in-laws'marriages, length of premarital acquaintance,marriage duration and number of children,and stan- dard of living since separation all were associated with one or more of the reasons given by respondents for the marriage breakdown.An exploratory factor analysis gave a 7-factor solution supporting the notion that different types of marriage breakdown can be de- scribed. Why do marriages break down?One can seek to by his sample of divorcees:"These complaints answer this question from the participants'point were not the causes of the divorce-after all every of view or by reference to certain structural and still married wife could very likely make one or demographic variables-such as age of mar- more of these charges against her husband." riage-which regularly have been found to be as- Nevertheless,in seeking to understand marital sociated with likelihood of divorce.A rather well- breakdown,it would be wrong to disregard the established list of such variables now exists.In ad- testimony of those in the best position to know dition,the rapid increase in divorce among what went wrong in their own case.It may be,for younger cohorts indicates that youth itself is now instance,that certain structural conditions work a predictor of marital dissolution (Cherlin,1981). their effects through promoting certain types of Researchers have been inclined to regard these grievance.Goode's work suggests that this may be structural correlates as more worthy of explora- the case.For example,he found an association tion than the reasons given by couples for separat- between type of complaint and duration of mar- ing.This skepticism is perhaps understandable, riage,with a wife married for a short duration given the notoriously frequent disagreement be- likely to complain of her husband's personality tween husband and wife as to the cause of the and a wife married for 15 or more years to com- trouble and the changes that occur over time in plain of his drinking,adultery,and "helling their perceptions of the experience (Kitson and around.'Other studies make it clear that the Raschke,1981).Goode (1956:131)raises another divergence so commonly noted between the ac- point when he comments on the reasons advanced counts of husbands and wives is not random. Fulton (1979)speaks of "his',and "her"divorce and found wives in a large sample more critical of This project was funded by Macquarie University the ex-partners and of the marriages,more likely Research Grant.Thanks to Irene Lovelock (data collec- to report arguments and violence,and less likely tion)and David Cairns (data analysis). to feel that the marriages had been happy for much of the time.Levinger (1966)found wives School of Behavioural Sciences,Macquarie University,more likely to complain of cruelty,drinking, North Ryde,New South Wales 2113,Australia. physical and verbal abuse,neglect and lack of August 1984 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY 551 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Perceived Causes of Marriage Breakdown and Conditions of Life AILSA BURNS Macquarie University A large number of structural and attitudinal variables have been regularly found to be asso- ciated with marital dissolution. Fourteen such variables were located and related to the causes of breakdown as perceived by 335 divorced and separated men and women. Five perceived causes were associated with perceptions of the marriage as beginning to break down at particular time periods, but not with duration of marriage. Sex of respondent, SES, respondent's and spouse's religion, age at marriage, marital status (divorced or sepa- rated), parity of marriage, parental approval, stability of parents' and in-laws' marriages, length of premarital acquaintance, marriage duration and number of children, and stan- dard of living since separation all were associated with one or more of the reasons given by respondents for the marriage breakdown. An exploratory factor analysis gave a 7-factor solution supporting the notion that different types of marriage breakdown can be de- scribed. Why do marriages break down? One can seek to answer this question from the participants' point of view or by reference to certain structural and demographic variables-such as age of mar- riage-which regularly have been found to be as- sociated with likelihood of divorce. A rather well- established list of such variables now exists. In ad- dition, the rapid increase in divorce among younger cohorts indicates that youth itself is now a predictor of marital dissolution (Cherlin, 1981). Researchers have been inclined to regard these structural correlates as more worthy of explora- tion than the reasons given by couples for separat- ing. This skepticism is perhaps understandable, given the notoriously frequent disagreement be- tween husband and wife as to the cause of the trouble and the changes that occur over time in their perceptions of the experience (Kitson and Raschke, 1981). Goode (1956:131) raises another point when he comments on the reasons advanced This project was funded by Macquarie University Research Grant. Thanks to Irene Lovelock (data collec- tion) and David Cairns (data analysis). School of Behavioural Sciences, Macquarie University, North Ryde, New South Wales 2113, Australia. by his sample of divorcees: "These complaints were not the causes of the divorce-after all every still married wife could very likely make one or more of these charges against her husband." Nevertheless, in seeking to understand marital breakdown, it would be wrong to disregard the testimony of those in the best position to know what went wrong in their own case. It may be, for instance, that certain structural conditions work their effects through promoting certain types of grievance. Goode's work suggests that this may be the case. For example, he found an association between type of complaint and duration of mar- riage, with a wife married for a short duration likely to complain of her husband's personality and a wife married for 15 or more years to com- plain of his drinking, adultery, and "helling around." Other studies make it clear that the divergence so commonly noted between the ac- counts of husbands and wives is not random. Fulton (1979) speaks of "his" and "her" divorce and found wives in a large sample more critical of the ex-partners and of the marriages, more likely to report arguments and violence, and less likely to feel that the marriages had been happy for much of the time. Levinger (1966) found wives more likely to complain of cruelty, drinking, physical and verbal abuse, neglect and lack of August 1984 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY 551 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

love:husbands of in-law problems and sexual in-represented,with 270 of men and 2690 of compatibility. women's husbands in the semiskilled,unskilled, The present study aims to extend this line of and unemployed categories,compared with an research by exploring the associations between the estimated 20.4 semi-and unskilled in the reasons advanced by a sample of men and women general Australian population.The proportion of for the failure of their marriages,and a number of Roman Catholics was lower than that in the structural and demographic variables.Specifical- general population but higher than the average ly,these are sex of respondent,marital status proportion of divorced persons categorized as (divorced or separated),age at marriage,number Catholics in annual divorce statistics.Moreover, of times married,religion,socioeconomic status, these were just as likely as Protestants to be marital status of parents and spouse's parents, divorced (rather than separated),and 910 of still- duration of marriage,and number of children of married Roman Catholic women were intending the marriage.The study also includes a group of divorce.Immigrants from non-English-speaking variables that are not structural or demographic countries,currently a significant minority in the but that have been shown to be associated with Australian population,were underrepresented,no proneness to divorce.These are parental attitude doubt partly due to the fact that the study's pub- to the marriage,length of prior acquaintance, licity was restricted to the English-language point at which the marriage was seen as "begin- media. ning to break down,''and perceived current stan- Altogether 390 of the women and 350 of the dard of living compared with that pertaining dur- men were divorced,the remainder of the sample ing the marriage (Goode,1956:Fulton,1979: being separated only (this distribution cor- Thornes and Collard.1979). responds roughly to that obtaining in the Australian population at the time of the study: DESIGN Burns,1980).The age range was from 21 to 60 The Sample years,with the largest single group of both men The data come from a volunteer sample of 233 and women being aged 31-40.In 7007 of the women and 102 men,divorced or separated,who cases,the divorce or separation was of less than three-years standing.Men were somewhat more responded to publicity in metropolitan and sub- urban newspapers in Sydney,Australia.This likely to describe their spouses as the departing party (6000)than were women(5200).This sug- method was chosen because court records in gests that,as might be expected,people who saw Australia are confidential and not available to re- themselves as the injured party were particularly searchers,and because this project lacked the re- sources to seek out a random sample of divorced likely to have joined the study;and there was some evidence that this was the case (Burns, and separated men and women from the general 1980) population.The publicity took the form of short feature pieces describing the study as an investiga- The Questionnaire tion into the experience of divorce and separation The questionnaire comprised five sections: in Australia and calling for volunteers.Due to background material,causes and timing of the lack of interviewing resources,a self-report for- breakdown,experiences with the courts and with mat was used,and the questionnaire was distri- counseling agencies,reaction of children,current buted by mail to all men and women who con- tacted us(N 412).Of these,335 returned com- life situation and attitudes.In the present analysis,only the section on causes and a selection pleted (although not always fully completed) questionnaires.It is not possible to state how of variables from other sections is included.To assess causes respondents were offered a checklist representative the sample is of the divorced and of 18 reasons,based on Goode's list (1956)and separated people in Australia,since the character- istics of this population are not known.In the asked to check all items that were relevant in their own cases.The checklist was followed by an absence of this information,a comparison with open-response item. the general Australian population was made in terms of occupation,religion,and country of origin.The occupational distribution of male re Treatment of Data spondents and of female respondents'husbands Open responses were coded into the data,and proved to be very similar and only slightly higher all causes were coded as dichotomous variables than that of the general population (Burns,1980). (yes 1,no =2).Perceived onset of breakdown Given the usual tendency of volunteer samples to was collapsed for the main analysis into a 4-point be of higher SES (Moser and Kalton,1971),the scale(within the first year of marriage,2-5 years, lower occupational range was unexpectedly well- 6-10 years,and 11 years or later).Duration of 552 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

love; husbands of in-law problems and sexual in- compatibility. The present study aims to extend this line of research by exploring the associations between the reasons advanced by a sample of men and women for the failure of their marriages, and a number of structural and demographic variables. Specifical- ly, these are sex of respondent, marital status (divorced or separated), age at marriage, number of times married, religion, socioeconomic status, marital status of parents and spouse's parents, duration of marriage, and number of children of the marriage. The study also includes a group of variables that are not structural or demographic but that have been shown to be associated with proneness to divorce. These are parental attitude to the marriage, length of prior acquaintance, point at which the marriage was seen as "begin- ning to break down," and perceived current stan- dard of living compared with that pertaining dur- ing the marriage (Goode, 1956; Fulton, 1979; Thornes and Collard, 1979). DESIGN The Sample The data come from a volunteer sample of 233 women and 102 men, divorced or separated, who responded to publicity in metropolitan and sub- urban newspapers in Sydney, Australia. This method was chosen because court records in Australia are confidential and not available to re- searchers, and because this project lacked the re- sources to seek out a random sample of divorced and separated men and women from the general population. The publicity took the form of short feature pieces describing the study as an investiga- tion into the experience of divorce and separation in Australia and calling for volunteers. Due to lack of interviewing resources, a self-report for- mat was used, and the questionnaire was distri- buted by mail to all men and women who con- tacted us (N = 412). Of these, 335 returned com- pleted (although not always fully completed) questionnaires. It is not possible to state how representative the sample is of the divorced and separated people in Australia, since the character- istics of this population are not known. In the absence of this information, a comparison with the general Australian population was made in terms of occupation, religion, and country of origin. The occupational distribution of male re- spondents and of female respondents' husbands proved to be very similar and only slightly higher than that of the general population (Burns, 1980). Given the usual tendency of volunteer samples to be of higher SES (Moser and Kalton, 1971), the lower occupational range was unexpectedly well- represented, with 27% of men and 26% of women's husbands in the semiskilled, unskilled, and unemployed categories, compared with an estimated 20.4% semi- and unskilled in the general Australian population. The proportion of Roman Catholics was lower than that in the general population but higher than the average proportion of divorced persons categorized as Catholics in annual divorce statistics. Moreover, these were just as likely as Protestants to be divorced (rather than separated), and 91% of still- married Roman Catholic women were intending divorce. Immigrants from non-English-speaking countries, currently a significant minority in the Australian population, were underrepresented, no doubt partly due to the fact that the study's pub- licity was restricted to the English-language media. Altogether 39% of the women and 35% of the men were divorced, the remainder of the sample being separated only (this distribution cor- responds roughly to that obtaining in the Australian population at the time of the study: Burns, 1980). The age range was from 21 to 60 years, with the largest single group of both men and women being aged 31-40. In 70% of the cases, the divorce or separation was of less than three-years standing. Men were somewhat more likely to describe their spouses as the departing party (60%) than were women (52%). This sug- gests that, as might be expected, people who saw themselves as the injured party were particularly likely to have joined the study; and there was some evidence that this was the case (Burns, 1980). The Questionnaire The questionnaire comprised five sections: background material, causes and timing of the breakdown, experiences with the courts and with counseling agencies, reaction of children, current life situation and attitudes. In the present analysis, only the section on causes and a selection of variables from other sections is included. To assess causes respondents were offered a checklist of 18 reasons, based on Goode's list (1956) and asked to check all items that were relevant in their own cases. The checklist was followed by an open-response item. Treatment of Data Open responses were coded into the data, and all causes were coded as dichotomous variables (yes = 1, no = 2). Perceived onset of breakdown was collapsed for the main analysis into a 4-point scale (within the first year of marriage, 2-5 years, 6-10 years, and 11 years or later). Duration of 552 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

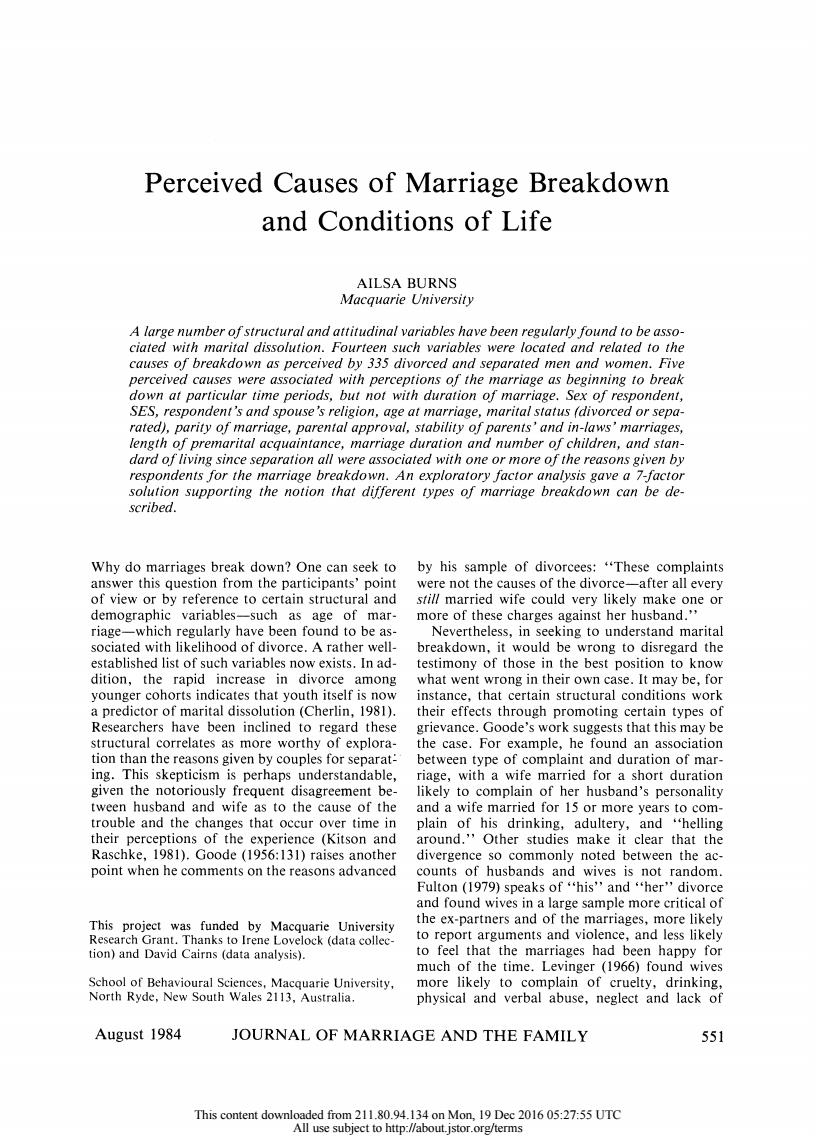

TABLE 1.PERCEIVED CAUSES OF MARRIAGE BREAKDOWN 0%of All Respondents 0%Men 0%Women Causesa (n=335) (n▣102) (n=233) Sexual incompatibility 45 56 40 Lack of communicationb 40 40 Husband's lack of time at home 40 28 46 Financial 2 Husband's association with another womanc 31 sandru 30 26 39 Wife's lack of interestt 25 Friction with relatives 23 21 Disagreements over children 0 Wife's association with angther manc 19 Husband's lack of interest 13 Wife's ill health 13 22 Inadequate housing 9 3 Religious differences Husband's gambling 5 3 Note:Percentages do not add up to 100.Multiple complaints are included. aCauses mentioned by less than 5 are not included. bIncludes lack of common interests. and mentioncd. eIncludes wife's perception of husband as having sadistic, cruel,or brutal personality. fincludes statement of resentment about the lack of stimulation. marriage was coded as a 6-point scale (2,2-5, ate analyses,but probability values between .01 6-10,11-15,16-20 and 20+years).Other vari- and,05 are reported in Table 2 as indicating inter- ables included in the analysis were sex of respon- esting trends.Subsidiary analyses include correla- dent;marital status of respondent (divorced or tions and an exploratory factor analysis (BMD separated);whether the marriage and separation P4M:Principal Components DQUART,non- being described was the first or not;number of orthogonal rotation). children;parental attitudes to the marriage (strongly approve,approve,neutral [including don't know],disapprove,or strongly disapprove); RESULTS length of acquaintance prior to marriage (7-point scale:0-3,3-6,6-12 months,12 months to 2 Sex Differences in Perceived Causes years,2,3-5,and 5+years).Respondents'evalu- of the Breakdown ations of their present standards of living was Most respondents indicated that the breakdown coded as higher,similar to,somewhat lower,or had multiple causes.The most commonly nomi- much lower than that obtaining during the mar- nated causes are presented in Table 1.The most riage.Socioeconomic status was rated on a frequent complaint is sexual incompatibility, 7-point scale (Congalton,1969)using (ex-)hus- which was mentioned by 56%of the men and band's occupation,with an extra category in- 40%of the women.The next most common com- cluded for unemployed/retired husbands.Reli- plaint is lack of common interests/lack of com- gion was collapsed into Protestant,Roman munication.With respect to other complaints, Catholic,and nonbeliever,with the small number there is somewhat less agreement between of persons of other faiths excluded from these husbands and wives,with wives more likely to analyses.Parental marriages were coded as intact, mention the husband's lack of time at home and divorced,separated,or widowed. his adultery,cruelty,and drinking,while Analysis husbands focused on the wife's adultery and fric- tion with relatives.It is worth noting,however, A series of SPSS MANOVA were run,with the that over one-fourth of the men mention their 15 most commonly nominated causes (plus an own lack of time at home,the top complaint "other",category)treated as the outcome set. among the wives.The sex difference is highly sig- Where data were missing or could not be fitted in- nificant (F=7.78,df=16,311,p<.000:Table to the coding scheme,these cases were dropped 2,column 1).The univariate analyses show that from that particular analysis.As a result,degrees the significant differences occur on complaints of of freedom vary between analyses.In view of the husband's adultery,drinking,cruelty,and lack of large number of variables,a conservative proba- time at home;housing and financial problems bility figure (p =.01)is adopted for the univari- (wives nominated these more frequently);and August 1984 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY 553 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

I -DLL 1. rt-Lh\.I v AL/UJ ` UL r IVIALIAII/-\jI DI__lAiLWJJV VV IN % of All Respondents % Men % Women Causesa (n = 335) (n = 102) (n = 233) Sexual incompatibility 45 56 40 Lack of communicationb 40 41 40 Husband's lack of time at home 40 28 46 Financial 32 24 36 Husband's association with another womanc 31 17 37 Husband's drinkingd 30 17 36 Husband's crueltye 26 37 4 Wife's lack of interestf 26 25 26 Friction with relatives 23 29 21 Disagreements over children 20 22 19 Wife's association with anQther manC 19 35 12 Husband's lack of interest1 13 15 12 Wife's ill health 13 13 13 Inadequate housing 9 4 13 Religious differences 5 5 5 Husband's gambling 5 3 7 Note: Percentages do not add up to 100. Multiple complaints are included. aCauses mentioned by less than 5% are not included. bIncludes lack of common interests. CNo homosexual relationships were mentioned. dlncludes husband's alcoholism. eIncludes wife's perception of husband as having sadistic, cruel, or brutal personality. fIncludes statement of resentment about the lack of stimulation. marriage was coded as a 6-point scale ( ' r A' T A TCE'C f' A NAD I A I".R DD A VNrAn\ i'XT August 1984 553 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

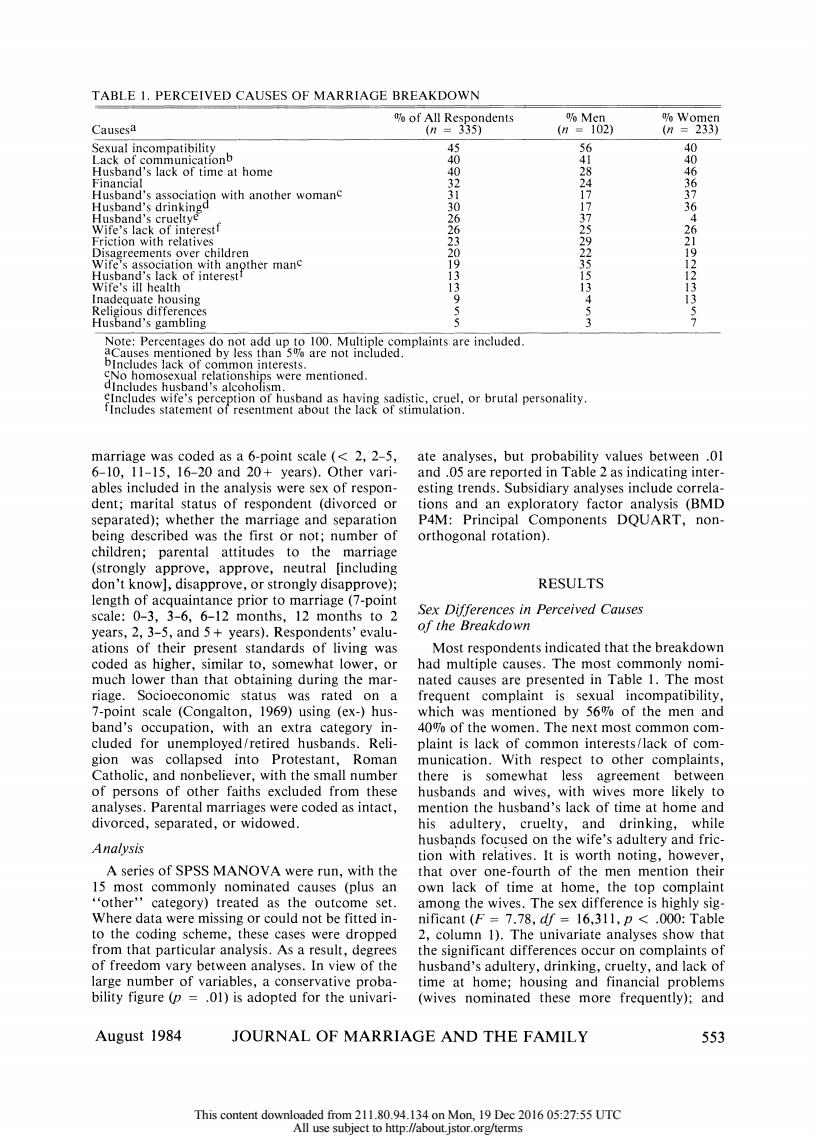

wife's adultery and sexual incompatibility with the 1:2 and 1:3 contrast significant.Hus- (husbands nominated these more frequently). band's cruelty is concentrated in period 1,and the contrast between this and all other onset periods is Perceived Onset of the Breakdown significant. Both men and women,but particularly women, perceived the marriage as beginning to break Socioeconomic Status down early.Fifteen percent of the wives dated the SES also was significantly associated with per- onset of breakdown within the first three months ceived causes of breakdown (F 1.59,df= of marriage.Most couples,however,did not sepa- 16,272,p =.023),the two significant contribut- rate until much later (Figure).The sex difference ing causes being husband's drinking (p =.011) is highly significant (F=2.47,df=16,319,p< and husband's cruelty (p<.000).The relation- .001). ship is an inverse one.Only 170 of women mar- Were particular problems associated with ried to men in higher professional or managerial earlier or later recognition that the marriage was occupations complained about alcohol,whereas failing?Table 2(column 3)shows that they were 70%%of women married to unskilled men and all (multivariate F 2.47,df=16,319,p<.000). women whose husbands were unemployed or re- The univariate analyses show that five causes are tired made this complaint.The trends are vaguer associated with particular breakdown periods: among the smaller number of men (13)who saw husband's drinking (p <.000),husband's cruelty their own drinking as a problem,but none of (p<.000),sexual incompatibility (p =.004),dis- these were in the two top-SES categories.Com- agreements over children (p =.014),and an plaints of husband's cruelty were most common “other woman”(p<.032).Mean values(Table among wives of men in the semiskilled(470%)un- 3)indicate that complaints of sexual incompatibil- skilled (57%)and unemployed/retired categories ity rise from a high base in onset period 1 (0-12 (50%).(It should be borne in mind that cruelty months)to a peak in period 3(6-10 years),fol- was self-defined by respondents and included be- lowed by a sharp decline in period 4(11+years). haviors other than physical cruelty.There was The contrast between periods 1:4 and 3:4 was sig- also a relationship between SES and perceived nificant beyond the.05 level.The "other onset of the breakdown,with semiskilled and un- woman"'cause rises steadily from period 1 skilled men being particularly likely to attribute through to period 4,with the gains from 1:3 and the breakdown to their wife's adultery in the 1:4 being significant.Disagreements over children period between 2 and 10 years after marriage. are concentrated in period 2(2-5 years),but only the contrast between periods 2:4 is significant. Religion Husband's drinking is most commonly mentioned The multivariate F value for respondent's reli- by those who nominate onset periods 1 and 4, gion is not significant,but there is a trend towards significance with respect to two causes,husband's lack of time at home (p=.024)and husband's FIGURE.PERCEIVED ONSET OF BREAKDOWN drinking (p =.041).In both cases the complaint AND TIME TO SEPARATION was most common among Roman Catholics and least common among those with no religious affil- Per Cent iation.When the sample is divided by sex,it 40 -----Onset Women emerges that religious beliefs have an opposite ef- -Onset Men fect on men and women with respect to sexual Time to Separation complaints (p =.003).Women with no religious 30 affiliation were particularly likely to see sexual in- compatibility as a cause of the marriage break- down,whereas it was the men with a religious af- filiation (of any kind)who were likely to make 20 this attribution.Spouses'religion was not a sig- nificant influence,although the univariate values show that lack of communication is somewhat 10 more commonly complained of by those with a Roman Catholic spouse,least by those with one of no religious affiliation (p =.049).The interac- tion between spouse's religion and sex of respon- dent,however,is highly significant (F=1.79, 1 Year 5 Years 10 Years 15 Years 20+Years df=16,306,p =.005),and four complaints 554 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

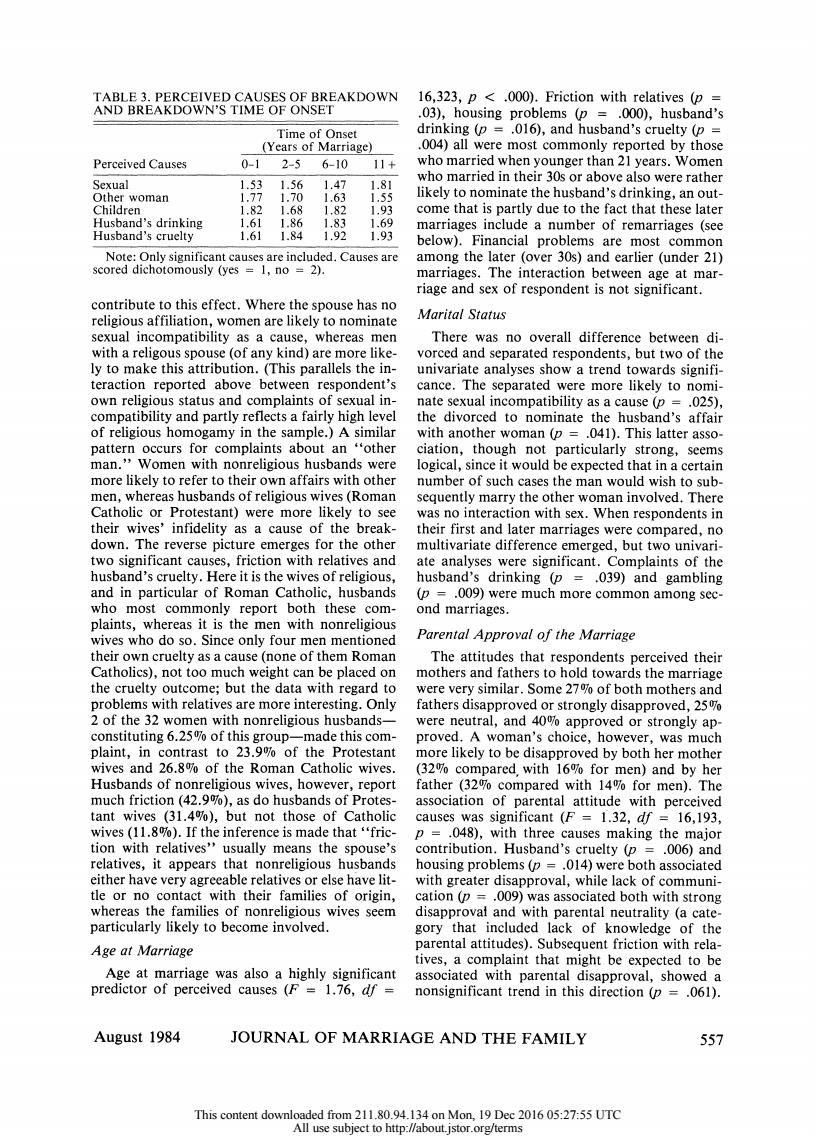

wife's adultery and sexual incompatibility (husbands nominated these more frequently). Perceived Onset of the Breakdown Both men and women, but particularly women, perceived the marriage as beginning to break down early. Fifteen percent of the wives dated the onset of breakdown within the first three months of marriage. Most couples, however, did not sepa- rate until much later (Figure). The sex difference is highly significant (F = 2.47, df = 16,319, p < .001). Were particular problems associated with earlier or later recognition that the marriage was failing? Table 2 (column 3) shows that they were (multivariate F = 2.47, df = 16,319, p < .000). The univariate analyses show that five causes are associated with particular breakdown periods: husband's drinking (p < .000), husband's cruelty (p < .000), sexual incompatibility (p = .004), dis- agreements over children (p = .014), and an "other woman" (p < .032). Mean values (Table 3) indicate that complaints of sexual incompatibil- ity rise from a high base in onset period 1 (0-12 months) to a peak in period 3 (6-10 years), fol- lowed by a sharp decline in period 4 (11 + years). The contrast between periods 1:4 and 3:4 was sig- nificant beyond the .05 level. The "other woman" cause rises steadily from period 1 through to period 4, with the gains from 1:3 and 1:4 being significant. Disagreements over children are concentrated in period 2 (2-5 years), but only the contrast between periods 2:4 is significant. Husband's drinking is most commonly mentioned by those who nominate onset periods 1 and 4, FIGURE. PERCEIVED ONSET OF BREAKDOWN AND TIME TO SEPARATION Per Cent 40 - -- Onse Onse - - Time 30 - 20 - 10 - \ K\ J 1 Year 5 Years 10 Years 15 YE t Women t Men to Separation i ears 20+ Years with the 1:2 and 1:3 contrast significant. Hus- band's cruelty is concentrated in period 1, and the contrast between this and all other onset periods is significant. Socioeconomic Status SES also was significantly associated with per- ceived causes of breakdown (F = 1.59, df = 16,272, p = .023), the two significant contribut- ing causes being husband's drinking (p = .011) and husband's cruelty (p < .000). The relation- ship is an inverse one. Only 17070 of women mar- ried to men in higher professional or managerial occupations complained about alcohol, whereas 700% of women married to unskilled men and all women whose husbands were unemployed or re- tired made this complaint. The trends are vaguer among the smaller number of men (13) who saw their own drinking as a problem, but none of these were in the two top-SES categories. Com- plaints of husband's cruelty were most common among wives of men in the semiskilled (47%0) un- skilled (57%0) and unemployed/retired categories (500o). (It should be borne in mind that cruelty was self-defined by respondents and included be- haviors other than physical cruelty.) There was also a relationship between SES and perceived onset of the breakdown, with semiskilled and un- skilled men being particularly likely to attribute the breakdown to their wife's adultery in the period between 2 and 10 years after marriage. Religion The multivariate F value for respondent's reli- gion is not significant, but there is a trend towards significance with respect to two causes, husband's lack of time at home (p = .024) and husband's drinking (p = .041). In both cases the complaint was most common among Roman Catholics and least common among those with no religious affil- iation. When the sample is divided by sex, it emerges that religious beliefs have an opposite ef- fect on men and women with respect to sexual complaints (p = .003). Women with no religious affiliation were particularly likely to see sexual in- compatibility as a cause of the marriage break- down, whereas it was the men with a religious af- filiation (of any kind) who were likely to make this attribution. Spouses' religion was not, a sig- nificant influence, although the univariate values show that lack of communication is somewhat more commonly complained of by those with a Roman Catholic spouse, least by those with one of no religious affiliation (p = .049). The interac- tion between spouse's religion and sex of respon- dent, however, is highly significant (F = 1.79, df = 16,306, p = .005), and four complaints 554 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

181 1000.1 月 得 娟 3 s001 绳 的 鲤 2001 3 的 好 娟 S3S 理 娟 系 导3 3 3 3 得 剪 是 爱 60o 000:) 29.g (10) (ZO) EE'IZ 000.1 15S (600) uonestunwwo sasne uewoM ay1O ButsnoH aouasqe s,pueqsnH zuques s pueqsnH Al[anIo s,pueqsnH salolu!s,pueqsnH [epueut August 1984 JOURNAL OF MArriage AND THE FAMILY 555 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

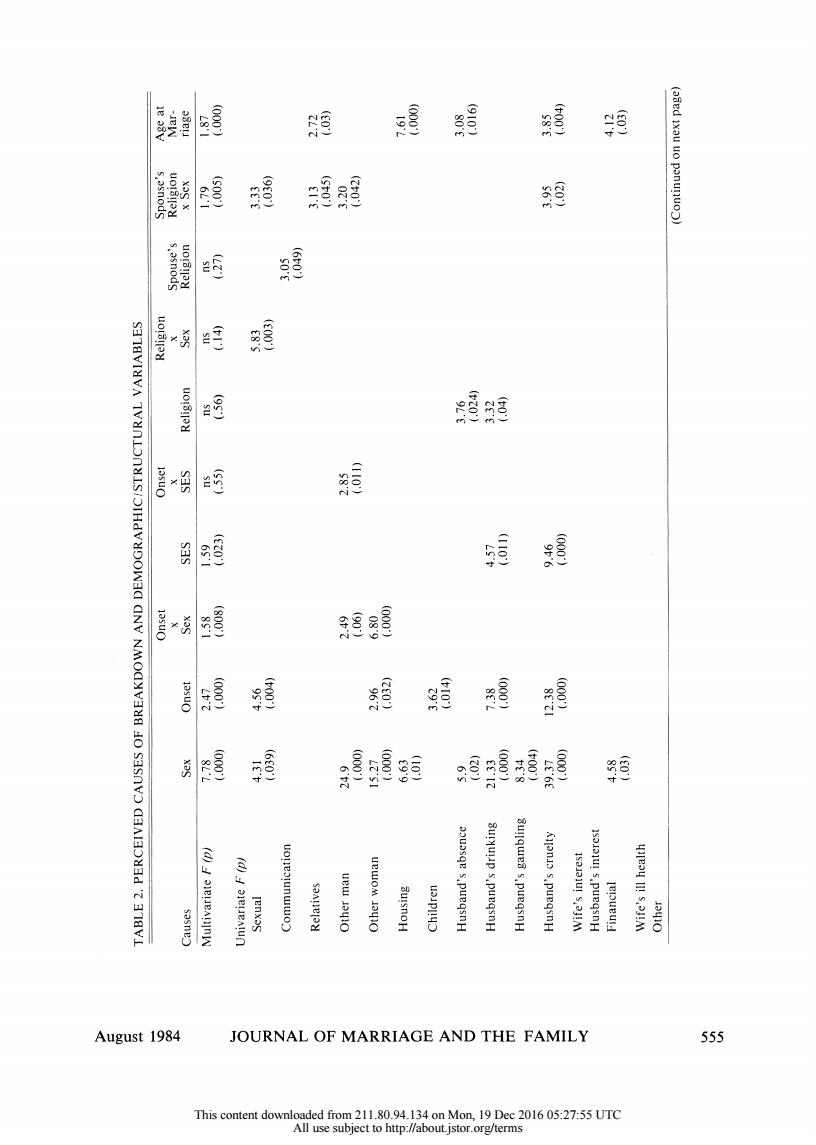

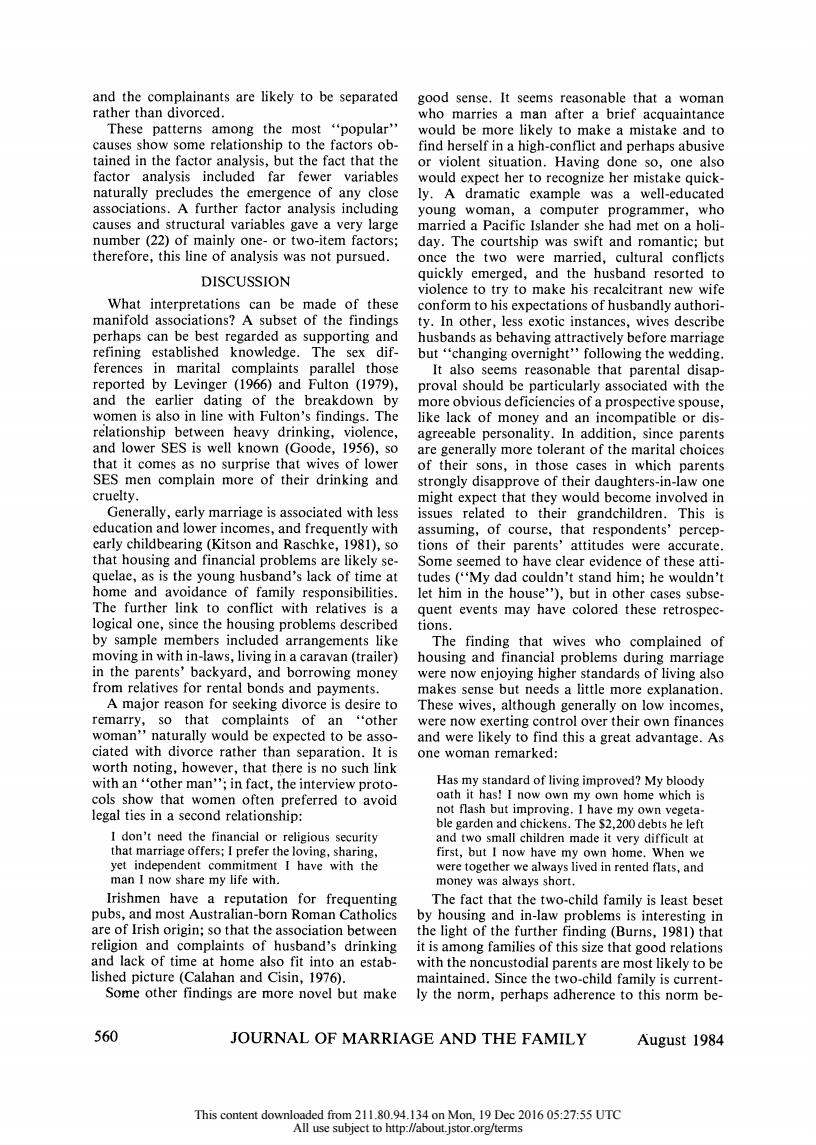

TABLE 2. PERCEIVED CAUSES OF BREAKDOWN AND DEMOGRAPHIC/STRUCTURAL VARIABLES Onset Onset Religion Spouse's Age at x x x Spouse's Religion Mar- Causes Sex Onset Sex SES SES Religion Sex Religion x Sex riage Multivariate F (p) 7.78 2.47 1.58 1.59 ns ns ns ns 1.79 1.87 (.000) (.000) (.008) (.023) (.55) (.56) (.14) (.27) (.005) (.000) Univariate F (p) Sexual Communication 4.31 4.56 (.039) (.004) Other man 24.9 2.49 (.000) (.06) Other woman 15.27 2.96 6.80 (.000) (.032) (.000) Housing 6.63 (.01) Children 3.62 (.014) Husband's absence 5.9 (.02) Husband's drinking 21.33 7.38 (.000) (.000) Husband's gambling 8.34 (.004) Husband's cruelty 39.37 12.38 (.000) (.000) Wife's interest Husband's interest Financial 4.58 (.03) Wife's ill health Other 5.83 (.003) 3.05 (.049) 2.85 (.011) 3.33 (.036) 3.13 2.72 (.045) (.03) 3.20 (.042) 7.61 (.000) 3.76 (.024) 3.32 (.04) 4.57 (.011) 9.46 (.000) 3.95 (.02) 3.08 (.016) 3.85 (.004) 4.12 (.03) (Continued on next page) Lfn (A Relatives C-4 0 z CT1 0 tTI Hoz C"1 t3 0-= 3, r;3 "Ti This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

图 照 8 (000.1 uoneing 的 照 uaipl4 3 aoue 6 媚 000.1 理 reluaed ③ (850) 生爱 3 谓 三 aeeW 蜗 0 美 组 婚 sasayiuaed ul ae saungy Ailqeqold 'papnpout iou ale /p pue sawooino lueouluzIsuoN :a1ON lenxas uoneolunwwo uew jaqlO ZuisnoH oouasqe s,pueqsnH urxuup s.pueqsnH Bulques s,pueqsnH Kiano s,pueqsnH saoul s,pueqsnH [eroueuly 556 JOURNAL OF MArRiAge AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

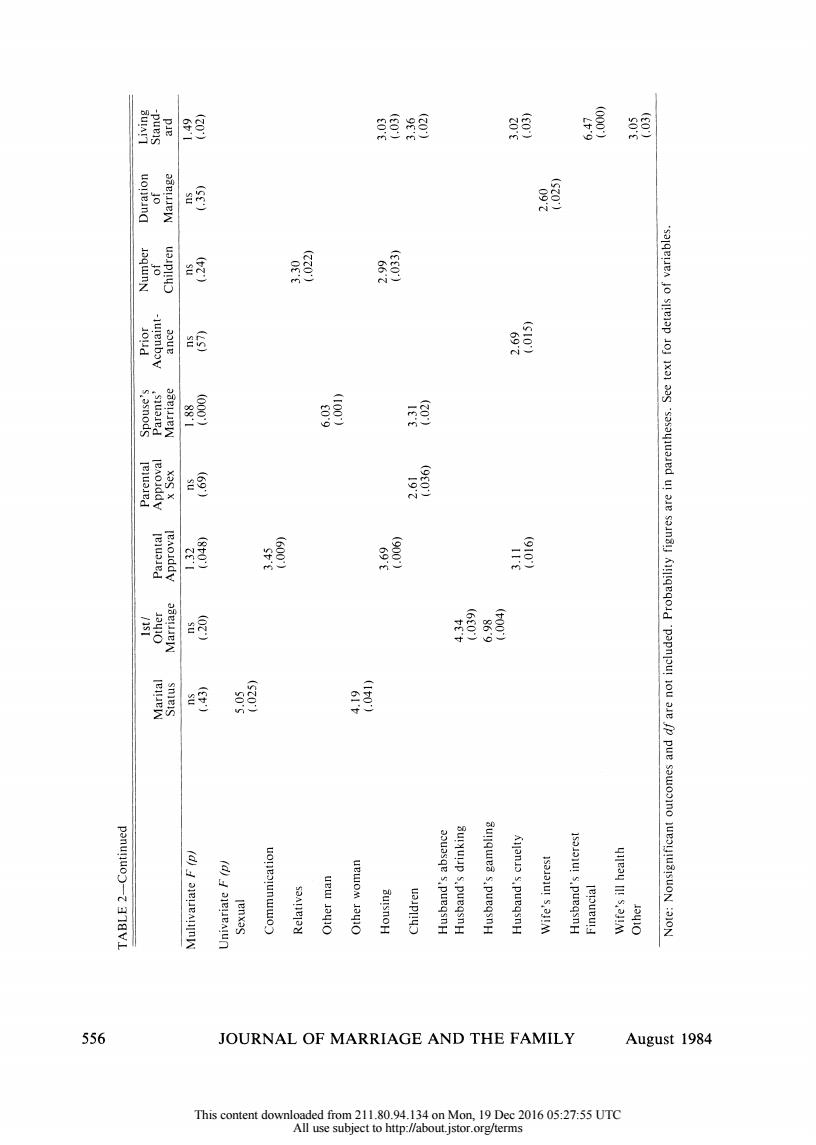

TABLE 2-Continued lst/ Parental Spouse's Prior Number Duration Living Marital Other Parental Approval Parents' Acquaint- of of Stand- Status Marriage Approval x Sex Marriage ance Children Marriage ard Multivariate F (p) ns ns 1.32 ns 1.88 ns ns ns 1.49 (.43) (.20) (.048) (.69) (.000) (57) (.24) (.35) (.02) t- Univariate F (p) C Sexual 5.05 t^~~~~~d~~~~~ ~~~(.025) Z Communication 3.45 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~> ~~~~~(.009) 0 (.022) ~~r ~ Relatives 3.30 Other man 6.03 (.001) > Other woman 4.19 (.041) > (.006) (.033) (.03) c^ ~ Housing 3.69 2.99 3.03 " Children 2.61 3.31 3.36 (.036) (.02) (.02) z Husband's absence t3~U ~ Husband's drinking 4.34 ...]Hc3~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~(.039) =dI Husband's gambling 6.98 r't (.004) > (.016) (.015) (.03) rt^ ~ Husband's cruelty 3.11 2.69 3.02 [-.. (.025) Wife's interest 2.60 C<^C ~ Husband's interest Financial 6.47 (.000) Wife's ill health cI (.03) C Other 3.05 o'~ oNote: Nonsignificant outcomes and df are not included. Probability figures are in parentheses. See text for details of variables. o0 -t^ This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

TABLE 3.PERCEIVED CAUSES OF BREAKDOWN 16,323,p <.000).Friction with relatives (p AND BREAKDOWN'S TIME OF ONSET .03),housing problems (p =.000),husband's Time of Onset drinking (p =.016),and husband's cruelty (p (Years of Marriage) .004)all were most commonly reported by those Perceived Causes 0-12-5 6-10 11+ who married when younger than 21 years.Women Sexual who married in their 30s or above also were rather 1.53 1.56 1.47 1.81 Other woman 1.77 170 1.63 155 likely to nominate the husband's drinking,an out- Children 1.82 1.68 1.82 1.93 come that is partly due to the fact that these later Husband's drinking 1.61 1.86 1.83 1.69 marriages include a number of remarriages (see Husband's cruelty 1.61 1.84 1.92 1.93 below).Financial problems are most common Note:Only significant causes are included.Causes are among the later (over 30s)and earlier (under 21) scored dichotomously (yes 1,n0=2). marriages.The interaction between age at mar- riage and sex of respondent is not significant. contribute to this effect.Where the spouse has no religious affiliation,women are likely to nominate Marital Status sexual incompatibility as a cause,whereas men There was no overall difference between di- with a religous spouse (of any kind)are more like- vorced and separated respondents,but two of the ly to make this attribution.(This parallels the in- univariate analyses show a trend towards signifi- teraction reported above between respondent's cance.The separated were more likely to nomi- own religious status and complaints of sexual in- nate sexual incompatibility as a cause (p =.025), compatibility and partly reflects a fairly high level the divorced to nominate the husband's affair of religious homogamy in the sample.)A similar with another woman (p =.041).This latter asso- pattern occurs for complaints about an "other ciation,though not particularly strong,seems man."Women with nonreligious husbands were logical,since it would be expected that in a certain more likely to refer to their own affairs with other number of such cases the man would wish to sub- men,whereas husbands of religious wives (Roman sequently marry the other woman involved.There Catholic or Protestant)were more likely to see was no interaction with sex.When respondents in their wives'infidelity as a cause of the break- their first and later marriages were compared,no down.The reverse picture emerges for the other multivariate difference emerged,but two univari- two significant causes,friction with relatives and ate analyses were significant.Complaints of the husband's cruelty.Here it is the wives of religious, husband's drinking (p =.039)and gambling and in particular of Roman Catholic,husbands (p =.009)were much more common among sec- who most commonly report both these com- ond marriages. plaints,whereas it is the men with nonreligious wives who do so.Since only four men mentioned Parental Approval of the Marriage their own cruelty as a cause (none of them Roman The attitudes that respondents perceived their Catholics),not too much weight can be placed on mothers and fathers to hold towards the marriage the cruelty outcome;but the data with regard to were very similar.Some 27%of both mothers and problems with relatives are more interesting.Only fathers disapproved or strongly disapproved,25 2 of the 32 women with nonreligious husbands- were neutral,and 40%%approved or strongly ap- constituting 6.25 of this group-made this com- proved.A woman's choice,however,was much plaint,in contrast to 23.9%of the Protestant more likely to be disapproved by both her mother wives and 26.8%of the Roman Catholic wives. (32%compared,with 16%0 for men)and by her Husbands of nonreligious wives,however,report father (320%compared with 14%for men).The much friction(42.9%),as do husbands of Protes- association of parental attitude with perceived tant wives (31.4%),but not those of Catholic causes was significant (F 1.32,df 16,193, wives (11.8%).If the inference is made that"fric- p=.048),with three causes making the major tion with relatives"usually means the spouse's contribution.Husband's cruelty (p =.006)and relatives,it appears that nonreligious husbands housing problems (p =.014)were both associated either have very agreeable relatives or else have lit- with greater disapproval,while lack of communi- tle or no contact with their families of origin, cation (p =.009)was associated both with strong whereas the families of nonreligious wives seem disapproval and with parental neutrality (a cate- particularly likely to become involved. gory that included lack of knowledge of the Age at Marriage parental attitudes).Subsequent friction with rela- tives,a complaint that might be expected to be Age at marriage was also a highly significant associated with parental disapproval,showed a predictor of perceived causes (F 1.76,df nonsignificant trend in this direction (p =.061). August 1984 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY 557 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.istor.org/terms

TABLE 3. PERCEIVED CAUSES OF BREAKDOWN AND BREAKDOWN'S TIME OF ONSET Time of Onset (Years of Marriage) Perceived Causes 0-1 2-5 6-10 11 + Sexual 1.53 1.56 1.47 1.81 Other woman 1.77 1.70 1.63 1.55 Children 1.82 1.68 1.82 1.93 Husband's drinking 1.61 1.86 1.83 1.69 Husband's cruelty 1.61 1.84 1.92 1.93 Note: Only significant causes are included. Causes are scored dichotomously (yes = 1, no = 2). contribute to this effect. Where the spouse has no religious affiliation, women are likely to nominate sexual incompatibility as a cause, whereas men with a religous spouse (of any kind) are more like- ly to make this attribution. (This parallels the in- teraction reported above between respondent's own religious status and complaints of sexual in- compatibility and partly reflects a fairly high level of religious homogamy in the sample.) A similar pattern occurs for complaints about an "other man." Women with nonreligious husbands were more likely to refer to their own affairs with other men, whereas husbands of religious wives (Roman Catholic or Protestant) were more likely to see their wives' infidelity as a cause of the break- down. The reverse picture emerges for the other two significant causes, friction with relatives and husband's cruelty. Here it is the wives of religious, and in particular of Roman Catholic, husbands who most commonly report both these com- plaints, whereas it is the men with nonreligious wives who do so. Since only four men mentioned their own cruelty as a cause (none of them Roman Catholics), not too much weight can be placed on the cruelty outcome; but the data with regard to problems with relatives are more interesting. Only 2 of the 32 women with nonreligious husbands- constituting 6.25%7o of this group-made this com- plaint, in contrast to 23.9% of the Protestant wives and 26.8% of the Roman Catholic wives. Husbands of nonreligious wives, however, report much friction (42.9%), as do husbands of Protes- tant wives (31.4%), but not those of Catholic wives (11.807). If the inference is made that "fric- tion with relatives" usually means the spouse's relatives, it appears that nonreligious husbands either have very agreeable relatives or else have lit- tle or no contact with their families of origin, whereas the families of nonreligious wives seem particularly likely to become involved. Age at Marriage Age at marriage was also a highly significant predictor of perceived causes (F = 1.76, df = 16,323, p < .000). Friction with relatives (p = .03), housing problems (p = .000), husband's drinking (p = .016), and husband's cruelty (p = .004) all were most commonly reported by those who married when younger than 21 years. Women who married in their 30s or above also were rather likely to nominate the husband's drinking, an out- come that is partly due to the fact that these later marriages include a number of remarriages (see below). Financial problems are most common among the later (over 30s) and earlier (under 21) marriages. The interaction between age at mar- riage and sex of respondent is not significant. Marital Status There was no overall difference between di- vorced and separated respondents, but two of the univariate analyses show a trend towards signifi- cance. The separated were more likely to nomi- nate sexual incompatibility as a cause (p = .025), the divorced to nominate the husband's affair with another woman (p = .041). This latter asso- ciation, though not particularly strong, seems logical, since it would be expected that in a certain number of such cases the man would wish to sub- sequently marry the other woman involved. There was no interaction with sex. When respondents in their first and later marriages were compared, no multivariate difference emerged, but two univari- ate analyses were significant. Complaints of the husband's drinking (p = .039) and gambling (p = .009) were much more common among sec- ond marriages. Parental Approval of the Marriage The attitudes that respondents perceived their mothers and fathers to hold towards the marriage were very similar. Some 27% of both mothers and fathers disapproved or strongly disapproved, 25% were neutral, and 40% approved or strongly ap- proved. A woman's choice, however, was much more likely to be disapproved by both her mother (32% compared, with 16% for men) and by her father (32% compared with 14%7o for men). The association of parental attitude with perceived causes was significant (F = 1.32, df = 16,193, p = .048), with three causes making the major contribution. Husband's cruelty (p = .006) and housing problems (p = .014) were both associated with greater disapproval, while lack of communi- cation (p = .009) was associated both with strong disapproval and with parental neutrality (a cate- gory that included lack of knowledge of the parental attitudes). Subsequent friction with rela- tives, a complaint that might be expected to be associated with parental disapproval, showed a nonsignificant trend in this direction (p = .061). August 1984 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY 557 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Those men who nominated disagreements over stance,that the larger the family the greater the children as a cause of breakdown were particular- housing difficulties.The mean values show,how- ly likely to describe strongly disapproving parents ever,that it is among three-child families that (p =.036).For both men and women,parental these complaints are most common,followed by approval was associated with higher SES(r =.17, one-child families,larger families(4+),and lastly p =.02)and with a drop in living standards two-child families. following the separation (r =.17,p =.02;see below). Standard of Living After Divorce Respondents'evaluations of their standards of Parental Marital Stability living following separation or divorce were signifi- Twenty-one percent of the respondents'parents cantly associated with causes (F=1.49,df= and 24 of their spouses'parents were reported 16,320,p =.02).Those people who reported to have been divorced or separated.This is some- financial (p<.000)and housing (p =.03)prob- what higher than the incidence of 18.9(18.3 lems considered that their standards of living were for women and 19%%for men)in a sample of still now higher than during their marriages,while married Australian couples interviewed at a simi- those who reported disagreements over children lar time (Antill and Cunningham,personal com- (p =.02)evaluated their living standards as munication)but in line with the general finding lower.The relationship with husband's cruelty from the U.S.A.that there is a modest amount of (p =.03)was curvilinear;i.e.,these women's liv- intergenerational transmission of marital break- ing standards were now described as either higher down (Kitson and Raschke,1981).Nearly one- or much lower.A greater drop in standard of liv- third (30%)of those respondents who came from ing was reported by those of higher SES(r =.27, divorced or separated homes had married spouses p=.001). from a similar background.(It was not possible to estimate the likelihood of such homogamy in the Duration of Marriage general population,given the broad age range of As the Figure shows,many couples continued the sample and the absence of population statis- to live together for considerable periods after the tics that would indicate the likelihood of persons time at which they felt their marriages had begun within this range coming from dissolved mar- to break down-26 years in one case.The pa- riages.) tience of wives is particularly notable;although Marital status of the respondents'parents was half of the women considered the breakdown to not significantly associated with any of the have occurred within two years of marriage,the marital complaints,but that of the spouses' great majority stayed with their husbands for a parents was (F 1.88,df 16,314,p<.001). further 5 to 20 years.Perhaps because of this dis- The relevant causes are an "other man''(p< crepancy between attitudes and behavior,dura- .000)and disagreements over children (p =.02). tion of marriage did not emerge as a strong The direction of the association was unexpected: predictor,although there is a seemingly logical in each case it is the widowed parents who stand association between length of marriage and wife's out from all others. loss of interest in the marriage (p =.025).Dura- Acquaintance Before Marriage tion of marriage is associated,however,with spouse's religion (F=3.31,df 2,309,p =.02). There is no overall association with length of Religiously homogamous marriages have the acquaintance before marriage,but the univariate longest duration,with the most longstanding be- analyses showed that those who had known their ing those between two nonbelievers.The briefest spouses for the shortest period of time (0-3 marriages were those between a Protestant and a months)were more likely to nominate husband's Roman Catholic and between a Protestant and a cruelty as a cause.Age at marriage and premarital nonbeliever.When the data were analyzed sepa- acquaintance period were not correlated (r rately for men and women,it emerged that wives 06). whose ex-husbands were Roman Catholics had ex- Number of Children perienced the shortest marriages.The husbands in these cases were significantly less likely than all Again,the multivariate Fis not significant,but others to maintain contact with children after the friction with relatives (p =.022)and housing separation (F=4.45,df 2,309,p =.01). problems (p =.033)both show a trend towards association with number of children.Interesting- Associations Among Perceived Causes ly,this is not a strictly linear function,as might The analyses reported above suggested that cer- perhaps be expected;it would seem logical,for in- tain marital complaints tended to cluster together. 558 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Those men who nominated disagreements over children as a cause of breakdown were particular- ly likely to describe strongly disapproving parents (p = .036). For both men and women, parental approval was associated with higher SES (r = .17, p = .02) and with a drop in living standards following the separation (r = .17, p = .02; see below). Parental Marital Stability Twenty-one percent of the respondents' parents and 24%o of their spouses' parents were reported to have been divorced or separated. This is some- what higher than the incidence of 18.9% (18.3% for women and 19% for men) in a sample of still married Australian couples interviewed at a simi- lar time (Antill and Cunningham, personal com- munication) but in line with the general finding from the U.S.A. that there is a modest amount of intergenerational transmission of marital break- down (Kitson and Raschke, 1981). Nearly one- third (30%) of those respondents who came from divorced or separated homes had married spouses from a similar background. (It was not possible to estimate the likelihood of such homogamy in the general population, given the broad age range of the sample and the absence of population statis- tics that would indicate the likelihood of persons within this range coming from dissolved mar- riages.) Marital status of the respondents' parents was not significantly associated with any of the marital complaints, but that of the spouses' parents was (F = 1.88, df = 16,3i4, p < .001). The relevant causes are an "other man" (p < .000) and disagreements over children (p = .02). The direction of the association was unexpected: in each case it is the widowed parents who stand out from all others. Acquaintance Before Marriage There is no overall association with length of acquaintance before marriage, but the univariate analyses showed that those who had known their spouses for the shortest period of time (0-3 months) were more likely to nominate husband's cruelty as a cause. Age at marriage and premarital acquaintance period were not correlated (r = .06). Number of Children Again, the multivariate F is not significant, but friction with relatives (p = .022) and housing problems (p = .033) both show a trend towards association with number of children. Interesting- ly, this is not a strictly linear function, as might perhaps be expected; it would seem logical, for in- stance, that the larger the family the greater the housing difficulties. The mean values show, how- ever, that it is among three-child families that these complaints are most common, followed by one-child families, larger families (4 +), and lastly two-child families. Standard of Living After Divorce Respondents' evaluations of their standards of living following separation or divorce were signifi- cantly associated with causes (F = 1.49, df = 16,320, p = .02). Those people who reported financial (p < .000) and housing (p = .03) prob- lems considered that their standards of living were now higher than during their marriages, while those who reported disagreements over children (p = .02) evaluated their living standards as lower. The relationship with husband's cruelty (p = .03) was curvilinear; i.e., these women's liv- ing standards were now described as either higher or much lower. A greater drop in standard of liv- ing was reported by those of higher SES (r = .27, p = .001). Duration of Marriage As the Figure shows, many couples continued to live together for considerable periods after the time at which they felt their marriages had begun to break down-26 years in one case. The pa- tience of wives is particularly notable; although half of the women considered the breakdown to have occurred within two years of marriage, the great majority stayed with their husbands for a further 5 to 20 years. Perhaps because of this dis- crepancy between attitudes and behavior, dura- tion of marriage did not emerge as a strong predictor, although there is a seemingly logical association between length of marriage and wife's loss of interest in the marriage (p = .025). Dura- tion of marriage is associated, however, with spouse's religion (F = 3.31, df = 2,309, p = .02). Religiously homogamous marriages have the longest duration, with the most longstanding be- ing those between two nonbelievers. The briefest marriages were those between a Protestant and a Roman Catholic and between a Protestant and a nonbeliever. When the data were analyzed sepa- rately for men and women, it emerged that wives whose ex-husbands were Roman Catholics had ex- perienced the shortest marriages. The husbands in these cases were significantly less likely than all others to maintain contact with children after the separation (F = 4.45, df = 2,309, p = .01). Associations Among Perceived Causes The analyses reported above suggested that cer- tain marital complaints tended to cluster together. 558 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

TABLE 4.PERCEIVED CAUSES,MARITAL STATUS,AND SEX OF RESPONDENT.ROTATED FACTOR SOLUTION (PRINCIPAL COMPONENTS DOUART.NONORTHOGONAL ROTATION) Perceived Causes Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 Factor 5 Factor 6 Factor 7 Sexual .13 .52 .08 -.09 -,16 -.36 -,01 Communication .30 -.22 .20 .25 -.23 -.02 Relatives 65 -.02 -.01 .11 -.16 -.09 -.15 Other man .13 .64 -.12 34 .17 9 .33 Other woman -.18 -.22 .26 .68 -.12 .09 .08 Housing -.18 .04 07 2 19 Children .36 ,16 .10 .12 38 -.13 Husband's absence …18 .15 .05 -.10 .64 Husband's drinking ,04 0 .07 .53 -.12 20 Husband's gambling .0 -.02 .00 .84 -.01 -.02 Husband's cruelty 5 .06 .79 -.08 -.1 . -.11 Wife's lack of interest -.1 .14 1 10 -.12 Husband's lack of interest 5 ,17 2 ,68 .0 -.04 Financial . -.06 15 -.01 -.10 Wife's ill health 14 15 2 .22 .01 -.58 Marital status .1 .10 -.05 ,88 -.08 Sex .08 3 .60 .07 -.22 -15 -.05 Accordingly,an exploratory factor analysis was Causes with Multiple Associations undertaken,with sex and marital status of respon- dent included as items.This gave a 7-factor solu When entries across the rows in Table 2 are tion (Table 4).The first factor appears to describe counted,husband's cruelty emerges as the cause a situation of general stress,involving housing showing the largest number of associations with and financial problems,conflicts with relatives, the structural variables.As well as being mainly disagreements over children,and lack of com- reported by women,it is associated with lower munication/common interests.The high loading SES,early marriage,short premarital acquain- of housing problems,a relatively infrequent com- tance,parental disapproval,husband's religion, plaint (see Table 1),suggests that housing com- early perception of the marriage breakdown,and plaints are good indicators of general marital change in living standards following separation. stress.The second factor centers on wife's lack of Overall,the picture presented is one of marriages interest in the marriage,sexual incompatibility, that were highly at risk from the beginning. and an "other man,''with lack of communication Although cruelty was self-defined by respondents also making a contribution.The third factor looks and,thus,covers a wide range of behaviors,these like a wife-abuse factor and is mainly reported by marriages do include cases of physical violence, women.The fourth factor describes the bored, including attempted murder. neglectful,unfaithful husband of a faithful wife. Four other causes are each associated with five The fifth factor describes the gambling/drinking structural variables.(a)Husband's drinking,also husband and is more commonly reported by mainly reported by wives,is associated with lower wives;it includes a negative loading on disagree- SES,early onset of breakdown,religion (Roman ments over children,which could have a number Catholic),and second marriages.Thus,there ap- of explanations including childlessness or the pears to be some overlap between this and the wife's view of the husband as totally lacking in- previous pattern;in fact,cruelty and drinking are terest in children.The sixth factor discriminates moderately correlated (r =.23).(b)Housing the divorced from the separated,replicates the complaints are associated with sex(female),early MANOVA finding that the divorced are some- marriage,parental disapproval,number of chil- what less likely to complain of sexual incom- dren,and improved living standards following patibility,and adds an association with husband's separation.Again,there appears to be some over- cruelty and (inversely)with his lack of interest in lap with the first pattern.(c)The "other man' the marriage.The final factor (like the second)is pattern is quite different.The complaint is gener- an "other man''factor,in this case associated ally made by husbands and is associated with a with the husband's absence and drinking and middling onset period,lower SES,and widow- negatively with wife's ill health (ill health was self- hood in the wife's parents'generation.(d)Sexual defined by respondents and included such condi- complaints are voiced more commonly by men. tions as "bad nerves').Correlation between the They are associated with religious affiliation in factors was negligible. men and with lack of such affiliation in women, August 1984 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY 559 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

TABLE 4. PERCEIVED CAUSES, MARITAL STATUS, AND SEX OF RESPONDENT. ROTATED FACTOR SOLUTION (PRINCIPAL COMPONENTS DQUART, NONORTHOGONAL ROTATION) Perceived Causes Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 Factor 5 Factor 6 Factor 7 Sexual .13 .52 .08 -.09 -.16 -.36 -.01 Communication .32 .30 -.22 .20 .25 -.23 -.02 Relatives .65 -.02 -.01 .11 -.16 -.09 -.15 Other man -.13 .64 -.12 -.34 -.17 .19 .33 Other woman -.18 -.22 .26 .68 -.12 .09 .08 Housing .77 -.18 -.04 -.14 .07 .27 .19 Children .36 .16 .10 .12 -.38 -.13 .21 Husband's absence .18 .06 .15 .42 .05 -.10 .64 Husband's drinking .04 .03 .39 -.07 .53 -.12 .29 Husband's gambling .07 .03 -.02 .00 .84 -.01 -.02 Husband's cruelty .15 .06 .79 -.08 -.14 -.05 -.11 Wife's lack of interest -.12 .80 .06 .14 .11 .10 -.12 Husband's lack of interest .05 .17 -.25 .68 .02 .06 -.04 Financial .59 .02 .16 -.06 .15 -.01 -.10 Wife's ill health .14 .15 .23 .22 .01 .01 -.58 Marital status .17 .14 .06 .10 -.05 .88 -.08 Sex .08 .03 -.69 -.07 -.22 -.15 -.05 Accordingly, an exploratory factor analysis was undertaken, with sex and marital status of respon- dent included as items. This gave a 7-factor solu- tion (Table 4). The first factor appears to describe a situation of general stress, involving housing and financial problems, conflicts with relatives, disagreements over children, and lack of com- munication/common interests. The high loading of housing problems, a relatively infrequent com- plaint (see Table 1), suggests that housing com- plaints are good indicators of general marital stress. The second factor centers on wife's lack of interest in the marriage, sexual incompatibility, and an "other man," with lack of communication also making a contribution. The third factor looks like a wife-abuse factor and is mainly reported by women. The fourth factor describes the bored, neglectful, unfaithful husband of a faithful wife. The fifth factor describes the gambling/drinking husband and is more commonly reported by wives; it includes a negative loading on disagree- ments over children, which could have a number of explanations including childlessness or the wife's view of the husband as totally lacking in- terest in children. The sixth factor discriminates the divorced from the separated, replicates the MANOVA finding that the divorced are some- what less likely to complain of sexual incom- patibility, and adds an association with husband's cruelty and (inversely) with his lack of interest in the marriage. The final factor (like the second) is an "other man" factor, in this case associated with the husband's absence and drinking and negatively with wife's ill health (ill health was self- defined by respondents and included such condi- tions as "bad nerves"). Correlation between the factors was negligible. Causes with Multiple Associations When entries across the rows in Table 2 are counted, husband's cruelty emerges as the cause showing the largest number of associations with the structural variables. As well as being mainly reported by women, it is associated with lower SES, early marriage, short premarital acquain- tance, parental disapproval, husband's religion, early perception of the marriage breakdown, and change in living standards following separation. Overall, the picture presented is one of marriages that were highly at risk from the beginning. Although cruelty was self-defined by respondents and, thus, covers a wide range of behaviors, these marriages do include cases of physical violence, including attempted murder. Four other causes are each associated with five structural variables. (a) Husband's drinking, also mainly reported by wives, is associated with lower SES, early onset of breakdown, religion (Roman Catholic), and second marriages. Thus, there ap- pears to be some overlap between this and the previous pattern; in fact, cruelty and drinking are moderately correlated (r = .23). (b) Housing complaints are associated with sex (female), early marriage, parental disapproval, number of chil- dren, and improved living standards following separation. Again, there appears to be some over- lap with the first pattern. (c) The "other man" pattern is quite different. The complaint is gener- ally made by husbands and is associated with a middling onset period, lower SES, and widow- hood in the wife's parents' generation. (d) Sexual complaints are voiced more commonly by men. They are associated with religious affiliation in men and with lack of such affiliation in women, August 1984 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY 559 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

and the complainants are likely to be separated good sense.It seems reasonable that a woman rather than divorced. who marries a man after a brief acquaintance These patterns among the most "popular" would be more likely to make a mistake and to causes show some relationship to the factors ob- find herself in a high-conflict and perhaps abusive tained in the factor analysis,but the fact that the or violent situation.Having done so,one also factor analysis included far fewer variables would expect her to recognize her mistake quick- naturally precludes the emergence of any close ly.A dramatic example was a well-educated associations.A further factor analysis including young woman,a computer programmer,who causes and structural variables gave a very large married a Pacific Islander she had met on a holi- number (22)of mainly one-or two-item factors; day.The courtship was swift and romantic;but therefore,this line of analysis was not pursued. once the two were married,cultural conflicts DISCUSSION quickly emerged,and the husband resorted to violence to try to make his recalcitrant new wife What interpretations can be made of these conform to his expectations of husbandly authori- manifold associations?A subset of the findings ty.In other,less exotic instances,wives describe perhaps can be best regarded as supporting and husbands as behaving attractively before marriage refining established knowledge.The sex dif- but"changing overnight'following the wedding. ferences in marital complaints parallel those It also seems reasonable that parental disap- reported by Levinger (1966)and Fulton (1979), proval should be particularly associated with the and the earlier dating of the breakdown by more obvious deficiencies of a prospective spouse, women is also in line with Fulton's findings.The like lack of money and an incompatible or dis- relationship between heavy drinking,violence, agreeable personality.In addition,since parents and lower SES is well known (Goode,1956),so are generally more tolerant of the marital choices that it comes as no surprise that wives of lower of their sons,in those cases in which parents SES men complain more of their drinking and strongly disapprove of their daughters-in-law one cruelty. might expect that they would become involved in Generally,early marriage is associated with less issues related to their grandchildren.This is education and lower incomes,and frequently with assuming,of course,that respondents'percep- early childbearing (Kitson and Raschke,1981),so tions of their parents'attitudes were accurate. that housing and financial problems are likely se- Some seemed to have clear evidence of these atti- quelae,as is the young husband's lack of time at tudes(My dad couldn't stand him;he wouldn't home and avoidance of family responsibilities. let him in the house"),but in other cases subse- The further link to conflict with relatives is a quent events may have colored these retrospec- logical one,since the housing problems described tions. by sample members included arrangements like The finding that wives who complained of moving in with in-laws,living in a caravan(trailer) housing and financial problems during marriage in the parents'backyard,and borrowing money were now enjoying higher standards of living also from relatives for rental bonds and payments. makes sense but needs a little more explanation. A major reason for seeking divorce is desire to These wives,although generally on low incomes, remarry,so that complaints of an "other were now exerting control over their own finances woman''naturally would be expected to be asso- and were likely to find this a great advantage.As ciated with divorce rather than separation.It is one woman remarked: worth noting,however,that there is no such link with an"other man"';in fact,the interview proto- Has my standard of living improved?My bloody cols show that women often preferred to avoid oath it has!I now own my own home which is legal ties in a second relationship: not flash but improving.I have my own vegeta- ble garden and chickens.The S2,200 debts he left I don't need the financial or religious security and two small children made it very difficult at that marriage offers;I prefer the loving,sharing, first,but I now have my own home.When we yet independent commitment I have with the were together we always lived in rented flats,and man I now share my life with money was always short. Irishmen have a reputation for frequenting The fact that the two-child family is least beset pubs,and most Australian-born Roman Catholics by housing and in-law problems is interesting in are of Irish origin:so that the association between the light of the further finding (Burns,1981)that religion and complaints of husband's drinking it is among families of this size that good relations and lack of time at home also fit into an estab- with the noncustodial parents are most likely to be lished picture (Calahan and Cisin,1976). maintained.Since the two-child family is current- Some other findings are more novel but make ly the norm,perhaps adherence to this norm be- 560 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon,19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

and the complainants are likely to be separated rather than divorced. These patterns among the most "popular" causes show some relationship to the factors ob- tained in the factor analysis, but the fact that the factor analysis included far fewer variables naturally precludes the emergence of any close associations. A further factor analysis including causes and structural variables gave a very large number (22) of mainly one- or two-item factors; therefore, this line of analysis was not pursued. DISCUSSION What interpretations can be made of these manifold associations? A subset of the findings perhaps can be best regarded as supporting and refining established knowledge. The sex dif- ferences in marital complaints parallel those reported by Levinger (1966) and Fulton (1979), and the earlier dating of the breakdown by women is also in line with Fulton's findings. The relationship between heavy drinking, violence, and lower SES is well known (Goode, 1956), so that it comes as no surprise that wives of lower SES men complain more of their drinking and cruelty. Generally, early marriage is associated with less education and lower incomes, and frequently with early childbearing (Kitson and Raschke, 1981), so that housing and financial problems are likely se- quelae, as is the young husband's lack of time at home and avoidance of family responsibilities. The further link to conflict with relatives is a logical one, since the housing problems described by sample members included arrangements like moving in with in-laws, living in a caravan (trailer) in the parents' backyard, and borrowing money from relatives for rental bonds and payments. A major reason for seeking divorce is desire to remarry, so that complaints of an "other woman" naturally would be expected to be asso- ciated with divorce rather than separation. It is worth noting, however, that there is no such link with an "other man"; in fact, the interview proto- cols show that women often preferred to avoid legal ties in a second relationship: I don't need the financial or religious security that marriage offers; I prefer the loving, sharing, yet independent commitment I have with the man I now share my life with. Irishmen have a reputation for frequenting pubs, and most Australian-born Roman Catholics are of Irish origin; so that the association between religion and complaints of husband's drinking and lack of time at home also fit into an estab- lished picture (Calahan and Cisin, 1976). Some other findings are more novel but make good sense. It seems reasonable that a woman who marries a man after a brief acquaintance would be more likely to make a mistake and to find herself in a high-conflict and perhaps abusive or violent situation. Having done so, one also would expect her to recognize her mistake quick- ly. A dramatic example was a well-educated young woman, a computer programmer, who married a Pacific Islander she had met on a holi- day. The courtship was swift and romantic; but once the two were married, cultural conflicts quickly emerged, and the husband resorted to violence to try to make his recalcitrant new wife conform to his expectations of husbandly authori- ty. In other, less exotic instances, wives describe husbands as behaving attractively before marriage but "changing overnight" following the wedding. It also seems reasonable that parental disap- proval should be particularly associated with the more obvious deficiencies of a prospective spouse, like lack of money and an incompatible or dis- agreeable personality. In addition, since parents are generally more tolerant of the marital choices of their sons, in those cases in which parents strongly disapprove of their daughters-in-law one might expect that they would become involved in issues related to their grandchildren. This is assuming, of course, that respondents' percep- tions of their parents' attitudes were accurate. Some seemed to have clear evidence of these atti- tudes ("My dad couldn't stand him; he wouldn't let him in the house"), but in other cases subse- quent events may have colored these retrospec- tions. The finding that wives who complained of housing and financial problems during marriage were now enjoying higher standards of living also makes sense but needs a little more explanation. These wives, although generally on low incomes, were now exerting control over their own finances and were likely to find this a great advantage. As one woman remarked: Has my standard of living improved? My bloody oath it has! I now own my own home which is not flash but improving. I have my own vegeta- ble garden and chickens. The $2,200 debts he left and two small children made it very difficult at first, but I now have my own home. When we were together we always lived in rented flats, and money was always short. The fact that the two-child family is least beset by housing and in-law problems is interesting in the light of the further finding (Burns, 1981) that it is among families of this size that good relations with the noncustodial parents are most likely to be maintained. Since the two-child family is current- ly the norm, perhaps adherence to this norm be- 560 JOURNAL OF MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY August 1984 This content downloaded from 211.80.94.134 on Mon, 19 Dec 2016 05:27:55 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms